Editors' note: For more on this topic, you can listen to our interview with Ayelet Shachar by clicking here.

Tough action and rhetoric are the stamp of U.S. President Donald Trump’s immigration policy. The decision in September 2017 to revoke the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA)—a program that shields young undocumented immigrants (“Dreamers”) from removal, granting them an opportunity to complete school, enroll in college, volunteer for the armed services, or join the workforce—proved to be the most contentious in a groundswell of executive orders, directives, memos, and wide-ranging enforcement efforts to curtail unauthorized presence.[1. These measures include the introduction of Executive Order No. 13767 of January 25, 2017, “Border Security and Immigration Enforcement Improvements,” Federal Register 82, no. 18, p. 8793; and Executive Order No. 13768 of January 25, 2017, “Enhancing Public Safety in the Interior of the United States,” Federal Register 82, no. 18, p. 8799. Memorandum from John Kelly, Secretary of Homeland Security, to Kevin McAleenan, Acting Commissioner, U.S. Customs and Border Protection et al., “Implementing the President’s Border Security and Immigration Enforcement Improvements Policies” (February 20, 2017). The decision to rescind DACA was announced on September 5, 2017. In early 2018, DACA recipients were awarded an injunction from a federal court that temporarily halts the rescinding of the program. As of mid-January, there were negotiations underway in Congress to reach an agreement on the future of the DACA program.] Critics describe such sweeping measures as amounting to an anti-immigrant crusade. Supporters, meanwhile, applaud them as taking the handcuffs off immigration enforcement officers and border patrol agents. With the rising tide of restrictionism and the government’s tough-on-immigration approach under the rubric of a “nation of laws,” it is easy to lose sight of the only immigration program that has been renewed and extended under the Trump administration: the EB-5 program, or the “golden visa.”[2. On the competing visions of a nation of immigrants and that of a nation of laws, see Ayelet Shachar, “Earned Citizenship: Property Lessons for Immigration Reform,” Yale Journal of Law & the Humanities 23, no. 1 (2011), pp. 110–58.]

In 2017 the president signed into law and renewed the extension of the EB-5 program, which offers the world’s wealthy a coveted path to securing lawful permanent residence (LPR) status, jumping the queue and gaining an easy pass through the otherwise increasingly bolted gates of admission. The price tag for securing a green card via the EB-5 program ranges from $1 million to a “discounted” rate of $500,000 if funds are for specially designated rural areas or areas of high unemployment.[3. U.S. Department of Homeland Security, U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, EB-5 Immigrant Investor Program, www.uscis.gov/working-united-states/permanent-workers/employment-based-immigration-fifth-preference-eb-5/about-eb-5-visa-classification.] The American golden visa, like comparable schemes in other desirable destination countries, caters to the global 1 percent. It treats money transfers—in large quantities—as a currency for acquiring entry visas, residence permits, and, ultimately, citizenship itself.

The contrast between the DACA “Dreamers” and the EB-5 “Parachuters” reveals the sharp edge, and deep injustices, of current policies.

Unlike the Dreamers, who now face the risk of deportation from the only country they have ever known as home, these visa applicants have no prior “bona fide relationship with a person or entity in the United States.”[4. The bona fide formulation is drawn from the recent U.S. Supreme Court decision in the travel ban case. See Trump v. International Refugee Assistance Project (IRAP), 582 U. S. ____ (2017).] Instead, they gain a privileged route to enter the United States and remain lawfully in the country based on their ability to transfer capital across borders. The contrast between the DACA “Dreamers” and the EB-5 “Parachuters” reveals the sharp edge, and deep injustices, of current policies. The former have already become part of the fabric of the United States—including its society and economy—through their ongoing, peaceful, and productive presence, yet the sword of deportation continues to hang over their heads. On the other hand, the latter benefit from expedited and simplified pathways to obtain full-fledged legal membership, even if they fail to establish any tangible connections to their new home country.

