The Sahrawi people, who have long lived in the western part of the Sahara, have been housed in refugee camps in Tindouf, Algeria, since 1975—the year that Morocco took de facto control of Western Sahara. Their situation poses many questions, including those regarding the status of their state-in-exile, the role of the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic, and the length of their displacement. The conditions in the Tindouf camps present a paradigmatic case study of the liminal space inhabited by long-term refugees. Over the decades, residents have transformed these camps into a state-like structure with their own political and administrative institutions, which has enabled the international community to gain time to search for an acceptable political solution to the long-term conflict between the Polisario Front (the Sahrawi rebel national liberation movement) and the Moroccan government. The existence of a state-like structure, however, should not itself be understood as the ultimate solution for the thousands of people in these camps, who are currently living in extreme poverty, surviving on increasingly meager international aid, and enduring an exceptionally long wait for the favorable conditions whereby they may return to their place of origin.

This essay is divided into three sections. First, it addresses the question of the Western Sahara from a historical point of view. The three major phases of the Sahrawi-Moroccan conflict provide the context for the formation and the current situation of the Sahrawi refugee camps. Second, it touches on the implementation of durable solutions for refugees living in camps and the supposedly transitional role of these spaces in such solutions. Finally, the essay applies an analytical framework to the paradigmatic case of the Sahrawi, demonstrating the contradictions between the theoretical model used to understand protracted refugee situations and the permanent problem regarding the rights of refugees.

First Phase: The Departure of Spain and the Start of the Sahrawi-Moroccan War

The Sahara conflict is rooted in the unfinished decolonization process started by Spain in 1975. A few days after the death of Francisco Franco, with his dictatorial regime in disarray, Spain ceded the “Spanish Sahara” to Mauritania and Morocco with the signing of the Madrid Accords.[1. The agreements were nullified by the United Nations. However, the physical occupation of territory and the failure to resolve the conflict consolidated Morocco as the de facto “administrator” of the territory.] Spain officially left the territory on February 26, 1976, although Morocco and Mauritania had months earlier entered the territory. The occupation of the territory by both countries galvanized the Sahrawi resistance movement—a movement that had begun in the late 1960s stirred by the decolonization processes on the African continent. In 1973 the resistance to the Spanish presence coalesced around the Popular Front for the Liberation of Saguia El Hamra and the Río de Oro (Polisario Front), and this alliance confronted the Mauritanian army from 1975 to 1979 and the Moroccan army until 1991.[2. On the history of the conflict see José Ramón Diego Aguirre, Guerra en el Sahara (Madrid: Ediciones Istmo, 1991).] The first months of the conflict forced Sahrawi civilians to flee to Algeria’s Tindouf region, where, with the help of the Algerian state[3. Algeria’s support for the Polisario Front should be understood in the context of enmity with Morocco over territory and leadership of the North African region in their confrontation in 1963 in the “War of the Sands.” For more information see Khadija Mohsen-Finan, Sahara Occidental: Les enjeux d’un conflit regional (Paris: CNRS Editions, 1997).] and the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), the Polisario Front established refugee camps.

