Listen to a special Ethics & International Affairs interview with Jim Sleeper and EIA Senior Editor Zach Dorfman.

Introduction

It might seem an American Dream come true: About 100 Massachusetts Institute of Technology professors, ten at a time, are managing five laboratories stocked with “totally state-of-the-art equipment” in a gleaming new tower on the National University of Singapore campus. As the New York Times reports, the campus houses the Singapore-MIT Alliance for Research and Technology and other projects, involving “world-class universities from Britain, China, France, Germany, Israel and Switzerland.”[1. Jane A. Peterson, “M.I.T. Settles In for Long Haul in Singapore,” New York Times, November 16, 2014.] The MIT professors and their forty PhD and postdoctoral researchers are designing “myriad innovations”: driverless cars that would respond to “killer app” sensors throughout Singapore; stingray-like robots that will collect ocean-bottom data to fight noxious algae; and technologies that will track infectious diseases, energy consumption, and other movements in this tightly run, wealthy city-state of 5.4 million people.

Singapore’s government is also funding grants and expert advice for commercial start-ups by “world-class local talent,” including MIT’s Singaporean students, using MIT research. A Times photo shows Alliance director Professor Daniel Hastings taking his first ride on a driverless golf cart developed in the program, and he and his colleagues seem as happy as kids inventing gadgets in an American garage. “Singapore has the will to innovate,” one enthuses. “Its stature is increasing year by year,” says Hastings, noting that MIT, which has been in Singapore for fifteen years, is there “for the long term . . . . We like the model; it works for us."[2. Ibid.]

The professors’ almost boyish enthusiasm reminds me of the philosopher George Santayana’s century-old characterization of an American as “an idealist working on matter . . . successful in invention, conservative in reform, quick in emergencies. . . . There is an enthusiasm in his sympathetic handling of material forces which goes far to cancel the illiberal character which it might otherwise assume” and that spiritualizes the material things it encounters, thereby materializing the spiritual. Classically liberal in his individualism but democratic in his generosity, the American’s “instinct is . . . to wish everybody well [while] expecting every man to stand on his own legs and to be helpful in his turn."[3. George Santayana, “Materialism and Idealism in American Life,” in Norman Henfrey, ed., Selected Critical Writings of George Santayana Vol. 2 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1968), p. 58.]

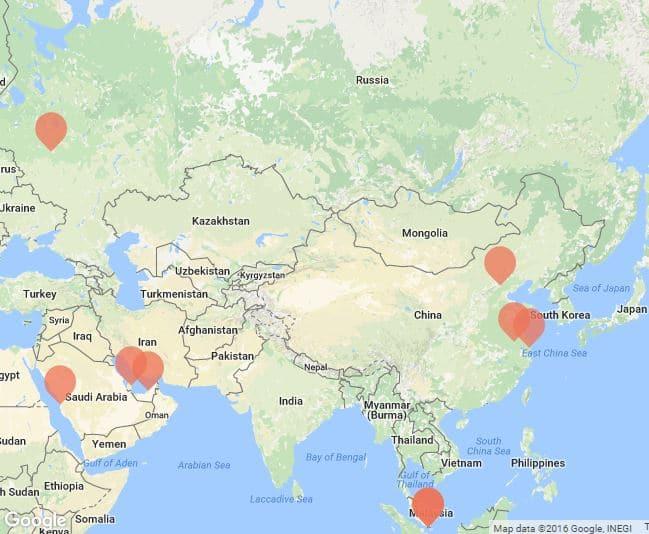

A quasi-missionary zeal to carry this ethos of trust and candor to other regions and minds is one of the “spiritual” reasons why American universities export at least 83 of the world’s nearly 219 branch campuses—physical educational facilities, or “footprints,” bearing American institutional names, although not always full American ownership.[4. This information provided by the State University of New York at Albany’s Cross-Border Education Research Team C-BERT, .] Thirteen of these American branch campuses are in China, seven are in Singapore, and fourteen can be found in Qatar and the United Arab Emirates.[5. Ibid.] There are hundreds more American university offices, research projects, pedagogical programs, and other engagements abroad. At the same time, among the more than 4.5 million students who attend universities outside their home countries each year, about 825,000 come to the United States while 300,000 Americans study abroad. The overwhelming majority of universities with physical presences in other countries are American or British. Globalization and its discontents are as unpredictable as they are irresistible, but Anglo-American liberal educators are avid navigators of its economic, demographic, and technological riptides, and there is something evangelical as well as inquisitive in their ventures, along with something materially acquisitive.

But can the American idealistic pragmatism that Santayana described “cancel” the illiberal character of hosts and partners in authoritarian regimes such as plutocratic Singapore, the theocratic/kleptocratic Emirates, neo-Orthodox (and newly belligerent) Russia, and, most fatefully, China, whose Ministry of Education reported late in 2014 that its universities hosted 223 programs and partnerships with American universities? China is all but certain to surpass the United States in economic power and international clout, and it has been moving aggressively to extinguish “Western values” in its universities, even while absorbing their know-how, in order to reassert itself as the serene center and summit of a decidedly illiberal, anti-Western, global civilization.

