Governing the World: The History of an Idea, Mark Mazower (New York, Penguin Books, 2013), 496 pp., $29.95 cloth, $18 paper.

Divided Nations: Why Global Governance Is Failing and What We Can Do About It, Ian Goldin (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), 200 pp., $21.95 cloth, $15 paper.

The Great Convergence: Asia, the West, and the Logic of One World, Kishore Mahbubani (New York: Public Affairs, 2013), 328 pp., $26.99 cloth, $16.99 paper.

As of 2007 the world economy has been caught in the worst crisis since the 1930s. Yet after two years of only partly successful efforts to mobilize and coordinate global action of financial control and stimulus, ending with the G-20 meeting of March 2009, responsibility for corrective economic initiatives has essentially been left to individual countries, supported by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the European Union (EU). Moreover, such support has been usually conditional on countries following financial policies of tough austerity. The United States took some actions to stimulate its economy, but by many accounts these were insufficient. Most of Europe has not even attempted stimulus measures and has been in a period of economic stagnation, with falling real incomes among the poorest parts of the population. Although some signs of “recovery” have been heralded in 2013 and 2014, growth has mostly been measured from a lower base. There is little evidence of broad-based economic recovery, let alone improvements in the situation of the poor or even of the middle-income groups.

Three books take on these failures of global governance, all looking well beyond the short run to the longer-term priorities of the twenty-first century. In Governing the World: A History of an Idea, Mark Mazower reviews the changing global preoccupations and efforts of institutional creation, some successful, some not, over the last 200 years, beginning with the Concert of Europe in 1815. In Divided Nations: Why Global Governance Is Failing and What We Can Do about It, Ian Goldin focuses on the weaknesses of the United Nations, World Bank, and other global institutions, especially in relation to present-day challenges of tackling the urgent needs for global public goods. Both books are highly pessimistic. For Goldin, “the absence of global leadership and even awareness of the scale of the global challenges” should keep us awake at night (p. XII). Mazower’s verdict is no less severe. For him, “the idea of governing the world is becoming yesterday’s dream” (p. 427). In sharp contrast, The Great Convergence: Asia, the West, and the Logic of One World, by Kishore Mahbubani, brims with Asian optimism. Mahbubani, a former UN ambassador, recounts some of the successes in global governance of recent decades and then presents his recommendations about the way forward.

THE EARLY EXPERIENCES OF INTERNATIONAL GOVERNANCE

Mazower’s book is highly substantive, tracing two centuries of history with magisterial overview and a wealth of detail and fascinating asides. He shows that clear political ambition backed up by the controlling influence of the great powers lay behind what he calls “the very first model of international government” (p. XIV). After the defeat of Napoleon, statesmen of Austria, Russia, Britain, and Prussia created a conclave known as the Concert of Europe. These were the great powers of the day, with France accepted soon afterwards. The conclave met regularly from 1815 onward to “prevent any single power from ever again dominating and to stamp out revolutionary agitation before it could lead to war” (p. XIV). The links and tensions between international perspectives/objectives and changing national ones remain a continuing feature of international organization.

Once the idea of concerted international action was set loose, it was picked up enthusiastically by a wide variety of other international groups, and many different perceptions were stimulated. As Mazower notes:

Karl Marx dreamed of workers banding together; Mazzini . . . hoped republican patriots would forge a world of nations. Protestant evangelicals mobilized to hasten the brotherhood of man. Merchants and journalists called for free trade and the spread of industry. Scientists dreamed of new universal languages . . . spreading technical knowledge and carrying out great engineering projects that would unite humanity. . . . Lawyers . . . urged states to give up war and to allow their differences to be settled by arbitration or through a world court (pp. XIV–XV).

One of the more interesting sections of Mazower’s account examines the role of thinkers and intellectuals, even before the nineteenth century, in envisioning global institutions. Immanuel Kant produced his classic essay on perpetual peace; Novalis, a young German mystic, called for a return to earlier times of “one peaceloving society” when “one common interest joined the most distant provinces of this vast spiritual empire”; Jeremy Bentham invented the term “international” in order to contrast it with the law of nations, which he found sloppy.

