The first thing you notice is the darkness. Monrovia, Liberia’s capital, is an hour from the airstrip, and other than the occasional dimly lit chop-hut serving rice and fish, the way into the city is obscure. One is almost tempted to idealize this perfect darkness and its accompanying quiet as pristine elemental beauty, rather than what it really is: the wreckage of a disaster whose depths, as Ryszard Kapuściński writes, “condemned some to death and transformed others into monsters.” [1. Ryszard Kapuscinski, The Shadow of the Sun (New York: Vintage International, 2001), p. 255.]

Before its fifteen-year civil war started in 1989, Liberia generated 400 megawatts of electricity. Now, fully a decade after the United Nations Mission in Liberia finally intervened in the ethnic and resource conflict—a war that killed a quarter of a million people, the per capita equivalent of twenty million in the United States—there is still no grid whatsoever. Monrovia is a beleaguered city of more than one million residents, with many living as permanent refugees, trying to survive on just 25 megawatts of diesel-generated power, barely enough to support 1 percent of the population. As a country, Liberia uses less electricity in one year than an American football stadium consumes in a season. [2. Paul Farmer, “Diary,” London Review of Books 36, no. 20 (2014), pp. 38–39, www.lrb.co.uk/v36/n20/paul-farmer/diary.]

The primitive generators, to which only the wealthy and expatriates have reliable access, are constantly breaking and expectorating poisonous exhaust, turning the exteriors of buildings coal black. The grinding of these machines competes with the sound of air conditioners, indispensable in buildings that are sealed shut from the pollution; and amid all the noise it is difficult to rest at night, resulting in a semi-permanent feeling of fatigue.

Everything the manifold warring factions could carry, they took away. Metal and machinery from the mines, pipes and cables from the ports, wiring and tracks from the rail stations—all were stripped for export to finance Liberian warlords and multilateral forces alike. In 1994 the Nigerian-led peacekeeping operation, whose acronym, ECOMOG, was parodied as “Every Car Or Moving Object Gone,” captured and dismantled the port of Buchanan, exporting its industrial equipment to international second-hand plant and scrap metal markets for an estimated $50 million. [3. Stephen Ellis, The Mask of Anarchy: The Destruction of Liberia and the Religious Dimension of an African Civil War (New York: NYU Press, 2006), p.173.]

Until the plunder of Buchanan, Charles Taylor’s shadow state, called Greater Liberia, used this port to trade timber, rubber, gold, and, especially important, rich iron ore, which alone provided 25 percent of gross domestic product (GDP) before the war. International business partners benefited from bureaucracy-free deals negotiated directly with Taylor’s militia, the National Patriotic Front of Liberia, escalating Taylor’s annual personal profit, excluding his cannabis cartel, to as much as $100 million. [4. Ibid., p. 90.]

The destruction of the port arrested this industrial activity, which is when the manual mining of precious minerals—needing no infrastructure and only a pants pocket for export—became essential to the warlord economy. These “conflict diamonds” (not only from Liberia but also originating in Angola and Sierra Leone, among other countries) caught the world’s imagination, resulting in an international campaign—the Kimberley Process Certification Scheme—to prevent the rough stones from entering the marketplace. Liberia was then subject to trade sanctions enforced by the UN Security Council.

But as much as these reforms of the global diamond industry helped block one avenue of funding for armed conflict, they overlooked at least two critical factors in Liberia. First, conflict diamonds were a symptom of the industrial vandalism that had devastated the country’s economy; verifying the peaceful origins of rough diamonds does not necessarily aid the reconstruction of national infrastructure. The minimal support provided for reconstruction by “conflict-free” minerals is, in part, due to the second factor: that Liberia is not especially rich in precious minerals. During the war, diamond revenue came mostly from stones mined in neighboring Sierra Leone and Côte d’Ivoire, not Liberia, and the country is currently among the world’s smallest precious minerals producers. [5. Steven Van Bockstael, “The Persistence of Informality: Perspectives on the Future of Artisanal Mining in Liberia,” Futures 62, Part A (2014).] aa

Already too late

It was late June 2014, the rainy season, when I arrived. For six months the deluge is so fierce that when seated under a metal roof, as is often the case, you might have to shout to be heard by the person beside you. During this period crime escalates because guards cannot detect unusual sounds, and the hinterlands are cut off from the national economy, forcing, for example, gold miners in the southwestern greenbelt to carry ore across the border with Côte d’Ivoire rather than direct their traffic to Monrovia.