Not only are authoritarian governments and their rising middle classes increasingly assertive in acquiring higher education; Americans no longer seem quite sure of themselves as bearers of the classical liberal individualism and civic-republican fairness Santayana admired. Liberal arts colleges and even research universities that have long nourished citizen-leaders as well as scholars and that have sustained a messianic faith in liberal education itself are now licensing out professors, intellectual property, and institutional prestige to regimes bent on other purposes. By so doing, American universities may be legitimizing such regimes more often than liberalizing them. They may be offering students in those countries too narrow and instrumental a curriculum, compromising liberal education’s ethos and mission and, not incidentally, reinforcing and implicitly ratifying similar compromises at home.

Map of Select Branch Campuses, Institutes, and Research Centers of U.S. Universities Abroad

Map of Select Branch Campuses, Institutes, and Research Centers of U.S. Universities Abroad

What is at risk for liberal education?

Although the very word “university” suggests openness, practitioners of the liberal arts and sciences rely on certain premises and practices and proscribe others in order to discover, preserve, and disseminate knowledge. Traditionally, they have done this in collegiums, or self-governing companies of scholars, whose principals determine and care for their missions by standing apart from markets and governments in order to follow reason wherever it may lead. American liberal arts colleges and even research universities have been distinctive in working to diffuse liberal education’s habits of inquiry and expression not only among scholars but among the public at large. They have understood that a liberal capitalist republic has to rely on its citizens to uphold certain public virtues and beliefs—reasonableness, forbearance, a readiness to discover their larger self-interest in serving public interests—that neither markets nor the state do much to nourish or defend, and sometimes actually subvert. Good citizen-leaders must therefore be trained all the more intensively somehow, and American colleges have assumed that responsibility in ways and with results that have made them admired in much of the world.

Is this distinctively American liberal education transferrable? Are some efforts to transfer it making it less sustainable at home? I argue that American liberal educators have overreached. A few recent ventures that I discuss below, mainly in Singapore and China but with glances at other countries, illustrate how, by mistaking the “international” or “global” for the liberal and universal, they have committed themselves to regimes that exploit liberal education’s fruits but crimp its ways of discovering, preserving, and disseminating knowledge. Those ways can flourish in cross-border exchanges and collaborations undertaken by scholars themselves, but not so well in exchanges initiated by trustees and administrators who, thinking like managers of business corporations in the global marketplace, try to spread a university’s “brand name” and market share by selling or implicitly precommitting its pedagogy and its research. Doing this short circuits reason’s ability to assess openly the varied uses to which knowledge itself might be put; and I suggest that, in a worrying development, American liberal educators are being primed for such misappropriations of their work abroad by administrators who have already countenanced its misdirection at home.

To prevent that from happening, universities across the centuries have developed protocols for academic research and teaching to “encourage, and even require, that self-interested individuals who populate a university realize [disinterestedness] in its every function,” as University of Chicago classicist Clifford Ando put it to me.[6. Email exchange with the author.] Thanks to such requirements, polities where freedoms of inquiry and expression are well diffused accord their universities great respect and exempt them from taxation.

Disinterested scholarship’s two best, but fragile, defenses against corruption or conscription are, first, its expectation that persistent openness will generate widening, virtuous circles of trust; and, second, its hope that following reason toward truth will sustain more comity, freedom, and justice than would ideologizing and fortifying truths that serve unjust concentrations of power. If virtuous circles of trust turn vicious and engagement begins to reek of entrapment or commercialization, liberal educators may have to revise their strategies of engagement, for example by challenging or evading their hosts’ strictures. Or they may have to pull out completely. Such choices confront educators now in some countries where their universities have planted their flags.

Usurped or selling out?

When the iron curtain collapsed a quarter century ago, opening what seemed to be a world without walls, many Americans thought that freedoms of inquiry and expression would flourish. During a 1997 visit to China, President Bill Clinton told his hosts that they were “on the wrong side of history” in resisting liberal democracy, which capitalist development would inevitably bring about.[7. Orville Schell, “China Strikes Back,” New York Review of Books, October 23, 2014, p. 6.] But even as many societies embraced neoliberal economic premises and practices, their rulers have struggled to balance its benefits with its social dislocations, which have inflamed popular resentments more than liberal-democratic yearnings. Elites straddling that fault line have been trying to clothe their state-capitalist modernizing in the trappings of old religious and mythic traditions (Hindu, Confucian, Russian Orthodox, and Ottoman, among others)—a move designed to temper capitalist excess while fortifying the state's iron-fisted control. At the same time, some of these states have also sought to adapt liberal higher education’s organizational and strategic strengths to consolidate their power.

Skolkovo Institute of Science and Technology, Moscow, Russia. fotiyka / Shutterstock.com

Skolkovo Institute of Science and Technology, Moscow, Russia. fotiyka / Shutterstock.com

For example, MIT is being paid $300 million by the Russian government to head up research at the new Skolkovo Institute of Science and Technology, which was founded in 2011 as part of former President Dmitry Medvedev’s $2.7 billion answer to Silicon Valley. The collaboration, MIT spokesman Nathaniel Nickerson told Bloomberg News, is building “a new institutional paradigm bringing together education, research, and innovation” based on “intellectual relationships in a transparent environment, centering on open, fundamental, publishable research.” It sounds good, but in 2013 President Vladimir Putin, feuding with Medvedev, vetoed benefits for the project’s technology park, and government agents “raided the foundation overseeing the university in a corruption probe.”[8. See Oliver Staley, “Duke to NYU Missteps Abroad Lead Colleges to Reassess Expansion,” Bloomberg Business, October 4, 2013.] In 2014 the FBI warned MIT and American tech companies in the complex to be vigilant against misappropriations of research and technology with national defense applications.[9. Carl Schreck, “FBI Wary of Possible Russian Spies Lurking in High-Tech Sector,” Voice of America News, May 20, 2014.] Although MIT cannot be faulted for failing to anticipate these specific legal and political difficulties, it should have considered that in Russia, as in Singapore, it cannot rely on independent judiciaries and other guarantors of the rule of law to protect scholarship and teaching from misappropriation.