The United States is not alone in testing, blurring, and eroding the state-market boundary regulating access to membership. A growing number of countries are putting their visas and passports up for sale. The proliferation of these programs is one of the most significant developments in citizenship and immigration practice in the past few decades, yet it has received scant attention in the literature. In the following pages, I begin to address this lacuna by identifying the core legal and normative puzzles associated with this new trend, which I will refer to as the marketization of citizenship to highlight a dual transformation: the commodifying of access to membership and the hollowing out of the “status, rights, and identity” components of citizenship.[5. These multiple facets of citizenship are captured well by Christian Joppke, “Transformation of Citizenship: Status, Rights, Identity,” Citizenship Studies 11, no. 1 (2007), pp. 37–48.] Marketization is never merely an economic process; it is also deeply political, as it reshapes and reengineers the boundaries of and interactions between states and markets, voice and power, the inviolable and the mercantile.

The intrusion of market logic into the sovereign act of defining “who belongs” raises significant justice and equality concerns that require closer scrutiny.

The intrusion of market logic into the sovereign act of defining “who belongs” raises significant justice and equality concerns that require closer scrutiny, both empirical and normative—the remit of this essay. I treat these new developments as a productive site to explore foundational questions about the character of citizenship and its transformation in today’s world. I begin by tracing the global surge in the marketization of citizenship, providing illustrative examples, before turning to explore the official rationales for the EB-5 and exposing their shortcomings. Moving from the positive to the normative, I develop several lines of critique that seek to show that this new trend is uniquely threatening to notions of citizenship reflecting the horizon of equality and participation, regardless of which theories of state and society—liberal, civic republican, or democratic—inform them.

The Golden Visa: Diachronic and Comparative Insights

It is useful to begin by stepping back and taking in a broader comparative perspective. In the United Kingdom the “Tier 1” investor visa requires a minimum of £2 million to establish a leave to remain (the greater the investment, the shorter the wait time). In Australia the “significant investor” visa is open to those who are willing to invest more than AU$5 million, while the super wealthy can apply for a “premium” visa that will fast-track them to residency within twelve months in exchange for the whopping sum of AU$15 million. Portugal’s golden visa program grants residency to global investors in exchange for property or capital investments, coupled with “extremely reduced minimum stay requirements.”[6. “Golden Visa Portugal–Residency for Investors” (online), goldenvisa-portugal.com/FAQ.html.] Malta, the smallest member state of the European Union, has gone a step further, putting its passport up for sale in exchange for a donation or investment of €1.15 million, opening a gilded backdoor to European citizenship. Wealthy purchasers can acquire “passports of convenience” from the islands of the Caribbean and the Pacific without having to inhabit, or even visit, the passport-issuing country.[7. States are not a

lone in charting this new terrain. Intermediaries, both local and transnational, such as specialized law firms, wealth mangers, and other for-profit third parties have also exerted influence in shaping and transplanting such programs from one country, or region, to another.]

Valletta, Republic of Malta. Malta's Individual Investor Program offers citizenship in exchange for an investment of approximately €1.15 million, plus residency requirements. Photo Credit: Joshua Zader via Flickr.

Valletta, Republic of Malta. Malta's Individual Investor Program offers citizenship in exchange for an investment of approximately €1.15 million, plus residency requirements. Photo Credit: Joshua Zader via Flickr.

The United States is not alone in testing, blurring, and eroding the state-market boundary regulating access to membership.

While the details of the various programs vary, they all rely on a shared premise: allowing the über-rich, even those with only tenuous ties to the passport-issuing country, the opportunity to acquire citizenship based on the heft of their wallets, bypassing standard residency, linguistic proficiency, and related civic-integration requirements that states otherwise vigorously enforce.[8. For a comparative overview of these civic-integration requirements, see Sara Wallace Goodman, Immigration and Membership Politics in Western Europe (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014).]

