For more on reforming the UN secretary-general selection process, click here to access EIA's interview with Yvonne Terlingen.

When on October 13, 2016, the General Assembly appointed by acclamation António Guterres of Portugal as the United Nations’ ninth secretary-general, there was a sense of excitement among the organization’s 193 members. For once, so it seemed, they felt they had played an important role not only in choosing the secretary-general but also in appointing a man generally considered to be an outstanding candidate for a position memorably described as “the most impossible job on this earth.”[1. Trygve Lie, the first UN secretary-general, greeting his successor, Dag Hammarskjöld of Sweden, at Idlewild Airport in New York on April 9, 1953.] The five permanent, veto-wielding members of the Security Council (Perm Five) still exercised the greatest power in the selection process, as they always had in the past. Yet the candidate chosen appears, surprisingly, not to have been the first choice of either the United States or Russia, two of the Perm Five that until then had effectively chosen the secretary-general between them in an opaque and outdated process. It is doubtful that António Guterres would have been appointed if the General Assembly had not embarked on a novel process to select him.

The method to select the UN secretary-general is laid down in a few words in the UN Charter. Article 97 allocates responsibility for appointing the secretary-general to all members of the General Assembly acting on the recommendation of the Security Council. However, for the last seventy years—with one circumstance-specific exception[2. Trygve Lie was reappointed by the General Assembly in 1950 without a recommendation from the Security Council, two of its members having consistently blocked his reappointment.]—the General Assembly has had no say in the selection: its member states merely rubber-stamped the decision of the Perm Five, which recommended just one candidate each time for the General Assembly to appoint. All previous secretaries-general were chosen on the basis of a haphazard and secretive process that occurred behind closed doors and was not merit based. The process was geared toward appointing the lowest common denominator candidate,[3. Brian Urquhart and Erskine Childers, “A World in Need of Leadership: Tomorrow’s United Nations,” Dag Hammarskjold Foundation (1990), p. 25. John Bolton, a former U.S. Permanent Representative to the UN, recalled that U.S. Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice told him during the then selection of a new secretary-general, “I am not sure we want a strong secretary-general.” See John Bolton, Surrender is Not an Option (New York: Threshold Editions, 2007) p. 279.] but nevertheless produced a few outstanding secretaries-general. There has never been a female secretary-general, and until 2016 only three women had ever made it on a Security Council shortlist.[4. Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit (India) in 1953, Gro Harlem Brundtland (Norway) in 1991, and Vaira Vike-Freiberga (Latvia) in 2006.] The entire process lacked transparency and accountability and fell far short of the UN’s own standards and ideals, let alone the current recruitment practices for top international positions.

Selections of all previous secretaries-general were made without appointment criteria, without a call for nominations or for CVs, without a timeline for nominations, and without public hearings or other effective methods of public scrutiny. In recent selections, candidates were often pushed into horse trading with the Security Council’s permanent members to gain their support in exchange for making promises of senior UN posts for their nationals. This has led to some countries holding monopolies over key posts.[5. For example, France effectively vetoed Kofi Annan’s appointment by casting negative votes many times in the Security Council in 1996 until he agreed that a French national be appointed to head the UN peacekeeping department.] Moreover, the tradition of appointment for a five-year, once-renewable term, with reappointment controlled by the Perm Five, has effectively secured a secretary-general beholden to the Council's most powerful members. The whole process “would be rejected as a bad joke by any serious institution in the private sector,” noted one senior UN authority who worked under multiple secretaries-general.[6. Brian Urquhart, “Selecting the World’s CEO,” Foreign Affairs 74, no. 3 (May/June 1995).]