Some host regimes openly herald the passing of Western premises and power: “The Chinese aren’t trying to coexist with us; they’re offering to buy us,” notes Orville Schell, director of the Asia Society’s Center on U.S.-China Relations. And not because they intend to emulate us.[10. Interview with author, February 5, 2015.] Something very different is on order, a dispensation in which Americans may find themselves subordinate in new and discomfiting ways. In Singapore, the late Lee Kuan Yew, founder of that nation in 1965, was an early apostle of “Asian values” against Western presumptions, but, having read law at Cambridge, he, like other authoritarian rulers with a Western education, also tried to apply liberal education’s grace notes to illiberal practices. Singapore’s generous funding of MIT research captures that university’s world renowned imprimatur while enhancing not only benign transportation and health-care innovations but also the regime’s capacity to blanket its island with monitoring devices. This has made the country “a laboratory not only for testing how mass surveillance and big-data analysis might prevent terrorism, but for determining whether technology can be used to engineer a more harmonious society,” as Foreign Policy has reported in eerily cheery detail.[11. Shane Harris, “The Social Laboratory,” Foreign Policy, July 29, 2014.]

Singapore has eagerly embraced the Total Information Awareness program, which was created by the U.S. National Security Administration but then curbed (and renamed) in the face of U.S. constitutional strictures, Edward Snowden’s revelations, and American political culture’s deep strain of skepticism about government overreach. No such constraints curb Singapore’s efforts to monitor its residents’ actions and even “moods” through patterned investigations of their email messages, phone calls, and physical movements. MIT’s experiments may not be driven explicitly by government directives or commercial contracts that would compromise the pursuit of knowledge, but it is not a stretch of the imagination to foresee the resulting technologies being used for such public surveillance.

Similarly, Saudi Arabia and the Emirates have poured billions of dollars into “education cities” hosting scores of American-university branch campuses that enjoy varying degrees of independence. Qatar’s National Research Foundation, designed with guidance from the RAND Corporation, funds specific research projects in partnerships with Virginia Commonwealth, Cornell, Carnegie Mellon, Texas A&M, and Georgetown universities to—as the foundation puts it—build human capital in Qatar, advance research “in the interest of Qatar, the region, or the world,” and “raise Qatar’s international profile in research.”[12. "Report: Launching the Qatar National Research Fund,” Rand-Qatar Policy Institute (2012), www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/technical_reports/2012/RAND_TR722.pdf.] In Saudi Arabia, grants from the King Abdullah University of Science and Technology go only to research of interest to Saudi Arabia’s government. That may not compromise a project on, say, water desalinization or carbon capture, but it might limit public uses and dissemination of the research.[13. Waleed al-Shobakky, “Brave New World: Gulf Seeks Bold Science Initiatives,” Sci Dev Net, July 2, 2008.]

The role of globe-trotting administrators

“It’s easy to get addicted to any sort of funding in tough budgetary times,” warns Jeffrey Wasserstrom, Chancellor’s Professor of Chinese History at the University of California Irvine.[14. “The Debate Over Confucius Institutes,” ChinaFile, June 23, 2014.] Fiscally strapped American university administrators have made questionable accommodations to practices that compromise academic integrity at home. In one among many recent scandals, the New York Times reported in 2008 that Virginia Commonwealth University (one of the Qatar National Research Foundation’s first partners) had agreed not to discuss or publish the results of studies funded by the tobacco giant Philip Morris and that it would not even respond to inquiries about the agreement itself. “There is restrictive language in here,” Virginia Commonwealth’s vice president for research acknowledged to the Times, but, even in admitting that it violated most university guidelines for university-sponsored research, he called it “a balancing act.”[15. Alan Finder, “At One University, Tobacco Money Is a Secret,” New York Times, May 22, 2008.]

Donors with ideologically driven foreign-policy agendas have funded campus institutes and teaching programs at Yale and other universities, influencing the work of professors who should have been restrained by liberal requirements and protocols from advocating or otherwise promoting political and commercial ventures. Clifford Ando observes a “gradual abandonment . . . of the principles by which universities once organized themselves internally and situated themselves in the nation at large” and a proliferation of “research for hire and new centers or institutes immune from the systems of evaluation that universities otherwise deploy.”[16. Email exchange with the author.]