The agency driver and I were listening to the radio as we exited the airport, passing children walking single file through the darkness on the side of the road. That was the night Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) declared Ebola “out of control,” after the virus had entered the crowded city from the rural villages. “A scam,” the driver remarked confidently, responding to the dispatch on the radio. At that moment, when there were still fewer than thirty deaths in Liberia, calling the virus “out of control” seemed oddly disproportionate,[6. See, for example, the UNICEF SitRep#28 on Ebola in Liberia, dated June 25, 2014, crofsblogs.typepad.com/h5n1/2014/06/ebola-in-liberia-unicef-sitrep-28-june-25.html.] but he was also echoing a suspicion, shared by many in the country, that Ebola was only a new way for the government to extort money from the very international organizations for which I work. The theory is not far-fetched, given the history of factions committing “aid-attractive” atrocities to bring donations to their sides.[7. Linda Polman, The Crisis Caravan: What’s Wrong with Humanitarian Aid? (New York: Picador, 2011).] It is also, though, a symptom of living in a place where no one trusts anyone. More than 60 percent of children during the war—young adults in the country today—witnessed torture, murder, or rape; over 75 percent lost at least one family member. [8. Ellis, The Mask of Anarchy, p.146.] Speak with almost anyone who was in the country then and they are likely to describe beheadings, mass killings, or a traumatic escape from death.

I had come to Monrovia to work as a minerals advisor to the government. In 2007 Liberia entered the Kimberley Process, exchanging a trade ban on diamonds for assuming the burden of proving the peaceful origins of every stone exported from the country. The mineralized interior of Liberia hosts West Africa’s largest remaining tropical forest, a jungle whose “innocence” and “virginity” the British novelist and travel writer Graham Greene praised in the closing passage of his 1936 travelogue, Journey Without Maps, as “the graves not opened yet for gold, the mine not broken with sledges.”[9. Graham Greene, Journey Without Maps (London: William Heinemann Ltd, 1936).] Tragically, the retreat of the war economy to the interior—where warlords commanded children, farmers, and others as forced laborers—also acted like a geological exploration program, leading to the discovery of new deposits for which foreign investors are currently competing.

In a 1997 survey conducted by the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, 56 percent of child combatants said that after the war they wanted to go to school, 28 percent to learn a trade, and 6 percent wished to be farmers.[10. Ellis, The Mask of Anarchy, p. 132.] Instead, 70 percent of these ex-combatants are today working as manual diggers in gold and diamond mines.[11. United States Agency for International Development (PRADD Project, Liberia), “A Review of the Legal, Regulatory and Policy Framework Governing Artisanal Diamond Mining in Liberia,” November 2011, p. 2.] Despite the large, low-wage labor force and the flood of international investors, annual public revenue from mostly clandestine gold and diamond mining hardly exceeds $1 million, contributing little value to national reconstruction.[12. Republic of Liberia Office of Precious Minerals, Annual Report, 2013.]

On a rare sunny day I climbed the city’s highest hill to the ruins of the Ducor Hotel, whose winding staircases and rooftop nightclub suggest a former decadence. The hotel was a military headquarters during the war, changing hands several times before finally becoming a squatters’ residence. Now, nothing is left but concrete walls stripped of all their metal wiring and marked by holes chiseled for sentries to point guns down at the city streets. (“Bodies,” somebody had told me when I’d asked what these streets were like during the war. “Bodies everywhere.”) I watched from the hotel roof as a fisherman struggled in the shallow waters near the port. Fleeing the city in any small boat would mean almost certain death: the current is so ferocious it rips the polish from the toes of women standing ankle deep in the surf. Official refugee options offer little better hope. China and the United States are the only non-African countries even issuing visas in Monrovia; to travel anywhere else outside Africa, Liberians must first make their way to Accra, Ghana.