Peace was a common theme and objective of global governance over many years. In the first half of the nineteenth century, Mazower notes, “there were no more ardent internationalists to be found anywhere than among evangelical Christians.” A Society for the Promotion of Permanent and Universal Peace, founded in 1816 by British dissenters and evangelicals, was “principled against war upon any pretence,” and linked with the promotion of missionary activities and the civilizing mission. These peace movements continued until the midcentury, when they began to lose momentum due to rising tensions in the Crimea (which stirred up anti-Russian belligerence in Britain and effectively put an end to the peace movement there) and in the United States (where peace activists took up the side of the North in the Civil War). The spirit of internationalism survived, but in a more chastised and less Christian form. It pursued the peace ideal in more indirect ways and focused more on institutions. Moreover, by midcentury it had a successful model to look up to: international commerce and the rise of the free trade movement, which provided an alternative and more materialist rationale for internationalism.

An interesting point is that both the Christian and the free trade movements looked to public opinion to carry forward their vision, rather than to any government-supported international organization. To some extent, lawyers thought otherwise. There was a strong legal movement to see international law codified and implemented as the route to peace, at least among “civilized nations.” But when some of the “uncivilized” parts of the world displayed their military prowess, as the Japanese did over the Russians in 1905, the idea of a hierarchy based on civilization with Europe at the top came to an end. A legal approach to global governance began then to be seen as problematic, and arbitration based on power and interests resumed a dominant place.

The rapid advance of technological developments during the nineteenth century, on the other hand, led to many international agreements and new organizations. The obvious needs for efficiency and a technical approach to coordination led to the creation of the International Telecommunications Union in 1865 and the Universal Postal Union in 1874. Various efforts to ensure uniformity in weights and measures culminated in an international conference promoting the metric system in 1875. But the dream of an overarching framework for global governance remained elusive.

THE LEAGUE OF NATIONS

“Yet,” Mazower summarizes, “the limits of nineteenth century internationalism are as striking as the ambition. Internationalism suited small states like Belgium and Switzerland, in particular, and they were among its principal sponsors. But the buy-in of the major powers was still very limited” (p. 117). What, then, was the big change that led to the setting up of the League of Nations in 1919? “Why,” Mazower asks, “did Britain, and even more strikingly, the United States, emerge from the First World War convinced, not as many believed, that internationalism had failed, but that it must be given new prominence and weight?” (p. 117). Of course, central to the story is the well-known role played by Woodrow Wilson. Inspired by his religious upbringing, Wilson thought “in biblical terms of covenants, not contracts. . . . He sought to build something which would grow organically over time to meet mankind’s universal aspirations, not the interests of a few powers who could probably get along anyway” (p. 121). In this, Wilson was turning to institutions and away from the idea of arbitration, which had been central to his two Republican predecessors, Roosevelt and Taft, as well as Roosevelt’s secretary of state, Elihu Root.

First meeting of the League assembly in 1920. Via Wikimedia.

First meeting of the League assembly in 1920. Via Wikimedia.

The British, too, were beginning to think in terms of institutions. Lloyd George, with a mixture of imperial bravado and national self-satisfaction, declared shortly before the Versailles conference that “the British empire is a league of nations.” This declaration, according to Mazower, helps explain why the British, traditionally skeptical of international commitments, were positive toward the new proposals: the idea of a postwar organization that would preserve the peace and the Anglo-American alliance was inextricably linked to the goal of the preservation of empire. The role of certain individuals, notably Robert Cecil, undersecretary of foreign affairs in Britain and the foremost British exponent of the League, was also critical. There was also Jan Smuts, the South African prime minister and politician, who saw the British Commonwealth of Nations as a step toward “future World Government . . . which could guide future civilization for ages to come.” Mazower credits Cecil as much as Wilson for the fact that the League of Nations came to birth.