Administrators looking abroad often exclude their own universities’ scholarly experts on the relevant societies and governments from their assessments and planning, let alone their negotiations. NYU’s rapid global expansion, especially into Shanghai, prompted Rebecca Karl, an associate professor of East Asian Studies and a member of the Faculty Senators Council, to criticize “the non-consultative nature of the NYU leadership, where huge policy decisions about the structure of the university are taken and then all of the sudden we the faculty are apprised of it in the aftermath.”[17. Elizabeth Redden, “Global Ambitions,” Inside Higher Ed, March 11, 2013.] Similarly, Yale’s administration and corporation apprised its faculty of the university’s commitment to enter a joint venture with Singapore to establish a liberal arts college bearing Yale’s name only when that undertaking had already been signed and sealed. Further, the full terms of the contract have never been shared with the faculty. In what was widely understood as a rebuke to the Yale administration, the faculty’s Southeast Asia Studies Council joined with an undergraduate organization to bring to New Haven two leaders of tiny opposition parties in Singapore who have been harassed and suppressed there.

Amy Stambach, a professor of educational policy and anthropology at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, suggests that university administrators try to reconcile two ways of pursuing cross-border higher education: the first, the “global marketplace” model, assumes that university competition for scholars and their research enhances the production of knowledge itself; while the second, “the global commons” model, posits that knowledge flourishes best by circulating freely and that universities therefore deserve more disinterested support in generating it. Both models are variations on a liberal theme, Stambach notes, but some host countries make only a pretense of following either one and, like Philip Morris, assume a cash-and-carry approach to university research.[18. Amy Stambach, “Cross Border Higher Education: Two Models,” International Higher Education, no. 66 (Winter 2012).]

The Boston of Southeast Asia?

Singapore, eager to displace Hong Kong and stay ahead of Malaysia as “the Boston of Southeast Asia”—a hub for global universities and for what its ambassador to the United States, Chan Heng Chee, has called “the education industry”—boasts a dozen branch campuses, partnerships, and other programs involving Western universities.[19. Ambassador Chan Heng Chee, “Democracy, Globalisation and Competitiveness in Singapore” (talk at the Yale Law School, New Haven, Conn., March 8, 2012), www.law.yale.edu/documents/pdf/News_&_Events/Singaporeambassadortalk.pdf. See also Jim Sleeper, “Yale Has Gone to Singapore, But Can It Come Back?” Huffington Post, July 4, 2012, www.huffingtonpost.com/jim-sleeper/yale-has-gone-to-singapor_b_1476532.html.] Bertil Andersson, president of Singapore’s Nanyang Technical University, characterizes the country as “Asia lite” for Western university partners. Indeed, it can seem so next to China’s increasingly intrusive, iron-fisted policies toward higher education. But the country has other distinctions. In 2015, Reporters Without Borders ranks Singapore’s press freedoms an abysmal 153 out of 180 nations on its sophisticated World Press Freedom Index. That is down from 135 in 2012, when the government began a crackdown on political websites.

Singapore also deploys Kafkaesque legalism to restrain artistic expression and political activity. In Authoritarian Rule of Law, the legal scholar Jothie Rajah distinguishes democratic rule of law (in which citizens have some voice and some power) from the rule by law. Relying on the latter, Singapore’s ruling party, using its control of Parliament and the judiciary (and of the press) passes and enforces repressive laws by invoking “emergencies”; orchestrating public denigrations of critics in “hearings” that are really show trials; infantilizing citizens by claiming to look after their best interests paternally; and wording its statutes vaguely to leave the state room to manipulate laws as it wishes.[20. Jothie Rajah, Authoritarian Rule of Law: Legislation, Discourse and Legitimacy in Singapore (New York: Cambridge Studies in Law and Society, 2012).] Human Rights Watch calls Singapore “a textbook example of a repressive state.”[21.Isaac Stone Fish, “A Different Kind of Freedom,” Newsweek, January 27, 2010.] About a fourth of its population—some 1.3 million people—are virtually rights-less migrant workers.

Almost every year has brought an instance, and sometimes international condemnation, of the persecution of a professor who has criticized the regime or whose scholarship in history, political science, or law seems to threaten it.[22. Bertil Andersson’s Nanyang Technical University caused an international outcry by refusing to tenure Cherian George, a Stanford-trained media studies professor whose sophisticated analyses of press freedom had been cited by apologists for the Singapore regime as proof that dissent is possible. Andersson insisted the decision was “not political,” but George has had to find a new position at Hong Kong Baptist University. See Jess C. Scott, “Singapore: Academic Freedom?” The Real Singapore, February 21, 2014.] Johns Hopkins University, University of Chicago, Australia’s University of New South Wales, and New York University’s Law School and Tisch School of the Arts have all pulled programs out of Singapore. Additionally, Britain’s venerable Warwick University and America’s distinguished Claremont, Haverford, Williams, and other liberal arts colleges have all rebuffed the country’s invitations to establish a liberal arts college there. “In a host environment where free speech is constrained, if not proscribed, . . . authentic liberal education, to the extent it can exist in such situations, will suffer,” warned the American Association of University Professors (AAUP) in an open letter to the Yale community.[23. American Association of University Professors, “An Open Letter from the AAUP to the Yale Community” (2012).] This worry is being borne out by experience: MIT faculty in Singapore report difficulty, for example, in “getting students to interact” and to “feel safe to voice an opinion or ask a question without fearing repercussions.”[24. Peterson, “M.I.T. Settles In for Long Haul in Singapore.”]

