On December 10, 1948, the United Nations General Assembly passed the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), the most significant statement from the global community regarding what constitutes the ideal human life in any society and the rights to which all people are entitled. On the basis of the principles laid out in the UDHR, the international community has since negotiated a large number of human rights treaties and conventions and has developed plans of action in relation to all aspects of living a dignified life.

The UDHR is arguably one of the most important documents in the history of human civilization; and to the extent that words on paper can change the world, the impact of the UDHR has been profound. However, despite providing a solid foundation for our collective understanding of the rights to which human beings are endowed, today we are still far from realizing these goals, and threats to the very principles enshrined in the UDHR continue to emerge. The declaration has now endured for seventy years, roughly the global average human life span. Thus, this occasion presents a good opportunity to take stock of what has been achieved, what has yet to be accomplished, and to consider the future longevity of this seminal declaration.

As with any interpretation of something as complex as the impact of a document on the world, assessments of the UDHR and its ongoing role are mixed. Many in the field of human rights see a glass half full, characterizing the UDHR as a powerful tool that has dramatically shaped political and economic development throughout the world.1 Century (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 2017). Others focus on the space that remains empty, emphasizing the flaws that inhibit the realization of the document’s goals.2 Indeed, it must be admitted that, even given the indisputable progress that has been made over seven decades, there are today growing threats to human rights. These threats are the consequence of a number of global developments, including shifting geopolitical balances, extreme economic and social inequality, climate change, and a weakening of democratic institutions. These threats are very real, and it is important that human rights proponents monitor and respond to them. But here I argue that the threat to human rights is ever present. And thus, rather than focus on the advances and setbacks of this particular moment, this anniversary is an opportunity to consider the overall historical progression toward human rights as embodied in the UDHR and the obstacles that stand in the way of its full realization.

Taking this broader view, there are two issues in particular that stand out as barriers to be overcome. The first is tied to the Westphalian state system, which has come to dominate human political organization. State sovereignty presents a fundamental challenge to any effort to establish universal norms. Implementing universal human rights will always be tremendously difficult in a system that affords final authority to state leaders who lack the necessary incentives. This is nothing new or surprising, of course, and it is not unique to human rights. But it nonetheless requires a careful consideration of how international declarations make their way from ideas on paper to practice. A declaration is only significant to the extent to which it is adhered. As a document with universal endorsement, the UDHR does indeed have power, and it can shape the behavior of actors who otherwise risk appearing to stand against history and human civilization. It can also be used as a normative weapon, both by citizens and by the international community, to shame hypocrites who violate the principles to which they and every nation in the world have agreed. But it is, nonetheless, just a document, and without correspondingly strong global institutional mechanisms to ensure implementation and compliance, its impact is limited.

The second major issue is the way in which human rights ideals have been segmented. The separation of rights into social/economic and civil/political has enabled states to focus on some rights to the neglect of others. Global power shifts, especially under the hegemony of the post–Cold War United States, have led to exaggerated selective emphasis on just some of the rights embedded in the UDHR, when in fact none can be fully realized without a comprehensive approach. Political rights cannot be effectively exercised by those lacking access to basic economic necessities. And those meeting their economic needs may find that their voices as citizens are meaningless in a system characterized by vast inequality or in which national institutions are infected by mechanisms that leave them politically marginalized. Rights must be recognized as interconnected and they must be advanced in tandem. Emphasis on some principles to the exclusion of others undermines the comprehensive advancement of human rights. Thus, the current state of affairs is a product of the collective failure to address human rights holistically and to implement real monitoring and accountability measures for states, which are directly charged with upholding them within their borders.

Background

The concept of universal human rights obviously did not begin with the UDHR or even the founding of the United Nations. The core ideas behind some of these principles can be traced back to centuries prior.3 But following the devastation of World War II, world leaders were seeking to establish the conditions considered necessary to achieve global peace and stability, and respect for human rights was seen as a vital one of these conditions. While the UN Charter itself laid out the core principles, the UDHR was negotiated to establish firmly the rights that all member states would be expected to honor. Within its thirty articles, the declaration encompasses political, cultural, social, and economic rights. Political and civil rights include the rights to life and liberty, equality and equal protection before the law, freedom from torture, and freedom of speech and assembly. The cultural, economic, and social rights include the right to social security, employment, education, health, and participation in cultural life, including the right to rest and leisure time.