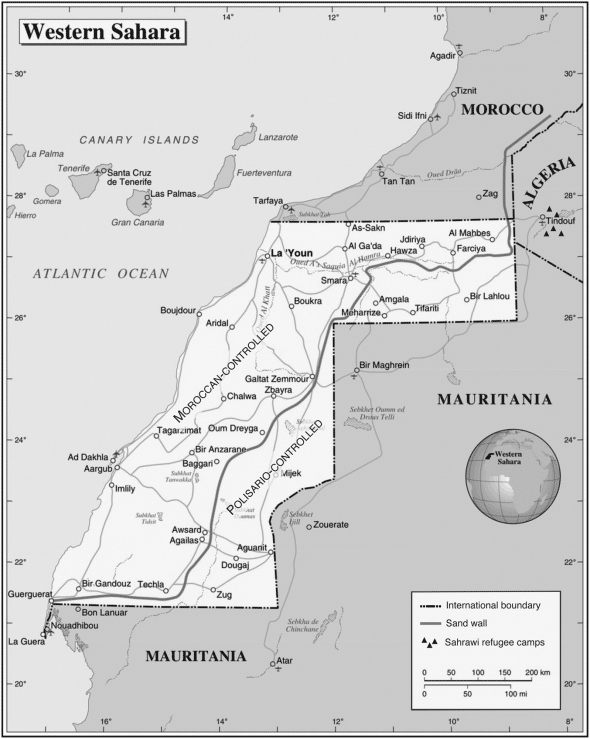

There were a number of significant developments during the sixteen-year war. These included the Polisario’s acquisition of a third of the territory of Western Sahara—the so-called “liberated territories”—and the construction by Morocco of an extremely militarized 2,700 kilometer defensive wall, which separates the occupied and liberated lands of Western Sahara (see map).[4. The wall was built with American, French, and Spanish funding. Its purpose was to stall the conflict and to militarily exhaust the Polisario Front, preventing incursions into the territory and radically severing ties between combatants and the populations of cities of the occupied Sahara.] Worn down from years of fighting, the two sides were ultimately forced to negotiate, and the conflict ended without a clear winner.

Second Phase: Peace Plans and Diplomatic Stalemate

In 1991, Morocco and the Polisario signed a cease-fire and peace agreement under the supervision of the United Nations and the former Organisation of African Unity. This agreement opened the door for a referendum on self-determination for the Sahrawi, which was to be supervised by the United Nations Mission for the Referendum in Western Sahara (MINURSO). However, the January 1992 deadline for implementation was continually postponed.

Continuing violations of the cease-fire, government support for new civilian colonization of the disputed territory, and MINURSO’s lack of effectiveness resulted in the suspension of the peace plan in 1996. A year later UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan and the new special envoy for the Sahara, former U.S. Secretary of State James Baker, relaunched the process through the Houston Agreement, which was rejected by Morocco. Baker then designed a new strategy that led to two more unsuccessful plans. The Baker Plan I (2001) was rejected by the Polisario Front, and the Baker Plan II (2003) was rejected by Morocco. The Moroccan government’s rejection of Baker II, and its declaration that it would only accept a solution that secured autonomy for the Saharan territory circumscribed within Moroccan sovereignty, caused Baker to resign in 2004.[5. For more on the second stage of diplomatic negotiations, see Martine de Froberville, Sahara Occidental: La confiance perdue (Paris: L’Harmattan, 1996); and Carlos Fernandez Arias, “Western Sahara: One Year after Baker,” Foreign Policy, no. 107 (2005).]

Third Phase: Increased Tensions and Transformations in Sahrawi Society

In 2005 Kofi Annan appointed a new special envoy, Peter van Walsum, who sought to jump-start the stalled process. Following UN Security Council Resolution 1754 of 2007, representatives of the two parties held face-to-face negotiations in Manhasset, New York, but these meetings only confirmed the apparent impossibility of reconciliation between the Polisario Front and the Moroccan government. This lack of consensus led in 2008 to the departure of Van Walsum, who was replaced the following year by the U.S. diplomat Christopher Ross. Ross had some success in rebalancing the position of the United Nations between the two contenders and led numerous rounds of negotiations in Manhasset between 2011 and 2013. However, the diplomatic venue had long since lost its effectiveness for resolving the conflict.

Even as negotiations continued after the collapse of Baker II, the conflict began to shift into a new phase characterized by a radicalization of the positions advocated by the Sahrawi civil population. This was evidenced in the occupied territories by clashes and riots of varying intensity, including the intifada[6. The Sahrawi borrow the term from the Palestinians to refer to manifestations of resistance against occupation and the living conditions of the Sahrawi people: repression, lack of access to basic services, discrimination, high unemployment, exploitation of natural resources, and the like.] of 2005 and the uprising in Gdeim Izik in October 2010. In recent years the situation has not changed significantly in the occupied territories, where repression and discrimination against the Sahrawi population continues to produce cyclical violence and forced displacement. Increasing unrest has also been visible within the camps, especially among youth. Some demand a renewal of armed conflict and a greater role in the decision-making process; others seek primarily to improve their living conditions.

Sahrawi youth. Photo credit: European Commission DG ECHO via Flickr.