Confident that they had anticipated all such snares, Yale University’s president and trustees in 2009 commingled the college’s historically missionary sensibility and its long intimacies with American economic statesmanship and strategic foreign policymaking to partner with Singapore to found an undergraduate liberal arts institution: Yale-National University of Singapore College (Yale-NUS). The college is funded wholly by Singapore, a country whose sovereign wealth funds have long been advised and invested in by three of the Yale trustees. In response to this announcement, faculty in New Haven registered “concern regarding the recent history of lack of respect for civil and political rights in the state of Singapore” and urged Yale-NUS to protect ideals that lie “at the heart of liberal arts education as well as of our civic sense as citizens [and] ought not to be compromised in any dealings or negotiations with the Singaporean authorities.”[25. Seyla Benhabib, “What’s at Stake at Yale-NUS?” Yale Daily News, April 4, 2012.] The faculty resolution, passed in 2012 over Yale President Richard Levin’s objections, played a part in his announcement four months later that he would resign the following year.

Yale-NUS Brochure. Via the Yale-NUS Blog, "The Liberal Arts in Singapore."

Yale-NUS Brochure. Via the Yale-NUS Blog, "The Liberal Arts in Singapore."

Undeterred, the Yale Corporation, administration, and selected professors joined with new colleagues to “reinvent liberal education from the bottom up” in an intriguing new curriculum that was introduced in August 2013 to the Yale-NUS inaugural class of 157 carefully selected students, more than 60 percent of them Singaporean, in its new panopticon of a campus. Pericles Lewis, a Yale professor of comparative literature who became Yale-NUS’s first president, struck an idealistic note by invoking John Stuart Mill: “It is hardly possible to overstate the value of placing human beings in contact with persons [and] modes of thought and action unlike those with which they are familiar,” he wrote, adding that “progress depends on continued engagement and dialogue rather than retreat or insularity.”[26. “Presidential Statements Regarding Yale-NUS College: Statement by Yale-NUS President Pericles Lewis,” July 19, 2012.]

But such noble sentiments, amply vindicated when a fine teacher inspires students to probe worlds beyond their own,[27. See Professor Mark R. Cohen’s moving account “What I Learned Teaching Arabs About Judaism in Abu Dhabi,” The Jewish Daily Forward, February 8, 2015, http://forward.com/news/214236/what-i-learned-teaching-arabs-about-judaism-in-abu/.] fade into truisms when expressed by university administrators hot in pursuit of international funding and prestige. “Engagement” and “sensitivity” can work magically well in free classrooms, but become weasel words on the lips of administrators and faculty apologists encountering subtler but harsher realities. “What we [Americans] think of as freedom, they [Singaporeans] think of as an affront to public order,” said Yale-NUS’s inaugural dean, Charles Bailyn, in 2013, trying to relativize if not justify Singapore’s prohibitions of public assembly.[28. Ava Kofman and Tapley Stephenson, “Yale Values to be Tested in Singapore,” Yale Daily News, March 29, 2012.] The AAUP’s open letter concerning Yale-NUS posed sixteen questions that Yale has not answered, perhaps because it has yet to make public the terms of its contract with NUS, where administrators must approve even minor expenditures from professors’ allotted research funds. Such “light touch” repression, dismissed as a mere formality, can chill freedom in ways students may not detect.[29. American Association of University Professors, “An Open Letter.”]

The global village's serene center?

China’s economy is projected to be twice the size of the United States’ by 2030, and its trade strategies in Africa and Latin America may soon make the West beg for access to raw materials for the first time since the seventeenth century. Watching container ships unload in Valparaíso, Chile, a few years ago, I marveled that most of the containers were Chinese and learned that China buys 60 percent of the copper from Chile’s vast mines. That does not make the world flat, for China maintains, and lately has been touting, its ancient, quasi-Confucian self-understanding as the serene summit of a global village and marketplace to which all others will pay tribute.

Soon after Xi Jinping became China’s president in 2013, State Document No. 9 listed seven “subversive currents” not to be spoken of, including “universal values” such as human rights, press freedom, judicial independence, and economic neoliberalism. (Any mention of the historic mistakes of the Communist Party was also deemed subversive.) In 2015, Education Minister Yuan Guiren ordered universities to “never let textbooks promoting Western values appear in our classes,” adding that “remarks that slander the leadership of the Communist Party of China” and “smear socialism” must never appear in college classrooms.[30. See “China Says No Room for ‘Western Values’ in University Education,” Guardian, January 30, 2015, ; and William Ide, “China’s Western Values Debate Heats Up Online,” Voice of America, February 4, 2015, www.voanews.com/content/china-western-values-debate-heats-up-online/2628748.html.]