According to Mazower, it was at the Conference of Versailles in 1919 where the personal diplomacy of the Cecil-Smuts team “basically ignored the instructions they had been given by the [British] cabinet, and used the support of Woodrow Wilson to trump the objections of their own prime minister” (p. 135). Thus began the arrangement under which the United States provided the money and Britain the brains behind the new organization. But the League’s almost total abandonment of the legalist paradigm and Wilson’s disdain for the Republican-dominated U.S. Senate led to that body’s rejection of the treaty setting up the League. Thus, in January 1920, when more than forty member countries met in Paris for the first council meeting of the League, the U.S. chair at the main table was empty.

It is well known that, politically and economically, the League largely failed. Yet Mazower shows the important and substantial successes achieved by the League in the social arena—in health, nutrition, and statistics—often with financing from Carnegie, Rockefeller, and other U.S. philanthropists. The League also demonstrated the feasibility and importance of establishing the elements of an international secretariat that was impartial, efficient, and lean, and that at the same time could exercise quiet leadership. At its largest, the League’s secretariat employed only 650 people and had a budget that (in real terms) was one-thirtieth of the United Nation’s budget today, yet it achieved a great deal, and several of its leading civil servants went on to play crucial international roles in creating the United Nations after the Second World War. From this perspective, Mazower concludes, “it is not the League’s failures that we should focus on, but its enduring influence” (p. 153). In particular, he notes, the League was a “vehicle for world leadership based on moral principles and the formal equality of sovereign states, it preached the beginning of a new internationalist dispensation, repudiated the legacy of the Holy Alliance and the Concert of Europe, and offered the promise of democratization and social transformation through technical expertise. In fact, the League was the first body to marry the idea of a society of nations with the reality of Great Power hegemony” (p. 153).

THE UNITED NATIONS

Mazower devotes the second half of his book to the era of the United Nations, which he entitles “Governing the World the American Way.” His analysis of this well-trodden field is impressive, especially because he brings in many original elements, drawing on a range of recent detailed studies, including many doctoral theses. The United Nations has been pushed and pulled by massive changes since its founding in 1945. But though politically buffeted, financially constrained, and increasingly sidelined, it has never totally lost its position of legitimacy and global leadership. Indeed, there have been periods of resurgence in U.S. support for the international organization, and almost always steady support from the Group of 77. In the late 1940s there was even a brief period when many in the United States became interested in the ideas of World Federalism. Congress held hearings on the topic, and 56 percent of those questioned in a Gallup poll supported the view that “the UN should be strengthened to make it a world government.” But this was an exception to long-standing U.S. attitudes of ambivalence toward the organization.

As frequently emphasized, decolonization changed the balance of voting power at the United Nations in the 1960s. This had two main long-term consequences: first, the principle of national self-determination became the basis for the new internationalism; and, second, the award of full citizenship rights to many very small island states opened the door to disintegrative rather than integrative global forces —exactly the opposite to what Mazzini, Mill, and Marx had hoped for. Thus, Mazower summarizes, “Politics at the UN became ever more about symbols and ever less about substance.” And, he adds in what is surely one of several overstatements, “decolonization marked not only the UN’s triumph but its world-historical culmination” (p. 272).

On development, Mazower covers a large territory, skillfully touching on most of the main issues in barely thirty pages, largely by focusing on U.S. interests and how the United States’ ambidextrous approach enabled Washington to work either multilaterally or nationally, depending on what the circumstances dictated. Over the years the United Nations has provided political cover for U.S. interests at absurdly little cost. American money paid for a proliferation of an international cadre of political technical experts at relatively little cost, which enabled American knowledge to ramify around the world, “with huge implications for the way development was conceived.” At the same time, Mazower comments, “As development turned into American social science, it became a more top-down affair, with fewer real conversations with people from the countries concerned” (p. 285). This is an interesting comment, but surely one which many would debate. My own view is that Mazower’s strictures apply more to the Bretton Woods Institutions than to the United Nations, which, in matters of development, has been more multidisciplinary, less dogmatic, and more sensitive to the views and positions of developing countries.