Sahrawi youth. Photo credit: European Commission DG ECHO via Flickr.

After so many years of what was supposed to have been a “temporary solution,” the talk about durable solutions outside Tindouf, as discussed by the United Nations, is at present a chimera. Over the decades the situation in the occupied territories has become extremely complex due to the profound transformation of the territory and the composition of the population under the jurisdiction of the Moroccan state. This has transformed the Sahrawi into a minority in their own land and has greatly hindered the process of their repatriation from the refugee camps.[7. The Sahrawi may make up as little as 20 percent of the population currently living in Western Sahara. Yolanda Sobero, Sahara: Memoria y Olvido (Barcelona: Ediciones Planeta, 2010).] In parallel, there have been profound changes in the camps themselves related to the introduction of a market economy, the weakening of the Sahrawi ideological revolutionary goals, and increased migration to Spain.[8. For more information on the third phase of the conflict in Western Sahara, see Sobero, Sahara; and Carmen Gómez Martín, “Sahara Occidental: Quel scénario après Gdeim Izik?” L’Année du Maghreb VIII (2012).] Further developments followed the death in 2016 of the historic Polisario leader Mohamed Abdelaziz, president of the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic since 1976. The new Sahrawi president, Brahim Ghali, has demonstrated a more combative attitude, including through the movement of troops and armaments to the Moroccan separation wall, reviving former tensions and placating the more aggressive segment of the Sahrawi youth.

Tindouf Camps: Imprisoned in the Algerian Hamada[9. The camps are located in the Draa Hamada, a stony desert formed by rocky plateaus.]

The state-like administrative structure of the Sahrawi refugee camps makes them comparable only to the Palestinian case. The camps are divided into four villages with a single “politico-administrative” center in Rabuni, where the Sahrawi government administers warehouses of food provided by international aid.[10. In recent years, another camp has been forming around the “February 27 School,” one of the leading schools for girls.] The four villages are called wilayas (provinces) and take the names of the main cities of Western Sahara: Laayoune, Smara, Dakhla, and Auserd.[11. There is a distance of between 20 and 60 kilometers between each wilaya, except Dakhla, which is 200 kilometers from other sites. The airport in the Algerian city of Tindouf is between 20 and 50 kilometers from the administrative center of Rabuni, the camp of Laayoune, and the camp of Smara.] Each wilaya is divided in turn into daïras (municipalities), which also bear the names of landmarks of Western Sahara. Finally, each daïra is divided into several neighborhoods called hayys.

Until the mid-1990s the camps were entirely dependent on humanitarian assistance provided by UNHCR, the World Food Programme (WFP), the Humanitarian Aid Office of the European Union, the Spanish Agency for International Cooperation, and the Algerian state. Additionally, NGOs and associations of European (mainly Spanish, Italian, and French) solidarity have cooperatively carried out a number of development projects. Over the years this group of organizations has been responsible for supplying the camps with infrastructure; transport and communication networks; fuel storage and distribution; water wells; women’s centers; schools, clinics, and hospitals; agriculture and irrigation projects; and the training of health and education personnel, among other provisions.[12. Carmen Gómez Martín, La migracion saharui en España: Estrategias de visibilidad en el tercer tiempo del exilio (Saarbrücken, Germany: Editorial Académia Española, 2011).] Despite this financial and material support, however, the food supply in these camps is insecure.[13. According to a 2008 report by Doctors of the World, UNHCR, and the World Food Programme, malnutrition in the camps affects 61 percent of children and 55 percent of women. The report noted that the recommended number of kilocalories a person should consume per day is between 1,200 and 1,500. In the Sahrawi camps, it stood at 698 kilocalories per day and only reached 800 kilocalories per day when supplemented with goat or camel meat. See Irene Pérez Alcalá, “Estado nutricional y salud reproductora de la mujer saharaui,” in Cristina Bernis Carro, María Rosario López Giménez, and Pilar Montero López, eds., Determinantes biológicos y sociales de la maternidad en el siglo XXI: Mitos y realidades (Madrid: IUEM-UAM, 2009), pp. 231-48.] This is due to changes in the priorities of the international humanitarian organizations supporting the camps, as well as to the fact that there is no official census of the camps, and these various organizations use significantly different figures for the number of refugees living in the camps at any given time, varying widely between 90,000 and 165,000.[14. Carmen Gómez Martín, “Saharauis: Una migración circular entre España y los campamentos de refugiados de Tinduf,” in Carlos de Castro et al., eds., Mediterráneo migrante: Tres décadas de flujos migratorios (Murcia: Ediciones de la Universidad de Murcia, 2010).]