View of Monrovia from the Ducor Hotel. Courtesy of the author.

View of Monrovia from the Ducor Hotel. Courtesy of the author.

The previous evening I met a despairing health expert doggedly working on Ebola. MSF, she told me, was preparing to dispatch an epidemiologist to Liberia. I was certain I misunderstood. “No, you heard me correctly,” she said. “The epicenter right now is Guinea. MSF is overstretched. Nobody else is helping. All they can offer is one epidemiologist.” Her gaze fell to the ground and suddenly she looked much older than at the beginning of the evening. “The moment to act was in March when the virus was detected,” she lamented. “It’s already too late.”

It was neither the inaction that startled me nor even the lack of coordination among the dozens of aid agencies in the region. It was how inexpensive the intervention could have been. At that time, the estimated funding gap to contain Ebola in Liberia was just a million dollars, yet no private philanthropist, public aid agency, or company volunteered to provide this relatively small sum. Even if the funding estimate had been twenty times as large, the trauma, suffering, and death gripping West Africa was preventable—as was the disbursement of billions of dollars and the deployment of thousands of soldiers now required to avert a global pandemic.

The Delphic Oracles of Officialdom

Each year the UN Development Programme (UNDP) issues its scorecard of national well-being, the Human Development Index. In 2013 Liberia ranked 175 out of the 187 participating countries. Some 95 percent of Liberians live on less than two dollars per day[13. Republic of Liberia, “Agenda For Transformation: Steps Toward Liberia Rising 2030,” p. 13, http://mof.gov.lr/doc/AfT%20document-%20April%2015,%202013.pdf.]—not enough to meet basic daily needs, much less manage shocks and crises. When you are in Liberia, though, there are two ways to avoid fully experiencing its misery.

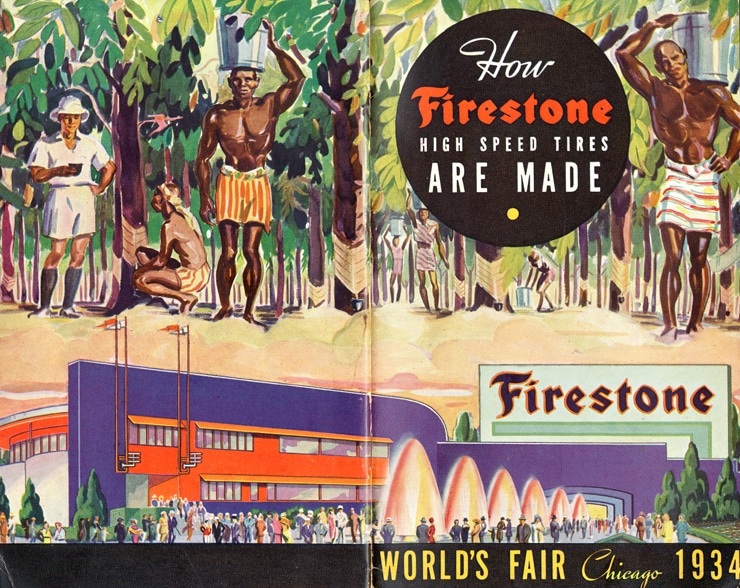

One is to be a resource profiteer. “Quite outside this strained, dreary and yet kindly life, at the end of several hours’ rough driving from Monrovia, live the Firestone men in the houses containing shower baths and running water and electric light,” wrote Greene in 1936, calling the Firestone company’s one-million acre concession “an impediment to any form of development.” In addition to the compound’s electricity and running water, Greene noted its wireless station, tennis courts, swimming pool, and “a new neat hospital.”[14. Greene, Journey Without Maps, p. 230.] To this day, the only reliable hospital in the country is at the Firestone plantation.