Take, for instance, the rise of the IMF and the World Bank from the 1970s to the 1990s. The IMF moved from being a funder to being a global engineer, masterminding significant domestic policy changes, and using conditionality to ensure compliance from countries doubting the reasonableness of the policies being imposed. Mazower is sharply critical of both the IMF and World Bank, pointing the finger at staffers in both institutions for a succession of costly errors of economic policy:

Most of the economists in the IMF had little interest in history, nor in the other social sciences. Their staffers were mostly male, and almost entirely economists trained in American and English universities. Entering the IMF and the World Bank in the 1980s, they were rational-expectation revolutionaries, who based their prescriptions on in-house templates couched in the language of the highly formalized mathematical models that the profession was coming to prize. Practioners of perhaps the most successful single discipline in the postwar American university, they existed in a state of more or less total ignorance of the cultures, languages, or institutions of the countries they had been told to cure, having been trained, as many economists still are, to believe that this ignorance—being a matter of “exogenous variables”—did not matter (pp. 353–354).

The results of these errors were often devastating. The UN Development Programme documented how in 1996 some 70 countries were poorer than they were in 1980, and 43 were poorer than in 1970.[1. United Nations Development Programme, Human Development Report 1996 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1996), pp. 1–3.] Mazower also emphasizes how adjustment policies led to an extraordinary transformation of property relations throughout the world, with water, electricity, coal, trains, buses, and other nationalized industries sold off to private corporations. In parallel to these national actions, world trade was being subject to free market principles, at least in the sense that developing countries were being required to open up their markets—without a reciprocal requirement for developed countries.

Thus, while contrasting the twentieth century with the nineteenth, Mazower emphasizes that even though global institutions became more ordered over time, it was once again the great powers that took the initiative and disproportionately reaped the benefits. As Mazower explains the process: “Large international organizations such as the League of Nations and the UN did not grow up gradually. On the contrary, sponsored by Great Powers, their births were abrupt, and war was their midwife. . . . Hardwired into the new international bodies from the start was an inevitable tension between the narrower national interests that the Great Powers sought to promote through them and the universal ideals and the rhetoric that emanated from them” (p. XV).

OSSIFIED INSTITUTIONS

Although the world is more connected than ever before, ossified global institutions are losing the battle for better global governance. This is the key claim of Ian Goldin in Divided Nations: Why Global Governance Is Failing and What Can Be Done about It. Goldin draws on his experience in an impressive string of senior positions in a variety of countries and international institutions as well as on his and his colleagues’ research in the Oxford Martin School at the University of Oxford.

The core of Goldin’s analysis concerns the need for global public goods and the inadequacy of their current provision in five key areas: climate change, cybersecurity, pandemics, migration, and finance. In each of these, claims Goldin, there are both serious emerging risks, largely due to globalization, and a growing gap between “yesterday’s structures and today’s problems.” The book presents an impressive analysis, displaying a down-to-earth realism backed up with good statistics and some interesting but little-known facts. Goldin stresses how stronger global action requires both greater transparency and greater coordination of information as well as more effective incentives and actions to deal with growing risks and free-riding. A country may agree to collective action but then fail to comply in the hope that it will gain the benefits of other countries fulfilling their part of the bargain. Failure to curb emissions is one clear example of this phenomenon, while failure to pay financial dues for agreed collective action is another.

Goldin suggests five principles to guide future action, devised with Ngaire Woods, a colleague at Oxford University. First, focus on the countries that have sufficient interest to support what needs to be done. Not all issues require global collective action, at least to get started. This can be a highly positive approach to the whole process of negotiation. Second, adopt the principle of selective inclusion. This follows from the first: why go for universality if not every country has significant involvement in the issue? Third, adopt the principle of variable geometry, by which the author means a process that takes account of the interests and situations of different groupings of countries in order to achieve compliance and efficiency. Fourth, ensure that global management has legitimacy. Fifth, and finally, institute some degree of enforceability.