There are rich philosophical debates regarding the source from which human rights are thought to emerge and how precisely they are to be defined;4 but the modern architects of the UN human rights framework built into the UDHR the concept that these rights are inalienable and belong to the individual. As the Preamble clearly states, “the General Assembly proclaims the UDHR as a common standard of achievement for all peoples and all nations,” and UN Member States must strive to achieve the “recognition and observance” of these rights. So while the declaration frames these rights as inalienable, it is ultimately states that are responsible to ensure that they are codified into law and policy and duly fulfilled in practice.

The Role of the UDHR in Advancing Human Rights

The acknowledgement of the universality of human rights in itself does not guarantee that the ideals enshrined in the UDHR will be carried out in practice. While some scholars argue that we are currently seeing some slippage on human rights worldwide, the general historical trajectory of the past seventy years has nonetheless been positive. A careful consideration of social scientific data tells us that human rights have on the whole seen real improvement.5 While external factors such as demilitarization, development, and democratic governance have played a role in bettering conditions,6 without the ideals set forth under the UDHR and subsequent UN processes, it would be hard to imagine such improvements to human rights globally.

While declarations such as the UDHR lay the aspirational groundwork, the primary means by which human rights principles make their way into actual practice is through UN treaties. The UDHR has served to guide the development of all human rights conventions that followed, including those on racial discrimination, women’s rights, the rights of persons with disabilities, and the rights of children. In addition to these treaties, there have been several major international conferences that resulted in the creation of important plans of action, which serve as international guidelines for states to follow. These conferences have covered housing, women, reproductive rights and health, social development, and human rights in general.7

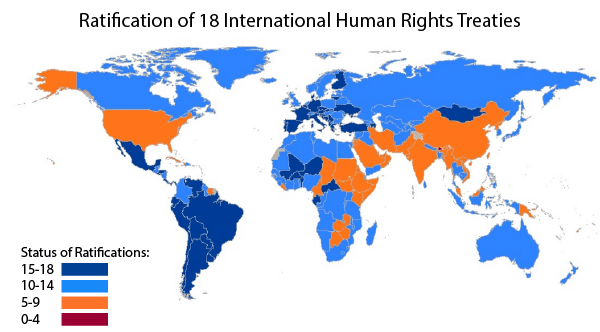

Map showing the number of international human rights treaties each country has ratified. (Photo Credit: UN OHCHR, modified)

Map showing the number of international human rights treaties each country has ratified. (Photo Credit: UN OHCHR, modified)

Social scientific analysis has demonstrated that treaties do indeed work.8 States that ratify treaties are more likely to include those rights as constitutional guarantees;9 and the constitutional recognition of international human rights treaties, along with judicial independence, subsequently leads to measurable improvement in human rights performance.10 The process starts with state commitment through treaty ratification, followed by a “cascading of the norms”11 as states pass laws and create the bureaucratic structures necessary to carry out associated policies. For example, women’s rights advanced worldwide in the wake of UN human rights activity on this topic. Global conferences on women’s rights were held starting in 1975, and led to the adoption of the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women in 1979. This in turn resulted in the passage of laws and the creation of bureaucracies worldwide focused on women’s rights.12 This example shows how treaties create normative pressure and provide citizens and domestic organizations with tangible standards around which to organize for changes in law and policy. Of course, this is especially so where local civil society organizations are able to demand compliance with treaty provisions.13 However, there is evidence that gains can be made through this process even when state leaders are not fully on board. Positive changes for the political and social rights of women were observed despite the fact that women’s human rights were the “most vigorously contested sovereignty referent” across the UN conferences in the 1990s.14

That women’s rights advanced despite this being a heavily contested topic in many parts of the world demonstrates the power of the UDHR: it creates a framework for real progress and shapes our understanding of human rights. Norms are continuously evolving, but the UDHR principles are sufficiently clear and encompassing that they have not only endured, they have served as the basis for a broadened understanding of how rights are to be applied and to whom. Groups historically not considered worthy of equal treatment can cite the fundamental principles enshrined in the UDHR as grounds for their inclusion and as a basis for asserting their rights. The declaration and its articles also serve as justification for calling conferences and negotiating conventions, which in turn serve as the basis for law and policy. These, when properly enacted and enforced, lead to the actual realization of fundamental rights and the betterment of life. In this sense, the UDHR has been of monumental importance to the advancement of human civilization. Thus, in assessing the document and its role in shaping present conditions, the glass may not be full, but it is undeniably more full than seventy years ago. Billions have drunk from it and had their thirst for dignity alleviated, if not fully quenched.