Mohamed Embarek Saleh Deihan selling herbal medicines at Dakhla, 2007. Photo credit: Yerbero farmaceutico Dakhla via Flickr.

Mohamed Embarek Saleh Deihan selling herbal medicines at Dakhla, 2007. Photo credit: Yerbero farmaceutico Dakhla via Flickr.

As in many refugee camps in Africa, the Middle East, and Asia, the transformation of these spaces of “temporary shelter” into places of long-term settlement has given rise to a complex economic system.[15. Eric Werker, “Refugee Camp Economies,” Journal of Refugee Studies 20, no. 3 (2007), pp. 461-80.] In the Sahrawi case, capital inflows are mainly produced in two ways. One is by remittances from migrants, which has allowed access not only to basic necessities but also to such goods as televisions, computers, mobile phones, and even old all-terrain vehicles. The other source is an informal economy centered around smuggling goods, such as food, clothing, tobacco, and even cars and trucks across the permeable Mauritanian and Algerian borders.[16. Sophie Caratini, “La prison du temps. Les mutations sociales à l’œuvre dans les camps de réfugiés sahraouis. Deuxième partie: L’impasse,” Afrique Contemporaine 222, no. 2 (2007), pp. 181–97.] Additionally, a small amount of trade occurs between the camps and the border cities of these two countries, which has allowed for the formation of small food, clothing, and sundry shops, along with call centers and workshops.[17. Gómez Martin, “Saharauis: Una migración circular.”] The development of a monetary economy has also led to the establishment of some business enterprises that employ taxi drivers, mechanics, masons, carpenters, bakers, and butchers.

As Eric Werker has noted, the main economic actors in any camps are the refugees themselves, many of whom possess skills and access to networks and commercial capital acquired either before or during their residence in a camp.[18. Werker, “Refugee Camp Economies.”] Thus, the above picture challenges the normal conception of refugee camps as places of stasis, and of refugees as passive, paralyzed victims who are totally dependent on international aid.

Refugee Camps as a Durable Solution?

The case of the Sahrawi camps is a clear example of how a temporary protective situation may become permanent. This raises the question of whether a refugee camp can or should be seen as a lasting and just solution, especially for those who are the victims of state conflicts. For some years there have been debates within academia and international organizations around the question of how long a person should be allowed to remain a refugee, but all would likely agree that refugee status should not be unending. The United Nations offers three types of so-called durable solutions: voluntary repatriation, local integration, and resettlement in a third-party country. All three are intended to “eliminate the objective need for refugee status and to allow refugees to acquire or reacquire the full protection of a state.”[19. UNHCR, “Informe: Tendencias globales,” Oficina del Alto Comisionado de las Naciones Unidas para los Refugiado, 2012a, p. 12.]

Here we should make a distinction between those who obtained refugee status through an individual application and those cases of prima facie refugees (a collective and temporary category of protection), who usually end up grouped in camps in international border areas. The durable solutions recommended by the United Nations differ for the two groups. Individual applicants are the more common cases in developed countries because it is obviously easier for a host state to integrate an individual rather than large masses of refugees, and because individual applicants have more guarantees than prima facie refugees, particularly in the local integration process and, to a lesser degree, for resettlement in third countries or voluntary repatriation. For prima facie refugees, voluntary repatriation is more commonly recommended by the United Nations. This solution, however, requires the resolution of the conflict that caused the forced displacement in the first place. Unfortunately, such resolution rarely happens and, as we will see below, the practical outcome in this scenario is a prolonged stay in a refugee camp.