These have the ring of practical politics, but one is left wondering how well these principles really cover the big questions of global governance. They may fit well the specifics of high-cost and highly technical concerns, but surely do not apply to all issues, such as pandemics or climate change or even cybersecurity, where poorer and weaker countries may not be big players but must reckon with the consequences of inadequate, unrepresentative global governance. And in the world of cybersecurity, the weakest link of the chain may be the one that breaks. This said, one is left wondering whether a global governance perspective largely focused on public goods is broad enough. The well-rehearsed issues of free-riders explain a good deal of the failure of governments to take action in areas where they have much to gain from collective action. For climate change, Goldin quotes Lord Stern’s estimate that the benefits of action would be ten times the costs—an example of the gross economic inefficiency that characterizes present global governance. Moreover, even such summaries overlook the inequalities of the impacts of climate change on the poorer parts of the world, along with the broader risks in terms of human life, civil unrest, and even war. For example, in Global Governance and the UN: An Unfinished Journey (2010) Tom Weiss and Ramesh Thakur have identified the need to take account of many other critical issues in global governance: peace, arms control and disarmament, collective security, technical coordination, terrorism, trade and aid, human rights, and the responsibility to protect.[2. Thomas G. Weiss and Ramesh Thakur, Global Governance and the UN: An Unfinished Journey (Bloomington, Ind.: Indiana University Press, 2010).]

ASIAN OPTIMISM

Infused with Asian optimism, Kishore Mahbubani’s The Great Convergence presents a view of the future in which Western dominance is long past but where Western traditions and leadership are still valued. The book pursues what Mahbubani terms “the logic of one world”—a rational analysis built on the need for new strengths in global governance and a revival of the United Nations. Mahbubani is a well-informed observer, with two stints as Singapore’s Ambassador to the United Nations and three appearances in Time magazine’s list of “100 global thinkers.” He is currently Dean of the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy.

Mahbubani’s analysis, less polemical than some of his earlier writings, is built on three main pillars. First is Asia’s growing place in the world, which is premised not only on economic growth but several related factors: notably its growing middle class, which is projected to double by 2020 and to account for 40 percent of global middle-class consumption. Mahbubani also notes the continent’s increasing dominance in higher education. China, for instance, awarded more than a half-million doctorates in 2009, up from 12,000 in 2001. In 2010 it graduated 500,000 engineers, and awarded 10,000 engineering PhDs. In contrast, the United States graduated only 8,000 PhD engineers, an estimated two-thirds of whom were not U.S. citizens!

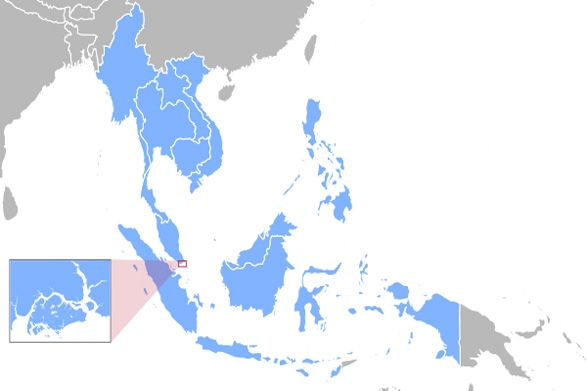

Second is Southeast Asia’s political and economic experience as an example for the global community. Mahbubani points out that no other region is as diverse in religious, ethnic, cultural, and political terms. It comprises almost 600 million people: 300 million Muslims, 230 million Buddhists, 80 million Christians, and 5 million Hindus—all encompassing several denominations. There is even greater ethnic diversity; and on the political front, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) includes the full spectrum of political systems. Yet none of these differences have held back rapid progress and collaboration on a wide range of economic and political initiatives. Mahbubani draws thought-provoking contrasts with the EU, which he describes as a “club of Christian majority states with only one kind of political system” (p. 39).

ASEAN member states. Via Wikimedia.

ASEAN member states. Via Wikimedia.