The Challenge of Advancing Human Rights on the Basis of the UDHR

What are the flaws in the document and the barriers to its implementation? The first and most basic problem, as noted earlier, is that in itself the UDHR includes no clear mechanism of implementation. All UN declarations, including the UDHR, are aspirational. They embody ideals and goals, but in themselves they provide no concrete framework for actually achieving them. The UDHR contains no means by which to monitor progress or provide support for the implementation of the aspirations laid out therein. The declaration may be universally endorsed, but the fact remains that people endowed with the rights enumerated in the UDHR live within states, and states remain sovereign. Human rights defenders can seek to institutionalize these principles through changes in law and policy, but it is states themselves that are the final arbiters. The voluntary basis upon which states actually implement and enforce human rights protection represents a fundamental weakness of any international declaration.

A weak monitoring and support mechanism is characteristic of virtually all agreements reached at the United Nations. Even when provisions for oversight are included, states still decide whether to carry out accountability measures. In that sense, the UDHR is no more powerful than any UN pronouncement. However, the UDHR is no ordinary resolution. It has served as the foundation for global understandings of human rights, and it has gone mostly unchallenged in that regard.15 And it is not simply a relic. It was formally and universally reaffirmed by 171 states at the Vienna Convention in 1993. Such a grand declaration gives power to the ideals it delineates; and this allows states, human rights organizations, and individuals to apply normative as well as legal pressure on violators. Consequently, even in the absence of institutional enforcement mechanisms, the UDHR has shaped state behavior.

In addition, over the years there have been steps to improve state accountability. The institutional framework through which states are assessed in regard to their progress toward universal human rights has been strengthened. Specifically, the treaties adopted based on UDHR principles include a review process as a way for states to take stock of their progress and to get feedback from peers and experts. Expert committees associated with each treaty carry out reviews and then make recommendations to state parties on how best to implement obligations under the treaty. There is also a process by which external actors, including intergovernmental organizations and nongovernmental organizations, file shadow reports with the expert committees during the treaty review. This process provides an independent assessment of progress made by state parties on human rights issues contained in the treaties. Collectively, these monitoring and reporting systems give guidance and put additional pressure on states and serve to strengthen the impact of the declaration.

The 34th Session of the Human Rights Council, Geneva. (Photo Credit: UN Photo / Elma Okic via Flickr)

The 34th Session of the Human Rights Council, Geneva. (Photo Credit: UN Photo / Elma Okic via Flickr)

Despite these improvements in accountability, however, action by states remains entirely selective and voluntary. While the UDHR has universal endorsement, ratification of its associated treaties is well short of universal. Moreover, only 33 of the 197 countries in the human rights treaty system are in full compliance with their treaty obligations; and at the time of this writing there are 585 reports overdue to the various treaty bodies.16 This leaves many states out of the realm of global scrutiny on core aspects of their human rights performance. That said, there have been some advances outside the context of formal treaties. For example, the UDHR Preamble alludes to the collective responsibility of the General Assembly to advance the declaration’s goals; and on that basis, as a part of the 2005 World Summit reaffirming state commitments to the United Nations during the organization’s sixtieth anniversary,17 members agreed to the creation of the Human Rights Council. The Council, which is composed of forty-seven states elected by the General Assembly, is charged with conducting what are called Universal Periodic Reviews, through which it scrutinizes and reports on every state’s human rights performance.

Despite improvements in accountability mechanisms, cynics may dismiss it all as words on paper. And the reality of selective state participation may justify some of this cynicism. There is no linear path from the ideal to the real when it comes to human rights. There is no clear pass-implement-enforce process for the international community as there typically is in a domestic context. But endorsing an agreement together with every other state in the world does create expectations. Filing reports or accepting external monitors does have a way of shaping behavior. And at the root of virtually every step toward the advancement of human rights, however small or indirect, lies the UDHR.

The Split in the Human Rights Framework

In addition to the absence of any strong accountability mechanism, a second significant shortcoming can be seen in the way that human rights principles are almost always cited selectively. This again cannot be considered a flaw in the UDHR itself, but in the broader structures through which such declarations are supposed to make their way into practice. The rights delineated in the UDHR are commonly bifurcated between civil and political rights (freedom of speech, of assembly, of religion) on one side and economic (social security, the right to work, adequate standard of living) and social rights (access to education, healthcare) on the other. States tend to emphasize the areas of human rights where they are strong in order to pressure others who fail to match these achievements, even while they themselves fall far short in other areas. This dynamic was obvious during the Cold War when the United States and Western powers would hammer the Eastern bloc for its shortcomings on political and civil rights. The Soviet Union and its allies would in turn highlight the poverty, inequality, and lack of economic rights in the capitalist world. This opportunistic segmenting of rights led to uneven global progress. With the spread of neoliberalism in the post–Cold War era, economic rights have fallen by the wayside in more areas of the world. This is problematic not just on economic merits but also because without corresponding economic rights gains in other areas are imperiled.