Antonio Guterres awaits the swearing-in ceremony in the General Assembly Hall, December 12, 2016. Guterres was likely not the first choice of either the United States or Russia. Photo credit: United Nations Photo via Flickr

Antonio Guterres awaits the swearing-in ceremony in the General Assembly Hall, December 12, 2016. Guterres was likely not the first choice of either the United States or Russia. Photo credit: United Nations Photo via Flickr

Key Features of Historic Change

Yet over the last two and a half years the United Nations has forged dramatic change and created a much more open, transparent, and inclusive selection process, which has had an impact on the quality of the outcome[7. Several permanent representatives of missions at the United Nations told the author they believed that some (weaker) previous secretaries-general would never have been appointed had this new process been in place.] and, arguably, the standing of the United Nations as a whole. Prompted by intensive and persistent NGO lobbying, the General Assembly adopted the landmark Resolution 69/321 on September 11, 2015. For the first time, the Assembly agreed on a broad timeline for the selection process, to be initiated by a joint letter of the presidents of the Security Council and the General Assembly; on broad selection criteria;[8. These included a candidate who embodies the highest standards of efficiency, competence, and integrity and who possesses proven leadership and managerial abilities, extensive experience in international relations, and strong diplomatic, communication, and multilingual skills, as specified in General Assembly Res. 69/321, para. 39.] on publishing the names of all candidates; on calling for their CVs and mission statements; and on inviting states to present women as candidates. Crucially, the Assembly decided to have “informal dialogues” with candidates and gave the president of the General Assembly a mandate “to actively support this process.”

On December 15, 2015, a year before the end of Ban Ki-moon’s second term and following a three-month drafting process, the presidents of the Security Council (then held by the United States) and of the General Assembly (then held by a Danish national) sent their joint letter to start the process and to invite candidates, thereby putting the General Assembly on a stronger footing in the process. The president of the General Assembly opened a dedicated website and listed candidates promptly as they came forward with their CVs and vision statements, which all candidates submitted. In a historic first, the majority of candidates—seven out of thirteen—were women. Also unprecedented were the informal, open, webcasted hearings that the president of the Assembly organized for all candidates with all member states, where candidates were asked pointed questions about their vision, record, and plans in office. Also new was civil society participation in the hearings—albeit very limited—with questions selected from thousands submitted by the global public. The president even arranged for all candidates to answer questions from the UN press corps after the hearings, and invited them to attend three sets of high-level meetings in New York in the first half of 2016, thus levelling the playing field by giving lesser known candidates equal voice. More controversially, he arranged for a televised town hall–style meeting in July 2016 moderated by al-Jazeera in which all but two of the then nominees participated.[9. Srgjan Kerim (Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia) and Miroslav Lajčák (Slovakia).] In sum, there were much higher levels of public scrutiny and media interest and access than ever before.

Irina Bokova, a Bulgarian national, was the presumed frontrunner in early 2016. Photo Credit: Rama via Wikimedia Commons

Irina Bokova, a Bulgarian national, was the presumed frontrunner in early 2016. Photo Credit: Rama via Wikimedia Commons

All these changes were made in the face of strong opposition from permanent Security Council members Russia, China, and, to a lesser extent, the United States, all of which preferred sticking strictly to business as usual.[10. To underline their opposition, the Russian deputy permanent representative did not speak at the dialogues with candidates or in the private one-hour meetings that the Security Council offered all candidates. China was present at the General Assembly meetings and, although not speaking for itself, associated itself with questions put by the G77 group of countries. To their credit, the permanent representatives (or their deputies) of France, the United Kingdom, and the United States all took an active part in the meetings with candidates.] Just as remarkable as the change in the process was the outcome it produced: Although António Guterres had consistently led in all the informal Security Council polls—which included the views of the ten elected member states of the Security Council—he was known to stand up for his views and did not come from Eastern Europe, the region that had claimed it was “their turn” to produce a secretary-general, a claim repeatedly backed by Russia. However, while the process produced an excellent candidate, it obviously did not respond to the widespread calls for a woman to be given the UN’s top post, a signal that more gender work needs to be done.