Not long ago, the market catering to wealthy purchasers seeking passports of convenience was primarily associated with unscrupulous offshore tax havens in microstates in the Pacific and the Caribbean. Many such programs, which began to emerge in the 1980s, were shut down after they became associated with fraud, corruption, and money laundering.[9. Anthony van Fossen, “Citizenship for Sale: Passports of Convenience from Pacific Island Tax Havens,” Commonwealth & Comparative Politics 45, no. 2 (2007), pp. 138–63.] Lenient due diligence and background review procedures made these programs vulnerable to abuse; and here again applicants did not need to even set foot in the passport-issuing country. For those seeking a second or third passport, such programs offered significant tax advantages and facilitated visa-free travel; passport holders could also elude stricter financial record-keeping and reporting requirements in their home countries.

These programs gained some degree of saliency when Canada became the first major destination country to introduce its immigrant investor route in 1986. The American EB-5 visa was launched soon thereafter in 1990. In a classic example of trans-jurisdictional “borrowing,” other leading immigrant-receiving countries, including Australia, New Zealand, and the United Kingdom, quickly established their own variants of preferred admission routes for the rich. Before its termination in 2014, the Canadian program went through several changes, mostly upping the price requirements, but it remained one of the most popular among the world’s affluent. When it was ultimately shut down, the program had a wait list of over 40,000 applicants.

Today, it is Europe—the progenitor of modern statehood and the contemporary inventor and facilitator of the world’s most comprehensive model of supranational citizenship—that is leading the trend toward pecuniary-centered membership transactions. The most recent data reveal that about “half of the member states have designated immigrant-investor routes.”[10. Madeleine Sumption and Kate Hooper, Selling Visas and Citizenship: Policy Questions from the Global Boom in Investor Immigration (Washington, D.C.: Migration Policy Institute, 2014), p. 2.] Of these countries, some offer fast-tracked entry visas, many of which allow for later application for permanent residence, while others offer easier access or direct access to golden visas or permanent residence status.[11. Spain and Portugal are prime examples.] Yet others have gone further, offering express access to citizenship for direct cash transfers.[12. Malta’s initial legislation, adopted in 2013, in essence brought to the continent the Caribbean cash-for-passport model. Cyprus soon followed suit with its citizenship by investment program. In exchange for €2 million, Cypriot (and by extension European) citizenship can be acquired at an unprecedented speed—within three months—through naturalization by exception. See “Cyprus: Citizenship by Investment Program,” www.investcyprus.eu/.] So much for the International Court of Justice conclusion in the influential Nottebohm Case that "real and effective" ties between the individual and the state must underpin the conferral of citizenship.[13. The “real and effective” standard is applied in many jurisdictions, affirming a notion of citizenship as social membership; it is most famously drawn from the Nottebohm Case. See Nottebohm Case (Liechtenstein v. Guatemala), Second Phase, Judgment of April 6, 1955: I.C.J. Reports 1955, p. 22. This decision focused on the claims for diplomatic protection and recognition of citizenship by other members of the international community.]

The EB-5: Official Rationales and Their Limitations

Looking again at the United States, it is instructive to explore the official rationale for adopting the golden visa program and to assess its validity. The EB-5 program was originally intended to “stimulate the U.S. economy through job creation and capital investment by foreign investors,” especially in rural and high unemployment areas.[14. U.S. Department of Homeland Security, U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, EB-5 Immigrant Investor Program, www.uscis.gov/eb-5.] It has been controversial from the start. Federal regulators have repeatedly criticized the program for lack of sufficient safeguards to avert fraud, money laundering, and security risks. Recent studies have concluded that the government “cannot demonstrate that the program is improving the U.S. economy and creating jobs for U.S. citizens.”[15. Department of Homeland Security, Office of Inspector General, “United States Citizenship and Immigration Services’ Employment-Based Fifth Preference (EB-5) Regional Center Program,” Washington, D.C., December 12, 2013 (OIG-14-19), p. 5, www.oig.dhs.gov/assets/Mgmt/2014/OIG_14-19_Dec13.pdf.]