Of the three solutions, voluntary repatriation is the one most often sought by any government that receives refugees in need of international protection. Both the 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees and the African Declaration of 1969 propose repatriation once the original causes of flight have been resolved. The problem with this recommendation is that the “resolution” of the initial conflict often becomes an automatic trigger for repatriation, even when—as is often the case—the situation still remains dangerous or unstable.[20. Some seven million refugees have returned to their home countries over the past ten years. However, as UNHCR itself points out, most cases occurred in countries of poor stability: Angola, Cameroon, Democratic Republic of Congo, Liberia, and Zambia. See UNHCR, “Informe: La situación de los refugiados en el mundo. En busca de la solidaridad,” Oficina del Alto Comisionado de las Naciones Unidas para los Refugiados, 2012b.] As an alternative solution, resettlement in a third country can sidestep this problem and is an exercise in shared responsibility. But that option benefits a very small number of refugees—usually less than 1 percent worldwide due to the lack of politically willing countries.[21. UNHCR, “Informe: Tendencias globales” (2012a).] Finally, there is local integration, which is the preferred option for most of the refugees themselves. It is a complex and gradual process that generally leads, first, to obtaining permanent residence rights and, eventually, to the acquisition of citizenship in the country of asylum. While this is, as noted, the refugees’ preferred option, there are several problems related to the difficulty of measuring its impact; and countries accepting refugees seldom abide by international law prohibiting the discrimination against and exploitation of refugees.[22. UNHCR, “Informe: La situación de los refugiados en el mundo” (2012b).]

In the case of the refugee camps themselves, there is a fundamental disagreement about whether these spaces should exist at all. Some authors, such as Richard Black, argue that their total disappearance would give way to forms of self-settlement and integration within local communities in the host countries, aided by government programs and international agencies.[23. Richard Black, “Refugee Camps Not Really Reconsidered: Response by Richard Black,” Forced Migration Review 3, Debate (1998).] Others, such as Jeff Crisp and Karen Jacobsen, argue that the camps should be maintained but with changes. This argument is based on the assertion of Gaim Kibreab that border camps remain the preferred choice for governments—not out of humanitarian concern, but for reasons of control. They prevent local integration of the refugee population, enable easier repatriation to the countries of origin, and attract international assistance through the visibility of the camps.[24.Cited in Jeff Crisp and Karen Jacobsen, “Refugee Camps Reconsidered,” Forced Migration Review 3, Debate (1998).]

As an emergency humanitarian solution, refugee camps will no doubt continue to exist. However, a framework needs to be implemented that substantially improves living conditions and provides inhabitants not only with protection but also with basic rights. According to Crisp and Jacobsen, this would entail four main goals: (1) converting the camps into more manageable, autonomous, and self-sufficient structures (similar to small towns); (2) avoiding the establishment of camps in unstable places that may increase the lack of security, such as near international borders; (3) creating and managing camps in a way that causes the least possible impact with respect to the natural and social environment; and (4) allowing refugees to have greater freedom of movement and opportunities for work.[25. Ibid., p. 28.] In short, refugee camps should become more livable, dignified, and safe.

However, even if one were to accept the idea of reforming the camps as the best alternative, there would still be a problem of a higher order. Better conditions do not mean the end of the problem of uncertain status or long-term residence in the camps. This leads us to the second part of the debate. The protection that refugee camps supposedly provide highlights an important contradiction between the claims of international organizations and the everyday reality in most refugee camps. The United Nations itself does not consider the transformation of refugee camps into permanent spaces of settlement, no matter how well done, as a lasting and just solution. Nonetheless, stated policy aside, some of these camps that become long-term settlements are converted into places with permanent structures that are welcoming to diverse populations, depending on the conflict.[26. This is the case of the Dadaab camp in northern Kenya. It was established by UNHCR to collect Somali refugees after the fall of Mogadishu in 1991, but as the years went on it welcomed a mixed population, composed mostly of Sudanese, Somalis, Ethiopians, Ugandans, and Rwandans. See Marc-Antoine Perouse de Montclos and Peter Mwangi Kagwanja, “Refugee Camps or Cities? The Socio-economic Dynamics of the Dadaab and Kakuma Camps in Northern Kenya,” Journal of Refugee Studies 13, no. 2 (2000), pp. 205–22.] Thus, while they may still be referred to as temporary solutions in the discourse of international organizations, in practice their characteristics and their own dynamism makes them permanent. Continued acceptance of this contradiction is a serious problem, because it condemns the residents to isolation, and it deprives them of the exercise of the fundamental rights of citizenship, including the right to free movement. Moreover, they can be forced into a situation of legal uncertainty, which in many cases leads to statelessness, which in turn, as in the Sahrawi case, implies a total loss of citizenship rights.[27. Two facts help explain this situation. The population fled the Spanish Sahara in 1975–1976 and lost Spanish nationality through the application of Royal Decree 2258 of August 10, 1976. Moreover, the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic has never been recognized internationally; consequently, Saharan nationality is not accepted. As a result, much of the population living in the camps has been condemned to statelessness.]