U.S. Permanent Representative to the UN Samantha Power acknowledged the changed dynamics brought about by the new open and inclusive process and the influential role played by the General Assembly. In response to Guterres’s appointment, she remarked,

This year, at long last, the process evolved. For the first time, those vying for the job had to defend their visions for a more secure, just, and humane future in informal dialogues that the entire world could watch in real time. And these conversations mattered—there is no question that the General Assembly and other dialogues shaped perceptions, informing the Council and broader UN membership thinking from the outset.[1. Samantha Power, “Ambassador Power Remarks to the UN General Assembly on the Appointment of António Guterres as the Next Secretary-General of the United Nations,” October 13, 2016.]

So what happened? What were the factors and who were the actors behind the creation of this new, much more inclusive and open process? What more needs to be done? And is this changed process relevant for other UN and international high-level appointments of comparable importance that currently fail the test of transparency and inclusivity?

Why Did Change Happen?

A rare combination of factors was responsible for what occurred. First, the General Assembly had a huge appetite to change the selection process and put a more charismatic and visionary leader at the helm of the United Nations. Increasingly frustrated by the lack of membership reform to make the Security Council more representative of today’s world, and by the Council’s inability to tackle several major world crises, the Assembly welcomed a timely opportunity to assert its authority on the selection. The Assembly had for decades called for a more open and inclusive selection process,[12. See for example, General Assembly Resolutions 51/241 (1997), 60/286 (2006), 64/301 (2010), and 67/297 (2013).] but failed at implementation. When it had tried in the past, it had always been too late and the permanent two (or three) Council members had already made the choice between them. For example, in 2006, the year Kofi Annan was to leave office, Canada produced a proposal to improve the selection process in the body that is tasked with addressing this issue annually: the Ad Hoc Working Group on the revitalization of the work of the General Assembly (AHWG). At the same time, thirteen NGOs, at the initiative of the World Federalist Movement–Institute for Global Policy, started a campaign for an open and transparent process.[13. The thirteen founder NGOs of the 2006 campaign were: Amnesty International, Center of Concern, CIVICUS, Equality Now, FEMNET (African Women’s Development and Communication Network), Forum–Asia, Global Policy Forum, Committee for Nuclear Policy, Social Watch, Third World Network, UBUNTU–World Forum of Civil Society Networks, Women’s Environment and Development Organization, and the World Federalist Movement–Institute for Global Policy. All but the Center for Concern and UBUNTU joined the 1 for 7 Billion campaign.] Yet by the time the AHWG started serious discussions, the United States had already decided on Ban Ki-moon, and Moscow and Beijing (arguing for “Asia’s turn”) agreed shortly afterward. The Security Council recommended Mr. Ban on October 9, 2006, and the Assembly appointed him a few weeks later. Thus, on this most recent occasion, when prompted well ahead of time, the Assembly was more than ready to act, and nearly all its members—apart from the Perm Five—did so with enthusiasm.

Two groups emerged in the Assembly as the strongest advocates for an open, transparent, and inclusive process: the Accountability, Coherence, and Transparency (ACT) group of twenty-five states from all regions, with Estonia and Costa Rica providing strong leadership on this issue; and the 120 states that form the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM), coordinated by Algeria. An effort by the ACT group in the summer of 2014 to get the Assembly to agree on selection criteria did not gain political traction and ultimately failed. For many years the NAM had called for a stronger Assembly role in the selection, for more transparency and inclusivity, for a dialogue in the Assembly with all candidates, and for the Security Council to recommend multiple candidates to the Assembly. The combined strength of both ACT (which had just formulated a concrete plan of action for a more transparent, inclusive, and rigorous selection process) and NAM (which represented roughly two-thirds of the Assembly’s membership) provided a solid basis for reform, especially after both groups combined efforts in late 2014 with a new civil society campaign called “1 for 7 Billion: Find the Best UN Leader,” which had formed to achieve broadly similar objectives, as described below. These joint efforts by member states and civil society were crucial for achieving the changes incorporated in landmark Resolution 69/321 and other measures. In addition to Algeria for NAM and Estonia and Costa Rica for ACT, vocal supporters for reform in the Assembly included Brazil, Canada, Colombia, Finland, Guatemala, Luxembourg, Liechtenstein, Malaysia, Mexico, Sweden, and South Africa.