From the Firestone Factory and Exhibition Building, World's Fair, Chicago, 1934.

From the Firestone Factory and Exhibition Building, World's Fair, Chicago, 1934.

A second way that one can maintain the sense of well-being in Liberia is to inhabit the world of international officialdom by joining the stream of development consultants working on “projects”—experts who shuttle from luxury hotels to air-conditioned offices to seedy bars, their laptops blazing, all poised to publish the next pamphlet or doctrine to set post-conflict reconstruction and economic development, finally, on their proper course. And this in spite of a recent World Bank study—an assessment, as it were, of its own assessments—revealing that 35 percent of its papers, proposals, counterproposals, records, and reports are never downloaded, much less read.[15. Doerte Doemeland and James Trevino, “Which World Bank Reports Are Widely Read?,” Policy Research Working Paper, no. WPS 6851 (Washington, D.C.: World Bank Group, 2014), documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/2014/05/19456376/world-bank-reports-widely-read-world-bank-reports-widely-read.] This pestilence of paper has plagued internationalism from its inception. Over the nine weeks of the UN’s founding conference in San Francisco, participants consumed seventy-eight tons—a half-million sheets—of paper per day,[16. Stephen C. Schlesinger, Act of Creation: The Founding of the United Nations (Cambridge, Mass.: Westview Press, 2003), p. 122.] propelling a fetish that led Canada’s Lester Pearson, an early leader of the United Nations, to describe that organization in 1970 as “drowning in its own words and suffocating in its own documents.”[17. Shirley Hazzard, Defeat of an Ideal: A Study of the Self-Destruction of the United Nations (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1973), p.190; Hazzard is citing Pearson’s May 26, 1970 article in the New York Times.]

By definition, international development projects have narrow objectives, short lives, and are not institutionalized. “Even though we know better,” Harlan Cleveland said half a century ago, “we are still tackling twenty-year problems with five-year plans based on two-year personnel working with one-year appropriations.”[18. Hugh Keenleyside, International Aid: A Summary, With Special Reference to the Programmes of the United Nations (New York: James H. Heineman, 1966), p. 305; Keenleyside is referring to Cleveland’s November 14, 1964 address to the AFL-CIO.] All too frequently projects are also determined less by what countries need than by the particular interests of agencies or philanthropies. In 2006, to cite a glaring example, I consulted for a project whose mission of reducing exposure to toxic pollutants in Kadoma, Zimbabwe—admirable in most circumstances—overlooked the fact that 75 percent of people in the region were HIV-positive.

For heads of state, celebrity activists, and heralded intellectuals—the agenda setters whose Powerpoints prescribe the policy goals—the distance from reality is even more profound than for low-level consultants like me. For these notables, new hotels and traffic lights are constructed in anticipation of their visits, creating an illusion of progress. To be part of this consulting class is to have what the writer Primo Levi, in his vocation as a chemist, called “ideal work,” where “all you have to do is take off your smock, put on your tie, listen in attentive silence to the problem, and then you’ll feel like the Delphic oracle.”[19. Primo Levi, The Periodic Table (New York: Knopf, 1995), p. 182.]

International Aid: From “Technical Assistance” to “Reverse Assistance”

One common version of modern internationalism traces the history of cooperation through the progressive codification of matters of war and peace. According to this narrative, the story begins, say, with the creation of the laws of war in 1864, is followed by the Hague Peace Conferences of 1899 and 1907 dealing with the treatment of civilians and neutrals, then moves onward to the Treaty of Versailles and the founding of the League of Nations at the end of World War I.[20. Paul Kennedy, The Parliament of Man: The Past, Present, and Future of the United Nations (New York: Random House, 2006), pp. 5–10.] But internationalism also has more mundane administrative origins. The habit of calling intergovernmental conferences as we know them began in the 1850s, laying a foundation for global cooperation based on technical functions of public international unions, such as the International Telegraph Union, Universal Postal Union, and International Office of Public Health. Starting in the middle of the nineteenth century, the number of international conferences grew from nine to more than a thousand by World War I.[21. Keenleyside, International Aid: A Summary, p. 97; Keenleyside is referring to the 1928 book by C. Howard-Ellis, Origin, Structure and Working of the League of Nations.]