China’s tightening is not only internal: 97 Confucius Institutes (CIs) have been fully funded and staffed by China on campuses in the United States (with more than 350 CIs in other countries, and a projected world total of 1,000) to teach Chinese language and culture in pre-scripted ways. An important recent debate about CIs by well-informed American scholars and journalists at Chinafile.com[31. “The Debate Over Confucius Institutes,” ChinaFile.] shows that Confucius Institutes sometimes muscle out American host universities’ own independent scholars on China, not only by offering them free Chinese language instruction but also by pressuring them to disinvite uncongenial speakers and cancel public discussions of “forbidden” topics, including Tibet, Taiwan, and Tiananmen. CI directors monitor the work and pronouncements not only of their own teaching staff but also of their nominal American colleagues, who, if they criticize China, may suddenly find it difficult to obtain visas to continue research there. The effect is to “intimidate and punish” scholars, Chinese and Western, who challenge Beijing’s agendas, says Perry Link, the University of California professor who testified about China’s academic modus operandi before the U.S. House Foreign Affairs Committee in late 2014.[32. Testimony of Perry Link, Chancellorial Chair at the University of California, Riverside, at the hearing before the U.S. House Committee on Foreign Affairs, 113th Cong. 2 (2014) on “Is Academic Freedom Threatened by China’s Influence on American Universities?”]

Skyline in Hefei, China. Via Flickr. Courtesy of Tao Wu.

Skyline in Hefei, China. Via Flickr. Courtesy of Tao Wu.

To head off suspicions that they accept such developments, institutional members of the American Association of Universities and two other international associations met in Hefei, China, in October 2013 with representatives of nine elite Chinese universities that host Western university projects and programs to sign the “Hefei Statement.” The statement pledged “to identify the key characteristics that make research universities effective; and to promote a policy environment which protects, nurtures, and cultivates the values, standards, and behaviors which underlie these characteristics and which facilitates their development if they do not already exist.” The Hefei Statement asserts that all universities are entitled to “autonomy” and to “responsible” academic freedom, and that “government fiat alone cannot create a research university. Such institutions are built from within, by university administrations having the strategic vision and operational excellence necessary to secure from multiple sources the funding needed to build the facilities and to recruit [faculty], across a broad range of disciplines.” This is true as far as it goes, but the statement nowhere acknowledges or even hints that “university administrations” in China are wholly appointed and controlled by the government and ruling party, as are their counterparts, with minor variations, in Singapore, the Emirates, the central Asian republics, and other nations whose regimes host American universities. The hosts and their guests enjoy only fig-leaf independence.

“Two words remind us that Beijing sometimes pretends that old promises were never made or if made don’t need to be honored: ‘Hong’ and ‘Kong,’” says China historian Jeffrey Wasserstrom.[33. “The Debate Over Confucius Institutes,” ChinaFile.] Even veteran China watchers who have learned to be skeptical of draconian pronouncements like Guiren’s (as well as of more constructive ones like the Hefei Statement) might agree with Mary Gallagher, an associate professor of political science and director of the Center for Chinese Studies at the University of Michigan, that the crackdown is “not just going to be about social activists, NGOs, political dissidents . . . [but about] telling people what they could or could not talk about in the classroom,” and that it “will be a huge challenge to Western universities as they begin to open facilities in China and do more collaborative programs with Chinese universities.”[34. Elizabeth Redden, “Has China Failed a Key Test?” Inside Higher Ed, October 21, 2013.]

New York University certainly faces such a challenge. It characterizes its new campus in Shanghai, a joint venture with East China Normal University, as one of two “portals” to what President John Sexton calls a Global Network University, which he also characterizes as an “organic circulatory system.” NYU has another large portal in its huge, stand-alone NYU Abu Dhabi campus, as well as the original anchor portal in New York, and twelve “Study Away Sites” on four continents. Its undergraduate Stern Business School—named for trustee Leonard Stern, the Hartz Mountain pet foods magnate—“allows students who opt for ‘Stern World’ to do five semesters in New York, one in London, one in Shanghai, and one in Abu Dhabi—all with . . . quality at the level NYU demands.”[35. John Sexton, “Global Network University Reflection,” New York University, December 21, 2010.]

The result is really a presidents’ and trustees’ dream of globalization from the top, but the dreamers have blundered into sticky entanglements that will compromise liberal education beyond recognition. In Abu Dhabi, where NYU’s campus is the product of a kleptocracy that also pays most students’ tuition, most of the compromises involve not just academic life but the virtual indentured servitude of thousands of laborers from Southeast Asia who have been imported to construct the campus. In March 2015, Abu Dhabi barred NYU American Studies professor Andrew Ross, who has called attention to the labor abuses, from entering the country.[36. Stephanie Saul, “N.Y.U. Professor is Barred by United Arab Emirates,” New York Times, March 16, 2015.] In the United States, Ross was followed by a private investigator; and a reporter who had worked with the New York Times on a story about the Abu Dhabi campus said that a representative of the United Arab Emirates had offered him payments to write more positively about the government.[37. Jim Dwyer, “Murky Inquiry Targets Critic of N.Y.U. Role in Abu Dhabi, and a Reporter” New York Times, March 26, 2015, www.nytimes.com/2015/03/27/nyregion/investigator-for-mystery-client-targets-critic-of-nyu-role-in-abu-dhabi.html.]