In the same vein, a comprehensive review of Canada’s investor-visa program found it beset by high regulatory costs and to be economically inefficient. The Canadian government disclosed that there was “little evidence that immigrant investors . . . are maintaining ties to Canada or making a positive economic contribution to the country.”[16. Government of Canada, Department of Finance, “The Road to Balance: Creating Jobs and Opportunities,” February 11, 2014 (F1-23/3-2014E), p. 81.] Scholars studying the patterns of transnational mobility of golden visa recipients have documented that once applicants receive permanent residence or a passport in their destination of choice, they do not display much of a connection to their new home countries.[17. For a thorough account, see David Ley, Millionaire Migrants: Trans-Pacific Life Lines (Malden, Mass.: Wiley-Blackwell, 2010).] This may help explain why the expectation that these “high value” migrants will provide net economic gains to the recipient society often goes unfulfilled. Longitudinal data from Canada, which at nearly three decades had the longest running investor program to date, reveal that “immigrant investors report employment and investment income below Canadian averages and pay significantly lower taxes over a lifetime.”[18. Government of Canada, Department of Finance, “The Road to Balance,” p. 81.] Keeping this empirical evidence in sight is important, as it assists in countering the assertion, “strongly [held] by law firms, accountants and consultancies that help organize the affairs of such investors,” that the marketization of citizenship trend is “self-evidently beneficial.”[19. Migration Advisory Committee, “The Economic Impact of the Tier 1 (Investor) Route,” (London: Migration Advisory Committee, 2013), p. 1.] As the United Kingdom Migration Advisory Committee (an independent nongovernmental think tank focusing on the economic benefits of migration) has concluded, “evidence rather than assertion” is required to establish that golden visa programs, in their varied forms, stand up to scrutiny.[20. Ibid., pp. 1–2 (emphasis added).]

The Canadian government disclosed that there was “little evidence that immigrant investors . . . are maintaining ties to Canada or making a positive economic contribution to the country.”

Although such evidence is wanting, the EB-5 program has seen a spike of applicants in recent years and is now routinely oversubscribed. Most U.S. golden visa recipients pay their way to the country by helping finance luxury real estate projects, a reality that has little to do with the stated justification for the program. As the Government Accountability Office notes, the EB-5 offers developers an auspicious opportunity to secure a “viable source of low-interest funding.”[21. U.S. Government Accountability Office, “Immigrant Investor Program: Progress Made to Detect and Prevent Fraud, but Additional Actions Could Further Agency Efforts,” Washington, D.C. (GAO-16-828), September 2016, p. 6. See also Eric Lipton and Jesse Drucker, “Kushner Family Stands to Gain from Visa Rules in Trump’s First Major Law,” New York Times, May 9, 2017, p. A1 (quoting Gary Friedland, a professor at NYU, who explains that traditional lenders for real estate projects can charge interest at 12 to 18 percent, whereas EB-5 loans carry a much lower interest, circa 4 percent, or roughly a third or a quarter of standard borrowing costs).] Thus, lower borrowing costs for ritzy projects are subsidized by international investors seeking a green card as reward. As critics have been quick to point out, the extension of the EB-5 program by Congress and the Trump administration serves the commercial interests of real estate moguls who are no strangers to the “first family and its rich and powerful friends.”[22. Editorial Board, “The Kushners and Their Golden Visas,” New York Times, May 9, 2017, p. A22.] Such intermingling of private interest with a quintessentially public act—determining whom to admit to the country and according to what criteria—casts a long shadow over the motivation for extending this program by an administration that has sown fear and trepidation among less-privileged categories of immigrants.

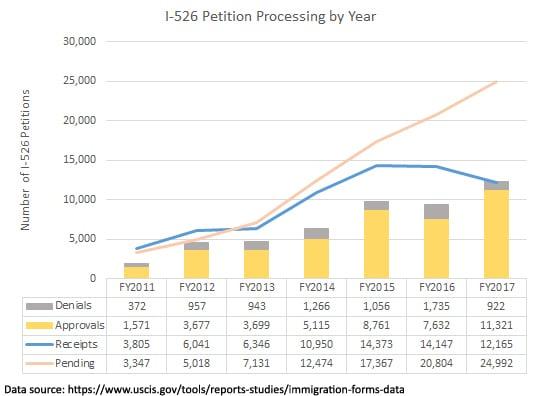

I-526 petitions, which are used to apply for the EB-5 visa, have been growing over the last decade. The United States caps the number of EB-5 visas at 10,000 per year. Credit: USCIS

I-526 petitions, which are used to apply for the EB-5 visa, have been growing over the last decade. The United States caps the number of EB-5 visas at 10,000 per year. Credit: USCIS

What Is Wrong with Commodifying Access to Membership?