The Croatian co-chair of the AHWG played a crucial role in securing a successful outcome of both General Assembly Resolution 69/321 and its important successor Resolution 70/305, which opposed a monopoly on senior UN posts by any state or group of states. He skillfully laid the groundwork for negotiations that made it possible for the Perm Five to eventually join consensus on both resolutions.

Mogens Lykketoft, president of the 70th session of the UN General Assembly. Photo credit: United States Mission Geneva via Flickr

Mogens Lykketoft, president of the 70th session of the UN General Assembly. Photo credit: United States Mission Geneva via Flickr

A second important factor was the key role played by the proactive president of the 70th General Assembly, Mogens Lykketoft, a Danish former foreign minister and speaker of parliament. He fully exploited his mandate to act based on Resolution 69/321. Soon after his appointment, Lykketoft made it clear that “creating more transparency and openness when selecting the next secretary-general” was a priority. First, he helped ensure that the joint letter between the presidents of the Council and the Assembly to start the selection process was eventually sent in 2015. He also created the format for the hearings, decided they would be open through webcasting, and encouraged candidates to participate and come forward at an early date (those entering late did not fare well, a sign of the process’s impact).[14. The long-awaited entry of Kristalina Georgieva (European Commissioner for Budget and Human Resources)—which complicated matters because another Bulgarian national (Irina Bokova) was already in the race—only materialized on September 29, 2016, when the Security Council had already conducted most of its informal straw polls. UN observers felt her late candidacy hindered her chances of becoming secretary-general and probably hastened the selection of Mr. Guterres.] The president and his team facilitated maximum transparency of the General Assembly process, including two minutes of civil society interventions in coordination with the UN Non-Governmental Liaison Service in the middle of the two-hour-long “dialogues.” At the end of the historic meetings, the president made a helpful summary of the views expressed by member states about the sort of secretary-general they were looking for, well before the Security Council started its discussions.[15. At the closing of dialogues in the General Assembly, the president of the Assembly summarized the debates on June 7, 2016: “You are looking for a strong, independent, and courageous secretary-general who will make full use of the powers provided for in the UN Charter. You would most certainly welcome the first-ever female secretary-general and, more broadly, a person committed to ensuring that this organization promotes and embodies gender equality at all levels. And, finally, you are looking for a candidate who has the skills to transform this organization’s tools, capacity, and culture—so as to respond to today’s peace and security challenges, to drive forward implementation of the 2030 Agenda and the Paris Climate Agreement, to ensure greater respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms, and to give due priority to the world’s most vulnerable countries and peoples.” Looking back, that description fits the newly appointed secretary-general, apart from his not being a woman.]

Third, substantive change would not have happened without civil society acting as a catalyst to prompt the General Assembly to change the process well before the expiry of Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon’s term on December 31, 2016. NGOs had learned from past experience that timely action was key for change. As noted, in November 2014 the civil society group “1 for 7 Billion,”[16. The “1 for 7 Billion” campaign, www.1for7billion.org.] which has since grown to over 750 supporting NGOs and their affiliates worldwide, launched its campaign to reform the process. The group was founded on the premise that the secretary-general represents the aspirations of all people in the world and that an open and transparent selection process involving all member states and civil society would help produce the best candidate, revitalize the United Nations, and enhance the organization’s global authority. The group’s thirteen founding NGOs, including nearly all those that formed the 2006 campaign,[17. Eleven of the NGOs of the 2006 campaign (see endnote 13) were joined by the social campaigning organization AVAAZ and the World Federation of United Nations Associations.] signed an open letter to all heads of state, foreign ministers, and diplomats in New York calling for an achievable plan of action. The letter attracted considerable public interest.