Unchallenged economic power leaves large groups of people severely disadvantaged and places their other rights at risk. As income inequality increases, so does violence in the form of arbitrary detention, torture, political imprisonment, and disappearances.18 There is a direct link between poverty and social exclusion more generally. In order to avoid an overall decline in rights, governments must simultaneously develop politically and economically inclusive policies and institutions.19 As it now stands, in much of the world economic rights have not been accorded sufficient attention.

It is not surprising that under the hegemony of the United States, socioeconomic rights have been deemphasized. The ambivalence of the United States toward these rights has been well documented,20 and this sentiment has shaped the terms of the global debate around economic rights. Critics such as Amartya Sen argue that development needs to be approached as a means to provide people with freedoms; that the notion of economic rights is still fundamental.21 But talk of economic “rights” has been largely displaced by an emphasis on economic development and growth. Over time, this has created a silo effect between what has come to be called the development agenda and the human rights agenda.22 The assumption is that economic wellbeing will be addressed as a matter of course if economic growth can be achieved. If true, there is little value in considering rights-based economic measures. Nearly all states have embraced the liberal development model,23 and it has even made its way into UN programs, such as the UN Development Programme (UNDP), UNICEF, and World Food Programme.

Starting as early as the 1960s, but fully coming into force in the 1980s, state economic policies have been growth based. Recognizing that this type of development model would not produce desired levels of improvements for economic human rights, a limited rights-based outlook has slowly been incorporated into some UN programs since the late 1990s. In 1998, for example, UNDP issued its “policy of integrating human rights with human development.”24

The Millennium Development Goals. (Photo Credit: Wikimedia Commons)

The Millennium Development Goals. (Photo Credit: Wikimedia Commons)

But even then the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), the most ambitious development plan adopted by the General Assembly at that time, did not use a human rights framework. The MDGs, a set of fifteen-year goals adopted in 2000, marked the first time that states set concrete benchmarks to address poverty, gender inequality, education, health, and sustainability. Though they incorporated social rights and gender equality, the MDGs did not address the structural issues that lead to lack of development. And they offered no certain remedy, as they were about “development” as interpreted from a results-based perspective, rather than a rights-based point of view.

That said, there are today continuing signs of progress toward a more comprehensive and encompassing approach to human rights. A development agenda that identifies “development as freedoms” as opposed to economic growth25 is being slowly incorporated into UN programs and funds. While this type of cosmopolitan outlook has been in discussion in policy circles for some time, its incorporation into the global policy framework has been quiet, slow, and marginal, still running into a strong barrier in neoliberal economic ideals with an emphasis on growth over rights. The “development as freedom” approach recognizes the purpose of development as being to enable people to exercise economic rights. The greater emphasis on rights is an important step toward overcoming a development approach that sees growth as the end in itself, while ignoring the threat posed by extreme inequality and the fact that many are left out, even in prosperous societies.

The MDGs expired in 2015 and were replaced with a new set of fifteen-year objectives, the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The SDGs represent an improvement in that they utilize more of a rights-based framework when addressing economic and social issues. For example, they ask that states implement the International Labour Organization’s work-related treaties—structural measures that guarantee workplace rights. The SDGs are a further improvement over the MDGs in that they begin to include civil and political rights within a development context. While a full incorporation of a socially just and politically representative economic system has not been at the center of these development goals, Goal 16, regarding “peace, justice, and strong institutions,” has started a conversation about political and civil rights on the margins of development discussions. The mention of “peace, justice, and strong institutions” within the SDGs was itself the product of compromise, and came as a concession from those states that wanted to leave those issues off the agenda. These are small steps, true, but they indicate a growing recognition that rights must be addressed in a holistic manner, and that economic rights must be guaranteed in the same way as political and civil rights.