Third is the “deep fissure” that the author believes exists between the dominant Western narrative about the United Nations and that of the rest of the world. In his view, most Western, and especially American, citizens believe the United Nations to be “a vast, bloated, inefficient bureaucracy that does little good,” while the vast majority of those outside the West “retain massive trust” in the organization (p. 91). He posits that “if the West understood global trends, it would immediately begin to take advantage of this trust to secure its long-term interests,” saying that this would be a “master stroke” of geopolitics (p. 91).

Mahbubani’s grounds for optimism lie in Southeast Asia’s remarkable postwar turnaround. For decades after World War II it was one of the most troubled spots in the world, with massive losses of lives through regional wars—more than in the entire Middle East during this period. When China attacked Vietnam following the latter country’s invasion of Cambodia, each side fielded a million soldiers. The Cambodian genocide alone cost 2.4 million lives.

So how did Southeast Asia transform itself into the most stable and promising developing region in the world? Mahbubani points to four main ASEAN achievements. The first is preventing conflict between its members. While ASEAN, unlike the EU, has not yet achieved “zero prospect” of war, it is clearly moving in that direction. Second, it has promoted cooperation in economic and other areas. Third, the region has engaged consistently with global powers, having recognized the futility of trying to keep them out. And fourth, it has deepened relationships by moving beyond government cooperation toward people-to-people exchanges, for example through university scholarships and interactions over technological platforms.

According to Mahbubani, “ASEAN provides a powerful microcosm of the great convergence that the world is experiencing” (p. 193). In The Great Convergence, he discusses how the ASEAN example could be followed at the global level through five norms: acceptance of modern science, logical reasoning, free-market economics, a transformation of the social contract, and multilateralism. All are needed, he suggests, to tackle the twenty-five global challenges he identifies, which range from climate change to genetic engineering. He attributes the present failure to deal with these issues to “global irrationality.” Certainly, weak analysis of the global economy, including by academics and the media, is part of the problem. But it might be clearer if Mahbubani described “global irrationality” more directly as the failures of political leadership and shortsighted policymaking on the national, regional, and global level—including in the ASEAN countries.

This brings Mahbubani to the United Nations. He points to the UN regular budget, which amounts to just $2.6 billion a year—a tiny fraction (roughly 0.004 percent) of the world gross national product and less than 4 percent of what the world spends each year on nuclear weapons. Nonetheless, governments slashed the UN budget by 5 percent in December 2011. Not surprisingly, Mahbubani strongly rejects most—though not all—of the arguments made in favor of this false economy, by pointing to the negative impact of these funding trends on agencies such as the World Health Organization. While he notes the rise in additional supplementary funds to replace some of these cuts, he interprets these ad hoc donations as a means by which Western donors can support their favorite programs, and not necessarily the ones that are most urgent or do most for global health. He is also skeptical of “market multilateralism,” whereby private funding is used to fill some of the gaps, which lessens the currency of global public goods.

Exploring how to overcome these short-run irrationalities, Mahbubani identifies seven “blockages” that hold back global action: global vs. national interests; the West vs. “the rest”; the United States vs. China; an expanding China vs. a shrinking world; Islam vs. “the rest”; global environment vs. global consumer; and governments vs. civil society. His analysis of these challenges, and of what he describes as the risks of geopolitics derailing convergence, are filled with examples and insights—but also with loose ends and overgeneralizations. Readers at odds with Mahbubani’s optimistic forecast will find lots to disagree with. But nitpicking over the details or the ambitious direction of his argument would, to my mind, be a mistake. He makes a powerful case for strengthening global governance, which, given his considerable international experience, cannot simply be dismissed as idealistic hopes without logic or foundation.

In his last two chapters, Mahbubani offers ideas on how to translate his vision into action. A stronger United Nations is central to them all. His proposals for the UN Security Council—which he believes should expand its membership to 21 states, including a new category of semi-permanent members—are particularly interesting because he gives careful attention to the reasons that different groups of countries might have in supporting or opposing the arrangements he outlines. Council reform is a graveyard of proposals, yet Mahbubani’s are worth a careful read as he blends his ideal scenario with shrewd analysis of possible reform incentives.