Most of the group’s proposals[18. The proposals of 1 for 7 Billion included formal selection criteria, a call for nominations, a clear timetable and deadline for nominations, publication of an official list of candidates with their CVs and vision statements, and open hearings for candidates with all members of the General Assembly and with civil society participation. The campaign also argued for multiple candidates for the General Assembly to choose from, and for secretaries-general to serve a longer, single term—possibly of seven years—to enhance their independence. It opposed candidates having to make promises on senior UN posts in exchange for support. The campaign called especially for qualified female candidates, but also for the most highly qualified person to be appointed, regardless of gender or region. For the text of the 1 for 7 Billion Policy Platform, see www.1for7billion.org/s/1for7billion-policy-platform.pdf.] were achieved over the course of two years through intensive lobbying, principally in New York but also in major country capitals. In New York, 1 for 7 Billion engaged extensively with a wide range of member states representing all regions of the world, both in the General Assembly and in the Security Council before, during, and after key steps in the process. These included the adoption of the groundbreaking General Assembly Resolution 69/321 of September 2015, which created a more transparent process; Resolution 70/305 of September 2016, which addressed transparency in senior appointments; and Resolution 71/4 of October 2016, which appointed the new secretary-general.

The campaign provided diplomats with specific information and ideas prior to debates and during negotiations, pushed for the writing of a substantive joint letter by the presidents of the Assembly and the Council, and made suggestions for the format of dialogues with candidates in the General Assembly, including civil society participation. It also published an annotated platform showing how its proposals were based on existing UN resolutions and other authoritative UN and international sources.[19. For the text of the Commentary on the 1 for 7 Billion Policy Platform, see www.1for7billion.org/s/1for7billion-commentary-principles-and-recommendations.pdf/.] It produced charts comparing country positions on specific reform proposals (highlighting those who opposed) and on comparative appointment practices of executive heads in UN Headquarters, the International Labour Organization, the World Trade Organization, and the World Health Organization. The 1 for 7 Billion campaign also published background papers on the concept of a longer, single-term appointment and on the backroom deals and monopolies on senior posts held by some permanent Council members. The campaign interacted with three presidents of the General Assembly and their offices, and issued a range of press statements, reported key developments through social media, and organized public meetings at UN Headquarters together with supportive member states to brief the press and discuss and promote reform proposals. Presidents of the General Assembly and a range of member states publicly commended the contribution made by 1 for 7 Billion to improving the process.

The campaign stimulated debates worldwide about the characteristics of an outstanding secretary-general. Partner NGOs working at the national level in various regions also promoted debates, including those held at the global civil society meeting organized by CIVICUS in Colombia in April 2016. Another founding NGO, the United Nations Association of the United Kingdom, promoted in-depth parliamentary debates that had a positive impact on the government’s position; organized opinion polls among NGO supporters about the type of secretary-general they wanted; and organized, with NGO partners, three parallel public debates for more in-depth discussions with several candidates together on one platform. Further, 1 for 7 Billion encouraged debates in a range of parliaments by working with Parliamentarians for Global Action and the Inter-Parliamentary Union.

Crucial support for reform proposals came early on from The Elders, an independent group of global leaders founded by Nelson Mandela in 2007. Writing in the New York Times on February 6, 2015, Kofi Annan, chair of The Elders and himself a former secretary-general, and Gro Harlem Brundtland, former prime minister of Norway, urged an immediate overhaul of the selection process, called for a thorough and open search for the best qualified candidates irrespective of gender or region, and echoed key reform proposals made by 1 for 7 Billion. The Elders continued to champion reform in pointed public statements and in successive public debates at the United Nations with supportive member states and civil society groups. At one such debate Mary Robinson, a former president of Ireland and UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, said that maintaining the status quo was “not just unwise, but morally inexcusable,” and she condemned the practice of horse trading for senior posts in exchange for Perm Five support as an “unseemly practice that seriously undermines the reputation and effectiveness of the United Nations.”

Women’s groups were particularly active in promoting change. After eight male secretaries-general, many felt it was high time to select a woman for the position. The Campaign to Elect a Woman UN Secretary-General attracted wide support, rolling out the names of highly qualified women from all regions and promoting transparency in the process. At the General Assembly, Colombia formed the Group of Friends to Elect a Woman Secretary-General, which attracted the support of sixty states from all regions. The group promoted the prospect of a female secretary-general (surprisingly, the highest placed female candidate ranked only fourth in the final Security Council poll of ten) and highlighted the need for gender equality at all levels of the UN structure, which is now a top priority for the organization and its new secretary-general.