Beyond the concerns already raised, at least three additional lines of critique can be advanced against putting visas and passports up for sale.[23. This section draws on arguments developed in greater detail in Ayelet Shachar, “Citizenship for Sale?” in Ayelet Shachar et al., eds., The Oxford Handbook of Citizenship (New York: Oxford University Press, 2017), pp. 789–816.] The tools of political and legal theory will prove useful as we undertake this task. A first argument is that of exacerbating inequality. It is a given that there exist high levels of wealth inequality throughout the world, enabling some individuals to think nothing of paying millions for a passport, while others can barely find the means to subsist. It should be clear that programs such as the golden visa exacerbate, rather than alleviate, the impact of such preexisting economic inequality by distorting the opportunity for individuals to gain access to membership in safer and more prosperous nations. And this is happening at the same time that restrictionism is on the rise globally. Across the world, millions seek refuge, taking increasingly desperate measures to reach a safe haven only to be met with refortified borders and evermore sophisticated legal rules and regulations to keep them out.[24. On such transformations, see Ayelet Shachar, The Shifting Border: Legal Cartographies of Migration and Mobility (Critical Powers Series, Manchester University Press, forthcoming 2018).] Thus we see that the replication and exacerbation of inequality fostered by these programs also serves to deepen global injustices.[25. I thank Sarah Fine for helpful conversations sharpening this point.]

Programs such as the golden visa exacerbate, rather than alleviate, the impact of preexisting economic inequality by distorting the opportunity for individuals to gain access to membership in safer and more prosperous nations.

The second set of concerns highlights the intrusion of the market into the political sphere, hitting at the heart of the sovereign act of delineating the contours of the demos. Not everyone objects to this development. Economists who view the market as the best locale for promoting individual choices and allocative efficiency without centralized control view this as a welcome advance. Indeed, the late Gary Becker famously endorsed what he termed “the economic approach to human behavior,” claiming that it should apply to “all human behavior” and “regardless of what goods are at stake.”[26. Gary S. Becker, The Economic Approach to Human Behavior (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1976), pp. 5, 8 (emphasis added).] On this rationale, nothing prohibits selling entry permits to the United States, a proposal that Becker made public in the op-ed pages of the Wall Street Journal the day after he won the Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences.[27. Gary S. Becker, “An Open Door for Immigrants—The Auction,” Wall Street Journal, October 14,1992, p. A1.]

As much as those holding a Beckerian line of argument would like to claim to the contrary, placing entry permits, residency cards, or citizenship up for sale is objectionable not merely because such proposals are novel and counterintuitive but for deeper and more profound reasons. Citizenship as we know it has—at least since the time of Aristotle—been comprised of political relations. As such, it is expected both to reflect and generate notions of participation, co-governance, risk sharing, and some measure of solidarity among those constituting the body politic. It is difficult to imagine how these democratic and reciprocal commitments can be preserved under circumstances in which insiders and outsiders are distinguished merely by their ability to pay a certain price. The objection here is to the notion that everything, including political membership, is commensurable and reducible to a dollar value.[28. For early and still influential critical accounts, see Margaret J. Radin, “Market-Inalienability,” Harvard Law Review 100, no. 8 (1987), pp. 1849–937; and Cass R. Sunstein, “Incommensurability and Valuation in Law,” Michigan Law Review 92, no. 4 (1994), pp. 849–50. See also Elizabeth Anderson, “The Ethical Limitations of Markets,” Economics & Philosophy 6, no. 2 (1990), pp. 179–205. Michael Walzer has influentially argued against allowing advantages in one social sphere or arena (the economic) to unfairly influence another (the political). See Michael Walzer, Spheres of Justice: A Defense of Pluralism and Equality (New York: Basic Books, 1983), pp. 95–103.]