The enterprise we now call “international development” emerged from this essentially technical tradition as a vision of furnishing scientific advice to governments—“technical assistance”—to share the benefits of industrialism. In popular imagination, the United Nations exists primarily as a security organization, but the nexus of technical assistance and peace was built into its charter at the founding conference in San Francisco with the creation of the Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC). Gradually, the mission of ECOSOC—to improve international living standards as a means of reducing the threat of war—expanded to include issues of population, migration, famine, environment, and economic development, until by the end of the cold war approximately 90 percent of UN resources were dedicated to addressing these issues through the organization’s so-called specialized agencies.[22. Stephen C. Schlesinger, Act of Creation, p. 241.]

[embed]https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=U3cGnbCEb-w[/embed]

In 1950 the UN Secretariat executed its first technical assistance mission, sending a research team to examine the ailing tin mines of Bolivia. To lead it, Secretary-General Trygve Lie selected Canada’s Deputy Minister of Mines, the historian Dr. Hugh Keenleyside. Shortly after the Bolivia mission, Keenleyside was appointed director-general of the new Technical Assistance Administration (TAA), an institutional ancestor of today’s UNDP, which was created to stimulate industrialization in developing countries. To Keenleyside, technical assistance was not merely a matter of transferring technology from one place to another. It represented the “finest and highest of public concepts—an emerging universal acceptance of a philosophy of general responsibility for the welfare of all peoples.”[23. Hugh L. Keenleyside, Memoirs of Hugh L. Keenleyside, Volume 2: On the Bridge of Time (Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1982), p. 358.] Central to the realization of this philosophy was a coordinated vision of global development.

Along with other postwar internationalists, Keenleyside anticipated that large-scale funding for technical assistance would flow from U.S. President Harry Truman’s “Point Four” pledge, issued as the fourth point of his 1949 inaugural address, to make “the benefits of our scientific advances and industrial progress available for the improvement and growth of underdeveloped areas.”[24. See www.bartleby.com/124/pres53.html.] When congressional opposition to Truman’s support for what were labeled “give-away” international assistance programs ended hope for stable Point Four financing, technical assistance cum development devolved into a hodgepodge of competing fiefs that an increasingly disappointed Keenleyside dubbed the “cult of bankable projects.”[25. Keenleyside, Memoirs of Hugh L. Keenleyside, Volume 2, pp. 353–59.]

The postwar years were a period of bureaucratic proliferation. Moreover, by expanding its own version of technical assistance, the UN Secretariat in New York began a territorial war with European specialized agencies that remained from the defunct League of Nations and were already doing similar work.[26. Keenleyside, International Aid: A Summary, p. 207.] For Keenleyside, the purpose of the new international organizations, like his own TAA, was to support a peaceful vision of houses rising up, roads spreading out, and machines being put to work by offering scientific and engineering expertise to countries that were beginning to develop industrially. Technical assistance “projects” were conceived as “parts of a general scheme” for social and material progress, not as the “random improvement of technical skills” and a “haphazard set of unrelated projects.”[27. Ibid., pp. 162–64.]