Contradictions of the Model in Protracted Refugee Situations

Many refugee camps, especially those found on the African continent, have become permanent, equipped with an increasingly developed infrastructure. In this sense, urbanization becomes a natural consequence of waiting a long time for relocation while needing to provide services to an ever-increasing population facing obvious shortages. It is also a consequence of the entry, albeit erratically, of capital and the subsequent boosting of a camp’s economy. One associated problem of this growing economy is that the circulation and possession of money contributes to significant social inequalities among the refugees, given that not all have additional resources to purchase goods or generate a “business.” Another is that the passing of time and the rising inequalities plague the younger population in particular, many of whom are born within the camps themselves.

The Sahrawi camps are no different in these regards. They exhibit the partial urbanization discussed above, with the appearance of houses, roads, shops, health and educational infrastructure, and the like.[28. Montclos and Kagwanja, “Refugee Camps or Cities?”] Such urbanization is a manifestation of the contradiction discussed in the previous section. The situation of the Sahrawi is unique, however, since the Sahrawi camps contain a state in exile with a political and administrative center in Rabuni. This indicates that these spaces have the potential to be transformed into political and institutional structures within a concrete state project.[29. Randa Farah, “Refugee Camps in the Palestinian and Sahrawi National Liberation Movements: A Comparative Perspective,” Journal of Palestine Studies 38, no. 2 (2009).]

Within the Sahrawi camps there is also a marked contrast between those who are able to “improve” their living conditions and those who cannot supplement humanitarian aid with products from other sources of income. Moreover, the emergence of inequality in the possession of material goods has led to certain changes in the customs of the Sahrawi people, who traditionally bartered and exercised collective solidarity. The emergence of a sense of ownership and the protection of acquired assets are evidence of this phenomenon. The construction of houses of adobe brick next to the traditional jaimas.[30. Tents made of leather and used by the nomadic peoples of the desert.] the building of walls to create a closed perimeter around the home, and the closure of doors at night or whenever the occupants are away all represent a documented cultural change— evidence of a previously nonexistent distrust.

In addition, the current situation in the Sahrawi camps is undoubtedly a delicate one since most of the refugees’ problems—such as social inequality, unemployment, frustration with the lack of future prospects and material possessions, economic dependence, and submission to the old political elites—are linked to the exercise of the rights of citizenship. These especially affect the very young who, through various experiences (for example, study programs or summer vacations in Latin American, Arab, and European countries), are aware of a life away from the inhospitable Draa Hamada. The impossibility or frustration of implementing a different future has led many Sahrawi youth to radicalize their behavior and ideas, not only with respect to the conflict but also in their everyday conduct. As such, they are putting increasing pressure on the Polisario Front to return to arms and are questioning the representativeness of the Sahrawi government.[31. Gómez Martín, La migración saharaui en España.] As indicated by several investigations carried out with young Sahrawi both inside the camps and in Spain, many also exhibit an apathy toward education and an obsession with material and monetary accumulation, which is the only element capable of supplanting the desire—inculcated from childhood—to return to an independent Western Sahara.[32.Carmen Gómez Martín and Cédric Omet, “Les ‘dissidences non dissidentes’ du Front Polisario dans les camps de réfugiés et la diaspora sahraouis,” L’Année du Maghreb V (2009), pp. 205–22; Alice Corbet, “Nés dans les camps: Changements identitaires de la nouvelle génération de réfugiés sahraouis et transformations des camps,” Thesis of Anthropology, 2008, Paris, EHESS.]