The Sustainable Development Goals. (Photo Credit: Wikimedia Commons)

The Sustainable Development Goals. (Photo Credit: Wikimedia Commons)

The inclusion of the private sector, historically left out of the human rights discussion, is another means by which the United Nations is seeking to bring more attention to economic rights. The private sector is an important stakeholder; and in the context of a neoliberal world order, the power of some private sector actors dwarfs that of many states. UN-based programs such as the Global Compact, which encourage a shift in corporate norms and provide standards of good behavior, are additional means of addressing human rights in the economic realm. But seeking compliance with voluntary standards is subject to the same challenges as those encountered with state actors. Asking firms to modify behavior to meet certain goals is very different from guaranteeing fundamental rights to workers or consumers, and it also runs the risk of reinforcing the mistaken notion that economic rights can be parceled into a separate, optional category. Voluntary private sector involvement in the economic aspects of human life has shown promise in some respects, but it can also be viewed as a step away from the notion that rights need to be thought of in a holistic manner and that their achievement should be universally assured.

Conclusion

It is easy to be cynical about declarations that come out of the byzantine UN bureaucracy. Symbolic statements are issued regularly and the international community has no effective means of enforcement or accountability. But not all such statements are created equal. Any declaration endorsed by every country in the world is important, and one that defines universal rights is perhaps the most significant statement that can be made. While one can point to texts that are important to certain groups during certain historical periods and that have had profound effects on human civilization, few can be considered universal in their reach. It is true that there is no definitive mechanism through which the goals of the UDHR can be enacted. This is the challenge for any world comprised of sovereign states. Nevertheless, the UDHR has served as an essential tool to advance the rights of people everywhere. The path forward may be slow and winding, and there may be stalling along the way, but one need only look back to see that there is indeed a path being forged.

How we move forward is not always clear, but it is evident that rights must advance together. We cannot favor some to the exclusion of others. We would not want a world in which everyone is materially comfortable and cared for, but lacking in rights of free speech or self-determination. Similarly, we do not want a world in which people have the nominal rights to vote or assemble, but lack the basic economic necessities to be able to exercise them. The UDHR was written to include all the fundamental rights to which humans are endowed. Upholding some and ignoring others undermines the entire project.

A PDF of this essay is available to subscribers. Click here for access.

---

- 1 Todd Landman, Protecting Human Rights: A Comparative Study (Washington, D.C.: Georgetown University Press, 2005); Todd Landman, “Social Magic and the Temple of Human Rights: Critical Reflections on Stephen Hopgood’s Endtimes of Human Rights,” in Doutje Lettinga and Lars van Troost, eds., Debating the Endtimes of Human Rights: Activism and Institutions in a Neo-Westphalian World, The Strategic Studies Project, Amnesty International Netherlands (2014); and Kathryn Sikkink, Evidence for Hope: Making Human Rights Work in the 21st ↩

- 2 Stephen Hopgood, The Endtimes of Human Rights (Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 2013); and Samuel Moyn, Not Enough: Human Rights in an Unequal World (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2018). ↩

- 3 Paul Gordon Lauren, “History of Human Rights,” and Michael Freeman, “Philosophy,” in David P. Forsythe, ed., Encyclopedia of Human Rights (New York: Oxford University Press, 2009). ↩

- 4 See Christopher N. J. Roberts, The Contentious History of the International Bill of Rights (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2015). ↩

- 5 Ann Marie Clark and Kathryn Sikkink, “Information Effects and Human Rights Data: Is the Good News about Increased Human Rights Information Bad News for Human Rights Measures?” Human Rights Quarterly 35, no. 3 (2013), pp. 539–68. ↩

- 6 Sonia Cardenas, “Human Rights in Comparative Politics,” in Michael Goodhart, ed., Human Rights Politics and Practice (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013), p. 83. ↩

- 7 See Elisabeth Jay Friedman, Kathryn Hochstetler, and Ann Marie Clark, Sovereignty, Democracy, and Global Civil Society: State-Society Relations at UN World Conferences (Albany, N.Y.: SUNY Press, 2005). ↩

- 8 While Oona Hathaway has argued that human rights treaties do not have a positive impact on human rights performance in states that ratify them, a nuanced analysis of treaty ratification shows that domestic political conditions, especially the strength of civil society, matter in the effectiveness of human rights treaty implementation. Oona A. Hathaway, “Do Human Rights Treaties make a Difference?” Yale Law Journal 111, no. 8 (2002), pp. 1935–2042; Emilie M. Hafner-Burton and Kiyoteru Tsutsui, “Human Rights in a Globalizing World: The Paradox of Empty Promises,” American Journal of Sociology 110, no. 5 (2005), pp. 1373–411; and Eric Neumayer, “Do International Human Rights Treaties Improve Respect for Human Rights?” Journal of Conflict Resolution 49, no. 6 (2005), pp. 925–53. ↩