Transparency and the Security Council

The much more open and transparent process in the Assembly put pressure on the Security Council to step up to the mark when it reached the stage of selecting a candidate to recommend to the Assembly in late July 2016. New Zealand had already taken the initiative in July 2015 to raise the selection process in the Council, and Malaysia had included the topic in its “wrap up” the previous month. The United Kingdom pressed for early nominations with a clear deadline in the proposed joint letter, but failed to get support from the other Perm Five. The ten elected Security Council members (each for a two-year term) were more active than in previous selections, with Chile, Malaysia, New Zealand, and Spain calling for more openness and transparency, a call also backed by the United Kingdom. Some elected members, including Spain, argued that the veto should not apply in the straw polls for the selection. For the first time in UN history the Security Council met privately, for one hour, with all candidates who requested to do so. However, the Council members never sat together afterward or at other meetings to assess the candidates against the criteria that the Assembly had specified.

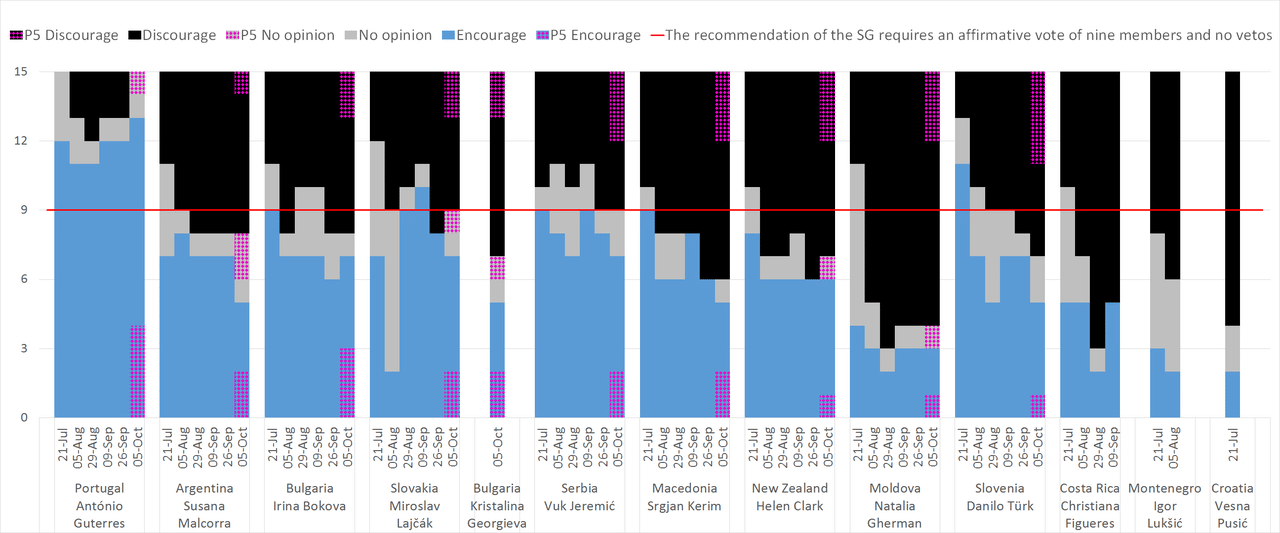

In preparation for a formal vote, the Council held its first straw poll in a closed session on July 21, 2016, in which members could “encourage,” “discourage,” or express “no opinion” about a candidate.[20. For a lucid explanation of the Council’s polling practice and a concise historical background, see Security Council Report, Special Research Report: Appointing the UN Secretary-General: The Challenge for the Security Council, June 30, 2016, www.securitycouncilreport.org/special-research-report/appointing-the-un-secretary-general-the-challenge-for-the-security-council.php.] António Guterres was the only candidate to receive more than the required nine positive votes and to get no “discourage” votes from a veto-carrying member, all of which could have resulted in his immediate recommendation by the Council if the vote had been formal. However, four more straw polls were held, all without color coding, meaning that the outcome did not show how permanent members voted. When the first “color coded” vote was held on October 5, Mr. Guterres, who had led the polls throughout, topped the polls again with thirteen positive votes, two votes of “no opinion,” and none against. Without any permanent member casting a veto, his recommendation for appointment was promptly announced by the Russian president of the Council in the presence of his fourteen colleagues. All poll results, which were intended to be kept secret, were leaked within about thirty minutes of voting—even before some of the candidates themselves had been informed by their governments. The failure to officially disclose the poll results harmed the standing of the Council and stood in sharp contrast to the openness displayed in the General Assembly. Security Council members, who initially favored keeping poll results secret, changed their minds in the course of voting. In the end, Russia was allegedly the sole country to oppose publishing the outcome of the polls.

UN Secretary General selection straw polls, July 21 through October 5, 2016. Photo credit: Ivoluissantos via Creative Commons