Instead of this idealistic vision, international agencies became the primary beneficiaries of donor support, a form of “reverse assistance” resulting in as much as 75 percent of funds intended for developing countries being spent in the country where the money originated.[28. Keenleyside, Memoirs of Hugh L. Keenleyside, Volume 2, p. 476.] To justify their existence, the agencies—each urging its particular line of progress—lobbied national governments in Africa, Asia, and Latin America in hopes of increasing their volume of requests from these same states. This, in turn, created incentives for those governments to match their needs to the specializations of the agencies.[29. Hazzard, Defeat of an Ideal, p.190; Hazzard is citing Sir Robert Jackson, who in 1969 wrote A Study of the Capacity of the UN Development System (UN document DP/5; Geneva: United Nations, 1969), a report Hazzard called “the most thoughtful document ever to come out of the UN.”] “It violated the basic principle of aid,” Keenleyside writes in his 1966 book, International Aid. “The agencies were not always right. And psychologically the result was often detrimental as the attitude of the governments was adversely affected by the constant insistence on the superiority of agency opinions.”[30. Keenleyside, International Aid: A Summary, p. 163.]

Keenleyside’s disillusion was not restricted to the institutional narcissism of development agencies, but extended to the paternalism of its officers—the kind of experts the Viennese writer Stefan Zweig called the “bureaucratic aristocracy.” A proper expert “on mission” (as it is called when someone is sent abroad to work in “the field”), Keenleyside argued, was more generalist than technocrat, more humanist than social scientist, someone with broad interests who could make a mesh of many disparate things, and who possessed a bit of the missionary spirit. “Any suggestion of impatience,” Keenleyside cautioned, “any indication of a feeling of racial, social, or intellectual superiority, or any assumption of personal authority on the part of the UN adviser, could be instantly fatal to the success of his mission.”[31. Ibid., p. 219.]

This idealism feels anachronistic in today’s technocentric policy universe, but Keenleyside was hardly alone. Others, like C. W. Jenks, a director-general of the International Labour Organization in the early 1970s, described the essential qualities of international civil servants as integrity, conviction, courage, imagination, drive, and technical grasp—“in that order.”[32. Hazzard, Defeat of an Ideal, p.132.] And in her neglected yet brilliant 1973 critique of the United Nations, Defeat of an Ideal, Shirley Hazzard, a longtime staffer for Keenleyside prior to her breakthrough as a novelist, excoriated the “mesmerizing effect of official life . . . elites talking to themselves, their jargon just evasion.” As she writes: “An action that would run counter to what the establishment of the moment insists upon becomes a psychological—almost a physiological—impossibility. The bureaucratic addiction, with its vitiation of character and proportion, is insidious, and its power is only felt to the full under the challenge of withdrawal.”[33. Ibid., p.129]

Ebola and the Cult of Bankable Projects

During my second week in Monrovia the driver who brought me into the city and from office to office called in sick, possibly with malaria. Contracting Ebola requires an exchange of fluids with an acutely ill victim—unlikely for an expatriate spending minimal time outside officialdom. Even though I knew my safety was only a flight to London away, my mind still wandered: the virus’s early symptoms are not different from malarial fevers. Who was to say if someone, noticeably sweating yesterday and conspicuously absent today, was cycling through malaria or beginning a descent into something worse? What about the mangoes I was eating, fruit on which bats reportedly perch, feed, and transfer the virus? And how, no less, were the doctors getting sick through their hazmat suits? I washed my hands obsessively, but then the water stopped running from the taps—two days without a drop. One afternoon I walked from my office into a room where staff were being briefed on the virus, entering in time to hear someone say, “And then you bleed from all your orifices.” Yet I, like every scribbling pedant working on a project, carried along as if things were unchanged.

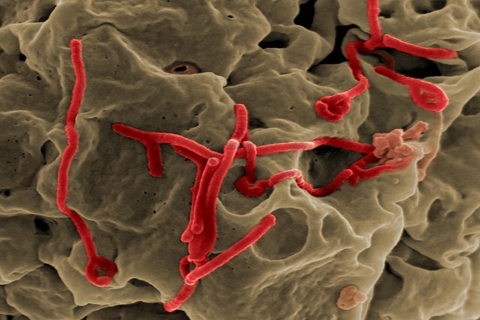

Ebola Virus. Courtesy of the CDC.