Many refugees in the Middle East and North Africa, both individually and collectively, have also taken a number of measures to avoid being trapped in these camps altogether. While not recognized as refugees, many people fleeing wars and conflicts prefer to settle in cities, where they have more freedom of choice, movement, and human rights, since refugee status no longer guarantees these protections. For these reasons, over the last two decades many Sahrawi have left the camps and relocated themselves in Algeria, Mauritania, and even Spain—even if these measures involve changing their status from refugee to migrant.

The Challenges of the Sahrawi Case Regarding Durable Solutions

Two of the three solutions proposed by UNHCR are widely accepted by the international community as desirable outcomes: voluntary repatriation and local integration. These solutions are connected to more comprehensive strategies aimed at consolidating peace processes and development in post-conflict countries or in situations of high political instability.[33. UNHCR, “Informe: Tendencias globales” (2012a), p. 13.] However, we cannot speak of long-term solutions in the same sense for the Sahrawi. The contexts differ too much due to the extreme prolongation of the conflict and the many political, social, and economic transformations that have taken place over the last four decades in the camps and in the occupied territories. It is therefore difficult to apply comprehensive strategies that jointly value the classical durable solutions and the consolidation of peace processes when the root causes of the conflict still exist, and when the circumstances of the confrontation have changed dramatically over time.

The establishment by the Polisario Front of refugee camps for the Sahrawi may have initially been a wise decision, but it has clearly failed the Sahrawi people in the long term. Moreover, it is impossible to determine how long Algeria will continue to allow a state-in-exile within its territory. So far this has never been questioned, but no state is immune from experiencing transformations driven by internal and external political changes (we only have to look at the changes brought about by the Arab Spring). Further, we cannot predict the effects that restlessness may have on the youth in these camps, nor can we predict the effect of the violence suffered by Sahrawi on the other side of the retaining wall that separates the occupied territories from those controlled by the Polisario Front.

Under these circumstances talk of resettlement, voluntary return, or local integration is far from a reality for the Sahrawi. The evolution of the conflict has continued to stymie all international proposals to resolve it. For example, the self-determination referendum advocated by the Polisario Front and supported by international law in 1991 would have permitted the Sahrawi to return to an independent Western Sahara. Unfortunately, this solution has been blocked because the population of the major Saharan cities has become majority Moroccan and because the Alaouite Moroccan state has refused to accept the referendum while still imposing de facto control over the territory.

A Third Way?

A third way—known as the “autonomy project” (so named by Bernabé López García and Miguel Hernando de Larramendi)—has been gaining some favor in recent years.[34. See Bernabé López García, “Iniciativas de negociación en el Sáhara Occidental: Historia de la búsqueda de una ‘solución política,’” ARI, no. 85 (2007); and Miguel Hernando de Larramendi, “La cuestión del Sáhara Occidental como factor de impulso del proceso de descentralización marroquí,” Revista de Estudios Internacionales Mediterráneos, no. 9 (2010), pp. 132–41.] This solution, supported by Morocco, consists of a system of political and administrative autonomy for Western Sahara under Moroccan control that could promote the voluntary return and reintegration of Sahrawi from the camps to the occupied areas. However, both López García and Hernando de Larramendi agree that without the democratization of the Moroccan state the decentralizing step is also unlikely to occur. Further, the strained coexistence between the Sahrawi population and the Moroccan settlers in the occupied territories adds another layer of difficulty. The arrival and integration of the camps’ population would stoke the fire that already exists between these two populations. Thus, this solution seems entirely inconceivable today.

A Sahrawi man holding the flag of the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic, a partially-recognized state proclaimed by Polisario in 1976. Photo credit: Michele Benericetti via Wikimedia Commons.

A Sahrawi man holding the flag of the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic, a partially-recognized state proclaimed by Polisario in 1976. Photo credit: Michele Benericetti via Wikimedia Commons.