UN Secretary General selection straw polls, July 21 through October 5, 2016. Photo credit: Ivoluissantos via Creative Commons

Assessment of the New Process

The more open and transparent process created in Resolution 69/321—notably the open and webcasted meetings with all candidates in the General Assembly—clearly had an impact on the permanent members of the Security Council, which still control the appointment through their veto power. Although the new process does not ensure that the most highly qualified candidate will be appointed, it has made it much more difficult for the Council to recommend a weak candidate or to veto an outstanding candidate like António Guterres. The General Assembly, whose authority has been considerably enhanced in the new selection process, will not stand for it. The time of rubber-stamping is over.

There are other important outcomes. By appearing in so many different forums, candidates were tested on a much wider variety of skills and qualities than ever before. Going through this competitive process also enhanced the authority of the newly appointed secretary-general. With the appointment of a former top UN official (Guterres had been the UN High Commissioner for Refugees from 2005 to 2015) and former prime minister, the new process set a higher standard for future office holders. Although the majority of candidates this time were women, they did not perform as well in the polls as expected, despite high qualifications. If the next secretary-general is to be a woman, as many argue it should be, the search for outstanding female candidates from various regions will have to start early on.

The outcome also shows that claims to regional rotation of the post have lost much of their force for future selections. This time around there were more candidates than ever before, and they came from several regions of the world. Despite the Eastern European claim to the post, publicly backed by Russia until the day before the Security Council’s decision, a Western European candidate was chosen. Nonetheless, regional balance will likely play a role in future choices between equally qualified candidates or in the interest of reflecting a North–South balance between the secretary-general and his or her deputy. Last, it has become virtually impossible for a permanent member to bring in a “dark horse candidate” at the last minute. Candidates have learned the lesson that a timely entry and participation in the full process are essential to winning support for an appointment.

Looking Ahead

The unsettled proposal for a longer, single term of appointment, which would enhance the independence of the secretary-general, has attracted increasing attention among diplomats in New York, although not yet in country capitals. Equally, the NAM-backed proposal for the General Assembly to be able to choose from among multiple candidates is yet to be decided. Both require further in-depth discussion. Looking back at the dialogues with candidates, it is clear that they had too little time to answer the detailed and often repetitive questions they received from delegates. Member states would do well to streamline the process and coordinate questions. The hearings could be slightly longer, the questions could be shorter and some asked in writing beforehand, and civil society questions could be interspersed and given additional time.