Ebola Virus. Courtesy of the CDC.

“Post-conflict” countries like Afghanistan, Angola, Colombia, Congo, Mozambique, Sierra Leone, Timor-Leste, and Liberia are magnets for global mining capital precisely because their infrastructure was destroyed, or never built, rendering the resources inaccessible. Over the past decade one hope for Liberia’s reconstruction was that mining investments could drive economic development, particularly by reviving the iron ore sector, whose contribution to GDP fell to 0.2 percent until the renewal of mining in the Nimba hills by ArcelorMittal in 2011. These investments contributed to a steadily rising GDP that analysts have used to demonstrate Liberia’s progress. But rather than a projected 7 percent growth rate, the World Bank is now forecasting just 3 percent growth in post-Ebola Liberia, while the other hardest hit countries—Sierra Leone and Guinea—are falling even more dramatically.[34. http://www.nytimes.com/2014/12/03/world/africa/new-concerns-over-response-to-ebola-crisis.html.] One thing Ebola illustrates is that without adequate public institutions and infrastructure, a resource boom is merely growth without development.

Project-driven international aid, meanwhile, contributed to the breakdown that enabled Ebola by routinely focusing on symptoms, not sources, of economic collapse. A barely functional government can hardly, for instance, verify every part of a supply chain without adequate transport to visit mines, no more than it can eliminate international smuggling when just a fraction of border crossings are patrolled. Ministries are saddled with administrative burdens, which, in the case of Liberia and the Kimberley Process, tax the government as much in membership fees as it gains in revenue from the mineral exports. “Liberia’s membership annually costs the government in excess of $400,000, the annual operating budget of the Government Diamond Office,” writes Ghent University researcher Steven Van Bockstael. “Since the removal of the UN export ban in 2007, annual revenues from diamond export royalties have consistently been below this amount.”[35. Van Bockstael, “The Persistence of Informality.”] The public profile of the Kimberley Process—one of the world’s most visible projects—leads one, naturally, to imagine Liberia as swimming in diamond revenues, yet the state officially loses money on its diamond trade.

Three days after completing my assignment in Liberia and returning to Canada, I was interviewed by another international development organization interested in having me manage projects in Liberia. We spoke for an hour without the subject of Ebola ever arising. Soon after, I was invited to speak to still another group vying for public financing—tens of millions of dollars—to run projects across West Africa. Again, Ebola was not part of the discussion. The feeling of cynical fraudulence was inescapable, as if I were a dentist who decided to hang out a shingle and dispense services for psychotherapy.

Fragile states are unable to cope with additional shocks like Ebola; without passable roads, electricity, and social solidarity there is no viable way to administer basic medical care or prevent minerals from illegally crossing porous borders, much less suddenly contain a runaway virus. Yet instead of addressing core issues of state failure, development aid continues pushing narrowly focused agendas that have little meaning in places where institutions and infrastructure are broken. Why, in response to the disastrous events we saw unfolding, were we not calling for public and private investment in the region to be shifted from one bureaucratic budget line to another? The money was there: everybody just wanted to spend it on other projects.

Shefa Siegel writes about resource governance and ethics, and has advised international organizations and development projects for over a decade, including the Earth Institute, United Nations, World Bank, and Natural Resources Canada. He has contributed articles on resources as well as religion and music to Haaretz, Sojourners, Yale Environment 360, and Americas Quarterly, and holds a PhD from the University of British Columbia. His previous essay for Ethics & International Affairs was “The Missing Ethics of Mining” (2013).

More in this issue

Spring 2015 (29.1) • Internal

Toward a Drone Accountability Regime: A Rejoinder

We appreciate the fact that our proposal initiated a lively discussion of the characteristics of a Drone Accountability Regime, and of the international political and ...

Spring 2015 (29.1) • Essay

The Informal Regulation of Drones and the Formal Legal Regulation of War

How does the proposed drone accountability regime relate to existing international treaty and customary law governing the use of force, including the use of lethal ...