There is another option that has not been widely promoted but that could have a significant impact, especially for the refugees whose status it would change. It is the well-known aspiration of the Polisario Front to transform Tifariti, the “capital” of the “liberated territories,” to a habitable place where refugees from the camps could be transferred. This seems both a plausible and more beneficial solution to the interests of the population, enabling real and voluntary return to Sahrawi territory. However, two obstacles hinder this possibility. First, the liberated territories consist of a small strip of arid land that barely covers a third of the territory of Western Sahara and contains few natural resources. This alone, however, is not an absolutely insurmountable obstacle, as several hundred Sahrawis have been able to live in this territory—mainly military personnel and a population that has continued to maintain the Bedouin lifestyle. The second and larger problem, however, is that Tifariti is located only a few kilometers from the defensive wall that acts as a border with the occupied territories. Thus, the movement of refugees to this area could lead to a revival of war. In addition, this solution would likely be rejected by the international community because this strip is considered a no man’s land. This option has therefore not been entertained as a possibility by the United Nations or the countries participating in diplomatic discussions to resolve the conflict (France, Spain, and the United States).

To date, the balance sheet for the performance of international actors on this issue (like MINURSO and the various UN special envoys) is in the negative. In many cases these parties have not maintained neutrality, and they do not recognize the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic as an independent state. Further, they have not resolved ownership of this strip of territory, which is a major impediment to a transfer of the population. Without the true possibility of ending the political stalemate, any of the three durable solutions will lack practical application. Consequently, the refugee camps remain the only plausible solution to the present situation, although they are not recognized as an acceptable solution by most of the political actors involved in the stalemate.

Conclusion

A large number of the Sahrawi continue to live in refugee camps in the absence of any new proposal for resolving the prolonged conflict that fits the United Nations’ classic trio of durable solutions: resettlement, return, or integration. An examination of the plight of the Sahrawi seems to confirm the veiled acceptance by the international community and UNHCR that refugee camps are the only solution in the absence of a political settlement. Further, the difficulty confronting the Sahrawi situation can be extrapolated to several other regions where there are conflicts beset by stalemates lasting years and even decades, such as the Palestinian, Sudanese, and Congolese cases.

The contradiction between discourse and practice places refugee populations in a situation of significant and sustained loss of rights. Among these are the inability to access decent housing and education and to exercise political and social rights, including the rights to work and to free movement. In sum, refugee camps seem to have become a medium that allows the international community to stall when it lacks the ability to resolve conflict; and in some cases they are also a means to contain large and unwelcome migration to other countries, especially those in the North.[35. B. S. Chimni, “The Birth of a ‘Discipline’: From Refugee to Forced Migration Studies,” Journal of Refugee Studies 22, no. 1 (2009), pp. 11–29.]

If, as is likely the case, these types of camps will remain de facto long-term (rather than durable) solutions, international actors must take steps to ensure that appropriate conditions exist to accommodate these vulnerable populations. First and foremost they must provide immediate protection and basic services. But the camps must also be viewed as a transitional measure that will help facilitate the mechanisms for voluntary return, resettlement, or integration depending on the context and the needs of populations. If this does not occur, there is a risk of transforming the camps into cities without citizens. The result will be more impoverished urban spaces with precarious and insecure pockets of disenfranchised populations.

*Editor’s note: This original essay was translated from Spanish by Maria Codina, with the assistance of Drew Thompson. The editors also wish to acknowledge the contribution of Prof. Joy Gordon, Ignacio Ellacuria, S.J. Chair in Social Ethics at Loyola University-Chicago, without whose initiative and support the publication of this essay would not have been possible.

A PDF version of this essay is available to subscribers. Click here for access.

More in this issue

Spring 2017 (31.1) • Essay

Heeding the Clarion Call in the Americas: The Quest to End Statelessness

In 2014, the office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees launched the #IBelong Campaign to eradicate statelessness by 2024. Given that UN Secretary-General António ...

Spring 2017 (31.1) • Feature

Shame on EU? Europe, RtoP, and the Politics of Refugee Protection

In this feature, Dan Bulley argues that there is little to be gained by invoking the RtoP norm in the context of the refugee crisis. ...