Looking ahead, the General Assembly will have to decide how the new process, involving a range of public meetings and debates, applies to a sitting secretary-general with a heavy schedule (an issue that would be eliminated by enacting a longer, single term). Member states will also have to provide clarity on the process for nominating candidates (now implied to require nomination by government), and confirm that countries can nominate nationals of other countries or noncitizens. The Assembly may want to consider forming a search committee, possibly of senior independent experts, to help identify outstanding candidates. The question of who can withdraw a candidacy (a nominating government, a candidate, or both) must also be addressed, as this became controversial when Bulgaria nominated two candidates at different times last year. Further improvements would include setting an end date for nominations, agreeing to a process for shortlisting, and the drafting of a code of ethics for the selection, similar to the one adopted by the World Health Assembly in May 2013.[21. World Health Assembly, “Follow-Up of the Report of the Working Group on the Election of the Director-General of the World Health Organization,” May 27, 2013, document WHA66.18 in WHA66/2013/REC/1, p. 34.] This could help level the playing field for candidates and provide guidance on potential conflicts of interest that were raised in the latest round.[22. Some member states, including those with a candidate, identified problems with candidates running for secretary-general while continuing to hold a senior UN or comparable international position. They and others raised concerns about the ability of such candidates to satisfactorily carry out their duties while running for the secretary-general’s position or feared that such candidates took advantage of their position to gain access for lobbying that was not available to others. (Two candidates kept their senior UN position throughout the race, whereas a senior EU official suspended her work on declaring her candidacy). Questions also arose about campaign financing and government funding.] Finally, the Security Council should consider publishing the outcome of all future polls. This would reinforce the authority of the Council in the process, protect the dignity of the candidates, and fulfill the expectations of a transparent selection process.

The more open, transparent, and inclusive process adopted for selecting the UN secretary-general is not only highly relevant for all senior and other UN appointments but also for its specialized agencies, notably the Bretton Woods institutions. The World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) have come under increased criticism for failing to allow merit-based appointments for the president of the Bank and the managing director of the Fund by restricting appointees to a nationality or region. Thanks to a long-standing informal arrangement between the United States and Europe, a U.S. national traditionally holds the presidency of the World Bank (currently President Jim Yong Kim, appointed in 2012 and reelected in 2016 as the sole candidate), and a European holds the managing directorship of the IMF (currently held by French national Christine Lagarde, appointed in 2011 and reappointed in 2016, both times as the sole candidate). These American and European nationals have traditionally been appointed by consensus in a weighted voting system. A lack of meritocracy means that top candidates from most of the world’s regions are effectively excluded from serious consideration and appointment.

In 2011 the governors of the World Bank committed themselves to an “open, merit-based, and transparent” process to select its president. Executive directors of the IMF did the same in 2005, endorsing key principles for the selection of its managing director that included an open and transparent process. Although both the Bank and the Fund have made efforts to reform their processes by drafting broad selection criteria and considering multiple candidates—with the Bank setting short deadlines for nominations, open to all member countries[23. World Bank, “World Bank Board Launches Presidential Selection Process,” August 23, 2016.]—it is far from clear whether and how these principles have been translated into practice in a process that remains closed and opaque. Critics have argued against backroom deals, called for an end to monopolies, and sought an open and competitive process of selection that includes a “transparent interview and selection process.”[24. Shawn Donnan, “World Bank Staff Challenge Jim Yong Kim’s Second Term,” Financial Times, August 9, 2016; “Lucky Jim,” Economist, September 15, 2016.]

If the Bank and the Fund wish to implement the principles to which they are committed, they should adopt a meritocratic, inclusive, and transparent selection process that is open to the best candidates from all over the world. As a starting point they may be well served by looking at what the United Nations has done to create a very different process to select its secretary-general.

A PDF version of this essay is available to subscribers. Click here for access.

More in this issue

Summer 2017 (31.2) • Review

Rethinking the New World Order by Georg Sørensen

This book provides an elegant account of the nature and inherent tensions in global order. By engaging with ongoing theoretical debates between liberal optimists and ...

Summer 2017 (31.2) • Feature

Legitimate Authority and the Ethics of War: A Map of the Terrain

In this article, Jonathan Parry challenges both the traditional conception of the legitimate authority criterion as well as those reductivists who reject it wholesale. Specifically, ...

Summer 2017 (31.2) • Review

Preventive Force: Drones, Targeted Killing, and the Transformation of Contemporary Warfare, Kerstin Fisk and Jennifer M. Ramos, eds.

This collection of eleven original articles presents a wide variety of perspectives on what the moral and legal framework for preventive use of force by ...