- 9 Jody Heymann, Kristen McNeill, and Amy Raub, “Rights Monitoring and Assessment Using Quantitative Indicators of Law and Policy: International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights,” Human Rights Quarterly 37, no. 4 (2015), pp. 1071–100. ↩

- 10 Neil A. Englehart and Melissa K. Miller, “The CEDAW Effect: International Law’s Impact on Women’s Rights,” Journal of Human Rights 13, no. 1 (2014), pp. 22–47; and Wayne Sandholtz, “Treaties, Constitutions, Courts, and Human Rights,” Journal of Human Rights 11, no. 1 (2012), pp.17–32. ↩

- 11 Jacqui True and Michael Mintrom, “Transnational Networks and Policy Diffusion: The Case of Gender Mainstreaming,” International Studies Quarterly 45, no. 1 (2001), pp. 27–57. ↩

- 12 Heymann et al., “Rights Monitoring and Assessment”; and True and Mintrom, “Transnational Networks and Policy Diffusion.” ↩

- 13 Olga Avdeyeva, “When Do States Comply with International Treaties? Policies on Violence against Women in Post-Communist Countries,” International Studies Quarterly 51, no. 4 (2007), pp. 877–900; and True and Mintrom, “Transnational Networks and Policy Diffusion.” ↩

- 14 Friedman et al., Sovereignty, Democracy, and Global Civil Society, p. 165. ↩

- 15 There have been critiques questioning the universality of human rights, for example based on colonial attitudes, see Makau W. Mutua, “Savages, Victims and Saviors: The Metaphor of Human Rights,” Harvard International Law Journal 42, no. 1 (2001), pp. 201–45; or, for example, whether they can be reconciled in relation to democratic principles, see Michael Ignatieff, “Reimagining a Global Ethic,” Ethics & International Affairs 26, no.1 (2012), pp. 7–19. Yet, these critiques are not of the rights themselves but of the process by which these rights can be ethically implemented given the global power and institutional structures. ↩

- 16 Ibrahim Salama, Strengthening the UN Human Rights Treaty Body System: Prospects of a Work in Progress (Geneva: Geneva Academy, 2016); and website of the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, tbinternet.ohchr.org/_layouts/TreatyBodyExternal/LateReporting.aspx (accessed June 19, 2018). ↩

- 17 See General Assembly Resolution 60/1, “2005 World Summit Outcome,” A/RES/60/1, adopted September 16, 2005. This document was developed through high-level meetings between member states of the United Nations and it reaffirms state commitment to the UN general principles including human rights and reflects on how to improve all facets of the working of the United Nations on its sixtieth anniversary. ↩

- 18 Denise González Núñez, “Peasants’ Right to Land: Addressing the Existing Implementation and Normative Gaps in International Human Rights Law,” Human Rights Law Review 14, no. 4 (2014), pp. 589–609. ↩

- 19 Todd Landman and Marco Larizza, “Inequality and Human Rights: Who Controls What, When, and How,” International Studies Quarterly 53, no. 3 (2009), pp. 715–36. ↩

- 20 See Roberts, The Contentious History of the International Bill of Rights, ch. 4. ↩

- 21 Amartya Sen, Development as Freedom (New York: Random House, 2000). ↩

- 22 Gauthier de Beco, “Protecting the Invisible: An Intersectional Approach to International Human Rights Law,” Human Rights Law Review 17, no. 4 (2017), pp. 633–63. ↩

- 23 David Harvey, A Brief History of Neoliberalism (New York: Oxford University Press, 2005). ↩

- 24 UNDP, Democratic Governance Reader: A Reference for UNDP Practitioners (2009), p. 6, www.undp.org/content/dam/aplaws/publication/en/publications/democratic-governance/oslo-governance-center/democratic-governance-reader/DG_reader-2009.pdf (accessed May 29, 2018). ↩

- 25 Sen, Development as Freedom. ↩

More in this issue

Winter 2018 (32.4) • Review

Briefly Noted: Grave New World: The End of Globalization, the Return of History, by Stephen D. King

A brief book review of Stephen D. King's Grave New World.

Winter 2018 (32.4) • Review

A Foreign Policy for the Left, by Michael Walzer

Michael Walzer’s new book brings together essays from the past sixteen years to offer pragmatic ethical guidance on matters of foreign policy.

Winter 2018 (32.4) • Feature

Reforming the Security Council through a Code of Conduct: A Sisyphean Task?

In this feature, Bolarinwa Adediran disputes the utility of a code of conduct to regulate the exercise of the veto at the UN Security Council ...