When a stack of cash becomes the surrogate for membership, the basic connection between the individual and the political community is unfastened.

Furthermore, in establishing legal pathways to purchasing membership, the state is entering a high-stakes game that may ultimately undercut its own turf and legitimacy. The invisible hand may prove more efficient at developing mechanisms for trading or auctioning entry visas than those conceived by government lawyers and bureaucrats. Taking the commodification of citizenship scenario to its logical conclusion, one could imagine a full marketization scenario in which the state eventually prices itself out of the business of regulating. Private entities or membership trading corporations would determine the composition of the citizenry by setting different “membership tiers” according to the ability to pay, attaching variable levels of rights and protections as a matter of product differentiation.[29. Daniel M. Downes and Richard Janda, “Virtual Citizenship,” Canadian Journal of Law and Society 13, no. 2 (1998), p. 55.] It is unlikely that this scenario will materialize anytime soon (or ever) given the keen interest governments have in controlling and allocating membership goods—and the legacies of democratic and civil rights traditions of inclusion may offer fertile counter-narratives—but the conceptual shift in the perception of citizenship has already begun. And with this shift, a greater reliance on market mechanisms will deprive larger and larger portions of the world’s population from ever gaining a chance of access to citizenship in well-off polities.[30. This could also lead to tiered citizenship for present citizens. Marketization processes remind us of the long durée of history whereby the vast majority of the population was denied access to equal membership through mechanisms such as property ownership (over slaves, land, or household members) and the like.]

A third and closely related set of concerns speaks to the character of citizenship. When a stack of cash becomes the surrogate for membership, the basic connection between the individual and the political community is unfastened. Cash-for-membership programs detach the notion of citizenship from any meaningful kind of connection or nexus—be it extended residency, emotional attachment, or personal commitment—to the political community. This creates a dissonance with the familiar idea of citizenship as a valuable bond or relationship with a polity and its members.

While citizenship has been variously defined and has undergone many transformations, Rogers Smith observes that the “oldest, most basic, and most prevalent meaning is a certain sort of membership in a political community.”[31. Rogers Smith, “Citizenship: Political,” in Neil J. Smelser and Paul B. Baltes, eds., International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Studies (Oxford: Elsevier, 2001), p. 1857.] Although we know from the historical record that access to equal membership has never been open to all, this emancipatory and aspirational promise has gained tremendous staying power. While the scale and scope of the membership community has ranged from city-state to empire, citizenship has always been associated with political relations. The unique and reciprocal bond between the individual and the state (or other levels of government in multilevel conceptions of membership) distinguishes citizenship from traditional master/slave, emperor/subject, producer/consumer, or supply/demand relations of private provision. What changes about citizenship when it becomes the result of monetary exchange is not just the price tag of membership or the multitier paths to membership this creates but also its “character.” If political relations that are valued in part because they are not for sale become tradable and marketable, the ramifications may prove far-reaching, affecting not only those directly engaged in the transaction but also broader societal perceptions of how and why we value these relations.

I have elsewhere elaborated the jus nexi principle, accounting for the kinds of links and ties to a political community that may serve as an equitable basis for accessing membership when no other lawful ground for membership acquisition is present.[32. Ayelet Shachar, The Birthright Lottery: Citizenship and Global Inequality (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2009), pp. 164–90. See also Shachar, “Earned Citizenship.” Related ideas refer to notions of a stakeholder society, or to the importance of social membership in determining access to citizenship. See Rainer Bauböck, “Expansive Citizenship—Voting beyond Territory and Membership,” Political Science & Politics 38, no. 4 (2005), pp. 683–87; and Joseph H. Carens, The Ethics of Immigration (New York: Oxford University Press, 2013).] This follows the basic moral intuition and legal practice holding that changes in relationships and expectations over time can necessitate shifts in legal status, an idea expressed in fields as diverse as contract law, family law, private international law, tax law, and property law, to name but a few. In the context of citizenship, nexi-based membership offers a concrete legal method to fulfill the idea of inclusive participation in a democratic society. This alternative captures a widely held sentiment that the Dreamers, who have been “raised as Americans,” deserve a legal path to regularize their status, just as it can serve as a method to delineate a minimal threshold of connection that EB-5 Parachuters must fulfill. On this account, a wire transfer cannot replace the actual experience of membership.