President Sexton’s handling of reports about those abuses and of NYU’s complicity in them are troubling. His characterization of NYU Shanghai as part of his university’s global “organic circulatory system” is even more troubling academically, given China’s controlling interest in NYU’s joint venture with East China Normal University, on a campus built wholly by China. East China Normal University has control of the “cooperator’s” intellectual property if it is used—in an academic context—“as an educational investment.” The state, working with the Communist Party, has imposed on all its universities new demands and punishments as part of its larger strategy to absorb their Western partners’ know-how while rebuffing “Western values” at home and advancing Chinese intellectual and cultural alternatives to liberalism around the world. Chinese state documents have referred to its two major campus-based joint ventures—with NYU in Shanghai and with Duke University in Kunshan, forty miles to the west—as pilot programs for new models of cooperation. But its policies and practices reflect a drive to inoculate its own students on these campuses against whatever liberal ideas they may encounter, and to indoctrinate Western visitors in a Chinese alternative to liberal democracy and, indeed, liberal education. How effective and sustained this strategy will be remains to be seen, but American university administrators who entered into such partnerships with liberal expectations can feel the ground shifting under their feet.

Evade, resist, depart?

Too many American administrators seem not to acknowledge such shifts, even when they are experiencing them. In 2011 graduate students of international relations at Johns Hopkins-Nanjing Center—whose website describes it as a place “for genuinely free and open academic exploration and intellectual dialogue”[38. Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies, homepage, www.sais-jhu.edu/graduate-studies/campuses/nanjing-china#about.]—were barred from using a center lounge to show a documentary about the Tiananmen uprising and from distributing a student journal. A dean advised a Chinese student to remove his article from the journal, and Hopkins-Nanjing “administrators removed the word ‘center’ from the journal’s title so that it didn’t appear to be an official publication,” its student editor told Bloomberg News.[39. Daniel Golden and Oliver Staley, “China Halts U.S. Academic Freedom at Classroom Door for Colleges,” Bloomberg Business, November 28, 2011.] Center codirector Jan Kiely told frustrated students that academic freedom “doesn’t include being able to put Chinese students and professors in a very difficult position in their own country.” Hopkins President Ronald Daniels was almost as evasive: “Is it what we would desire for every project, every center we’re involved in? The answer is no. We would hope over time that the scope for discussion can extend beyond the center.” Carolyn Townsley, director of the center’s Washington office, extended the discussion only to blame students: “If you want understanding, you don’t constantly antagonize people.”[40. Ibid.]

Duke University officials, learning of the crackdown in Nanjing while working on their new campus in Kunshan, had “some pretty good conversations with people at Hopkins” and decided to draw similar distinctions between “intra-campus discussion and what you do at large,” Duke President Richard Brodhead told Bloomberg News. “If you want to engage in China, you have to acknowledge that fact,” he added.[41. Ibid.] Nora Bynum, the vice provost for Duke Kunshan, touted the Hefei Statement, adding, “We think it’s very important to take an active and engaged response to these kinds of issues.”[42. Elizabeth Redden, “Has China Failed a Key Test?,” Inside Higher Ed, October 21, 2013.] Other Americans are more forthright. “The one thing we have to do is maintain our academic integrity, our academic independence,” says Lee Bollinger, president of Columbia University, whose eight “learning centers” abroad can be withdrawn quickly if their freedom is imperiled. “There are too many examples of a strict and stern control that lead you to think that this is kind of an explosive mix,” Bollinger warns.[43. Ibid.] So does Morton Schapiro, president of Northwestern University and an economist who studies higher education. “There’s nothing wrong with pulling the plug,” Schapiro told Bloomberg News. “What’s wrong is staying there when it’s not working.”[44. Staley, “Duke to NYU Missteps Abroad Lead Colleges to Reassess Expansion.”]

Wellesley College has taken a middle course with Peking University, which is sometimes characterized as the Harvard of China. Peking is a locus for partnerships of different sorts with Wellesley, Stanford, Columbia, Cornell, and the University of Michigan. As Peking signed the Hefei Statement in 2013, it was preparing to fire Xia Yeliang, an economist who had joined in drafting Charter 08, a statement to end China’s one-party Communist rule. When the news reached Wellesley, 130 faculty members sent Peking a letter warning that Xia’s dismissal would jeopardize the partnership. Peking fired him anyway, stating—as Singapore’s Nanyang Technical University had in denying tenure to Cherian George—that it was doing so only for academic reasons. Wellesley balanced resistance with pointed engagement by setting up a “Freedom Project” that made Xia a visiting fellow at Wellesley while continuing its Peking partnership—a gentle provocation to its partner to live up to the Hefei Statement. “We’re not telling them to adopt the Bill of Rights,” said Wellesley sociologist Thomas Cushman. “We’re asking what it means for Wellesley to work with a regime that instills fear in people.”[45. Tamar Lewin, “U.S. Colleges Finding Ideals Tested Abroad,” New York Times, December 11, 2013.] Yet Xia’s firing prompted silence or evasion from Peking’s other American partners. Richard Saller, dean of the School of Humanities and Sciences at Stanford, which has a $7 million center at Peking University, told the New York Times’ Tamar Lewin, “We went into our relationship with Peking University with the knowledge that American standards of academic freedom are the product of 100 years of evolution. We think engagement is a better strategy than taking such moral high ground that we can’t engage with some of these universities.”[46. Ibid.]

Graduation Ceremony at Carnegie Mellon. Via Flickr. Courtesy of drpavloff.

Graduation Ceremony at Carnegie Mellon. Via Flickr. Courtesy of drpavloff.