Mahbubani concludes by revealing what he calls a “dirty little secret”: Global institutions today are weak by design, not by default. He argues that this has long been a Western strategy, led by the United States, and that even during the cold war, Moscow and Washington, despite disagreeing on practically everything else, actively conspired to limit the influence and leadership of the United Nations. But today, he argues, such an approach no longer serves Western interests. With just 12 percent of the world’s population and a declining share of economic and military power, the West’s “long-term geopolitical interests will quite naturally switch from trying to preserve Western ‘dominance’ to trying to put in long-term safeguards to protect [its] ‘minority’ position” (p. 224). And this means strengthening the rule of law and the institutions that promote it.

It is a powerful challenge, well worth pondering. As a European, I wish Mahbubani had said more about the need for changes of perspectives and strategy not only in the West but in other parts of the world, especially in China, India, and among the main and emerging powers of the South and the East. It was largely the West that created the United Nations and the Bretton Woods institutions at the end of the Second World War. But if global institutions are to be strengthened, it will require new thinking and bolder initiatives focused on meeting long-run challenges among the up-and-coming powers as well as those with waning influence.

Mahbubani’s final chapter returns to his theme that the traditional units of old global and political order, including the “veritable nation-state,” are proving less and less useful in managing global changes. This is a challenge facing every country of the world—its people and its political leaders. Mahbubani argues for strengthening the United Nations and building on it to create a range of effective global institutions; shifting resources from anachronistic military (especially nuclear) budgets to peaceful measures of global governance; and introducing the principle of meritocracy under which the heads of all multilateral institutions would be chosen by picking the strongest possible candidates. But above all, he argues for a shift in public and political thinking, and the development of a global ethic, because “in the next few decades we will increasingly realize that our village is a world and not that our world is a village” (p. 259).

CONCLUSIONS

Economies in all parts of the world are operating at far below capacity, in human as well as in economic terms. Millions of people are suffering from low and often declining incomes, and there are high levels of unemployment all over the globe, especially among young people under the age of twenty-five. Inequalities are rising at an unprecedented rate in most regions of the world, and major risks like climate change are being met with only feeble action. Though national policies are in large part to blame, no country is an island unto itself. Stronger initiatives of global governance are urgently needed to provide the opportunities and incentives for more positive national action.

Each of these three books underlines the predicaments and challenges of global governance today. Globalization proceeds apace, but politics and policies run along well-worn national tracks, as if there was no one-world logic and foreign affairs could reasonably concentrate on the protection of security and sovereignty. Bold thinking and global vision are urgently needed, as they have been at crucial points over the past 200 years—something that Mark Mazower brilliantly makes clear. With global governance manifestly weak and insufficient in the face of ever growing global risks, leaders around the world should be losing sleep over such weakness and inaction, as Ian Goldin explains in his wake-up call. The logic of one world calls for a new vision, new ideas, and new structures for global leadership—as Kishore Mahbubani sets out. All three books need to be read, but Mahbubani’s deserves to be read twice, for the breadth of its perspectives, the specifics of its proposals, and its Asian “can-do” optimism that the rest of the world so desperately needs.

More in this issue

Fall 2014 (28.3) • Essay

Who Are Atrocity’s “Real” Perpetrators, Who Its “True” Victims and Beneficiaries?

Modern law’s response to mass atrocities vacillates equivocally in how it understands the dramatis personae to these expansive tragedies, at once extraordinary and ubiquitous.

Fall 2014 (28.3) • Review

The Confidence Trap: A History of Democracy in Crisis from World War I to the Present by David Runciman

This book provides a clear and plausible articulation of democracy’s central dilemma, paired with a far less definite treatment of its implications for the ...

Fall 2014 (28.3) • Essay

A "Natural" Proposal for Addressing Climate Change

One of the fundamental challenges of climate change is that we contribute to it increment by increment, and experience it increment by increment after a ...