With mounting revelations of a global elite bent on tax offshoring and evading obligations to compatriots, citizenship ought to remain a realm of political relations grounded in real, everyday civic ties. Selling it to the highest bidder will eviscerate it from within.

Laws do not simply define categories and guide action; they also constitute that which they purport to describe.[33. On the expressive function of law, see Cass Sunstein, “On the Expressive Function of Law,” University of Pennsylvania Law Review 144 (1996), pp. 2021–253; on “performative” law, see J. L. Austin, How to Do Things with Words, 2nd ed. (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1975).] Likewise, markets do not just allocate goods; they also “express and promote certain attitudes toward the good being exchanged.”[34. Michael J. Sandel, What Money Can’t Buy: The Moral Limits of Markets (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2012), p. 9.] Government programs that authorize a market for purchasing and selling access to citizenship, transforming its acquisition into a bare-bones monetized transaction, are sending a clear message about who they value as potential future citizens. By giving priority to credit lines over civic ties, the global surge in programs such as the EB-5 may gradually, over the long haul, reshape the greater class of those who are likely to enjoy full membership, just as it provides a pretext for anti-emancipatory narratives of (economic) rationality for denying citizenship to those who cannot afford it from within.

While there is plenty of room for reinventing and reinvigorating citizenship at the local, regional, national, and supranational levels, opening it up to new members and new ideas for participation across borders, for-sale programs are not part of this inclusionary driven trend to reimagine the boundaries of the demos and the franchise. Instead, the golden visa route exacerbates inequity by vindicating the exclusivity of prized citizenship rewards. With mounting revelations of a global elite bent on tax offshoring and evading obligations to compatriots, citizenship ought to remain a realm of political relations grounded in real, everyday civic ties. Selling it to the highest bidder will eviscerate it from within. Allowing wealth to become a golden passport to citizenship will leave us with a world in which, as Oscar Wilde once put it, too many of us “know the price of everything and the value of nothing.”

A PDF version of this essay is available to subscribers. Click here for access.

NOTES

Abstract: In today’s age of restrictionism, a growing number of countries are closing their gates of admission to most categories of would-be immigrants with one important exception. Governments increasingly seek to lure and attract “high value” migrants, especially those with access to large sums of capital. These individuals are offered golden visa programs that lead to fast-tracked naturalization in exchange for a hefty investment, in some cases without inhabiting or even setting foot in the passport-issuing country to which they now officially belong. In the U.S. context, the contrast between the “Dreamers” and “Parachuters” helps to draw out this distinction between civic ties and credit lines as competing bases for membership acquisition. Drawing attention to these seldom-discussed citizenship-for-sale practices, this essay highlights their global surge and critically evaluates the legal, normative, and distributional quandaries they raise. I further argue that purchased membership goods cannot replicate or substitute the meaningful links to a political community that make citizenship valuable and worth upholding in the first place.

Keywords: citizenship by investment, immigration, marketization, commodification, United States, Canada, EB-5, DACA, genuine links, tiered membership

More in this issue

Spring 2018 (32.1) • Review

Environmental Success Stories: Solving Major Ecological Problems & Confronting Climate Change by Frank M. Dunnivant

Global environmental challenges such as climate change are sometimes viewed as so daunting and complex that we can only aim to mitigate rather than solve ...

Spring 2018 (32.1) • Review Essay

How Should We Combat Corruption? Lessons from Theory and Practice

In this review essay, Gillian Brock surveys four recent books on corruption, all of which offer important insights.

Spring 2018 (32.1) • Essay

Beyond the BRICS: Power, Pluralism, and the Future of Global Order

Dramatic changes in the global system have led many to conclude that the focus on the BRICS reflected a particular moment in time that has ...