Perhaps the best strategic suggestion comes from a nonacademic, David Schlesinger, who studied Chinese politics for a master’s degree at Harvard and was chairman of Thomson Reuters China. Drawing upon this experience in a discussion with China scholars, Schlesinger advises university representatives to stand their ground in asserting freedoms of inquiry and expression: “Just as China repeats its ‘principled stands’ on Taiwan, Tibet, human rights . . . so I, too, when I worked for Reuters, would use that company’s Trust Principles and fundamental journalistic values as the introduction to any official meeting. If your principles are strong and steadfast, they become something that has to be dealt with. If your principles can be rethought and changed, they become simply a negotiating point.”[47. “The Bloomberg Fallout: Where Does Journalism in China Go from here?” ChinaFile, March 26, 2014.]

Wellsprings

Is anything in liberal education nonnegotiable? In 2013 the Yale-NUS founding faculty met for months in Betts House, a mansion on a hill overlooking much of the Yale campus in New Haven, in order to design an unprecedented curriculum for their “new community of learning” in Singapore. Here, Pericles Lewis believed he was witnessing “the liberal arts experience made manifest,” and he anticipated “a place of revelatory stimulation” in the new campus on the other side of the world.[48. Eric Gershon, “Report Details Fresh Take on the Liberal Arts,” Yale News, April 8, 2013, news.yale. edu/2013/04/08/report-details-fresh-take-liberal-arts.] Yale itself was founded by graduates of an older university—at Cambridge, in England—who intended to carry revelatory stimulation across an ocean to a strange people in a strange land. Like the Yale-NUS founders, they intended their new “city upon a hill” to set an example for both their coreligionists and their oppressors back home, where their faith was beleaguered, as liberal education is in America now.

Of course, their incentives were commercial as well as missionary: the first arrivals on the Mayflower—among them, the Elder William Brewster, a direct ancestor of Kingman Brewster, Jr., Yale’s president of the late 1960s and early 1970s—needed material support from Native Americans and were beholden to investors back home. Eighty years later, Yale’s Puritan founders sought a benefactor in Elihu Yale, a governor of the East India Company, one of the world’s first multinational corporations (and, a century later, the acquirer of the island of “Singapura” for the British crown). Yet the Americans’ missionary strain never died. It was made manifest hundreds of years later in “The American Century,” the 1941 essay heralding America’s world-saving dominance following World War II, written by Time magazine cofounder Henry Luce, the China-born son of Yale missionaries there. A strain of it is also evident in the work of the Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist John Hersey (Yale ’36), himself a descendant of Massachusetts Puritans, notably in his novel The Call, about missionaries like his own parents in China, where Hersey was also born. It was manifest, too, in Yale President Alfred Whitney Griswold, a descendant of Puritan governors of Connecticut, who defended liberal education during the Cold War not only against communism but also against McCarthyism and national security-ism; and in Kingman Brewster, Jr., who awarded an honorary doctorate to Martin Luther King, Jr., in 1964, when more than a few Yale alumni still considered King a lawbreaker and rabble rouser.

Now that Yale, like other American universities, resembles a global business corporation more than a self-governing, civic-republican company of scholars, the more idealistic Yale-NUS founders in Singapore hope that their example will spur a transformation back home. They are more likely, however, to effect the all-too-smooth convergence of Asian and American state capitalism mentioned earlier.

John Winthrop warned against succumbing to the “carnall lures” of wealth-making that he feared would reduce knowledge to mere know-how and deep faith to frantically worldly works. The world is not flat, the Puritans insisted; it has abysses, opening unpredictably at our feet and in our hearts, and the young need a community of mutual trust that is strong enough to help them plumb those depths, face demons in them, and even defy worldly powers in the name of a higher one. Puritans did not live up to that ideal, but, almost despite themselves, they sowed civic-republican seeds and standards that the humanities took up in colleges, and that continued to nourish the ethic of mutual responsibility that lay deep in their origins and traditions. For three centuries the old colleges struggled, in Calvinist and classical ways, to temper capitalist wealth-making and civic-republican power-wielding with religious or humanist truth-seeking.

Every liberal arts college should still be doing that, all the more so because of the new challenges that we face. When Luce limned the American Century with Puritan fervor in 1941, the United States bestrode the world, riding the twin horses of civic-republican nationalism and industrial capitalism. The horse of capitalism has slipped its American harness and galloped off to China, turning the old mission back upon itself and exposing sinkholes in what had seemed a bedrock foundation. Liberal arts missionaries and mercenaries may seek more help now from hosts abroad than the latter seek from them. But too desperate a convergence will yield to codependency or a conflict the West may not win.

A PDF version of the article is available to subscribers only. Click here for access.

More in this issue

Summer 2015 (29.2) • Interview

An Interview with Jim Sleeper on the Future of Liberal Education

JIM SLEEPER AND ZACH DORFMAN In this EIA interview, Jim Sleeper, author of "Innocents Abroad: Liberal Educators in Illiberal Societies," talks about the expansion of ...

Summer 2015 (29.2) • Feature

Just War Theory and the Last of Last Resort

Last resort should be jettisoned from the just war tradition because adhering to it can require causing or allowing severe harms to a greater number ...

Summer 2015 (29.2) • Review

Reason in a Dark Time: Why the Struggle Against Climate Change Failed—and What It Means for Our Future by Dale Jamieson

Jamieson is interested in the real rather than the ideal world. The result is a book that is uncommonly accessible to nonspecialists, and will resonate ...