The collective target in the Paris Agreement on climate change is bold—countries together pledge to hold the global temperature rise to “well below” 2 degrees Celsius while “pursuing efforts” to keep the rise under 1.5 degrees Celsius.[1. Paris Agreement, (Annex to Decision 1/CP.21, FCCC/CP/2015/10/Add.1) December 12, 2015. Article 2.1.] However, the hallmark of the Paris Agreement is the control given to countries to determine for themselves what is a fair and ambitious contribution to the overall effort.[2. Nicholas Chan, “Climate Contributions and the Paris Agreement: Fairness and Equity in a Bottom-Up Architecture,” Ethics & International Affairs 30, no. 3 (2016).] This bottom-up element of the treaty has led to a substantial mismatch between the sum of individual countries’ proposed emissions cuts (Nationally Determined Contributions, or NDCs), and the total drop in emissions needed to meet the bold target agreed upon at Paris. A prominent review predicts that the aggregate effect of countries’ fully implemented NDCs would lead to a 50 percent chance of a 2.7 degrees Celsius rise by 2100.[3. Climate Action Tracker, “Effects of Current Pledges and Policies on Global Temperature,” December 7, 2015, http://climateactiontracker.org/global.html.] This mismatch between countries’ individual mitigation commitments and the overall goal is known as the “ambition gap.”

For countries to close the ambition gap, powerful state actors will need to recognize that they have significant incentives to substantially upscale their planned contributions to the overall effort. Reputational concerns on the global stage must form a large part of such incentives. Of course home-grown political pressure on governments provides one form of incentive, but countries also likely change their behavior when elite decision-makers and bureaucrats judge themselves against their peers in other countries. Moreover, states as a whole seek the reputational benefits of being a cooperative actor, such as desirable membership in international groups.[4. For an insightful take on this, see Judith Kelly and Beth Simmons, “Politics by Number: Indicators as Social Pressure in International Relations,” American Journal of Political Science 59, no. 1 (2015).]

One of the missing elements in the Paris Agreement is a formal mechanism by which such reputational effects can be generated and amplified, a mechanism analogous to, for example, the Universal Periodic Review in the international human rights legal regime. While the Paris Agreement provides a basic expectation on countries to submit increasingly ambitious NDCs every five years, there is no forum in the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) through which the ambition of countries’ NDCs can be directly compared.

Plenary session of COP21. Photo credit: COP Paris

Plenary session of COP21. Photo credit: COP Paris

While several NGOs put forward reviews of the adequacy of countries’ NDCs before the Paris summit, I argue below that these reviews falter on one or more key criteria. By contrast, I suggest an NGO review to cluster countries into appropriate groups and rank their climate ambition within such clusters. This, I argue, would be a welcome addition to the NDC process and may better serve the task of closing the ambition gap through reputational incentives.

The Difficult Tasks of a Review

Why is a review process necessary? Why can’t any interested party compare and assess the ambition of individual NDCs directly? Two barriers in particular prevent an easy comparison of the adequacy of ambition in NDCs: the ambiguity of what constitutes a fair share of the climate effort under the UNFCCC, and the diversity of kinds of targets in NDCs.

The Ambiguity of Fairness in the UNFCCC

Like most environmental treaties of the last few decades, the UNFCCC embodies differential treatment among countries. Countries agreed in 1992 that measures to combat climate change would be taken “on the basis of equity” and “in accordance with their common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities” (CBDR-RC).[5. United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (FCC/INFORMAL/84/Rev.1). Article 3.1. The Paris Agreement updated CBDR-RC by adding the qualifier “in light of national circumstances” (Paris Agreement: Preamble, Article 2, Article 4).] However, since there is little agreement on the relevant criteria for differentiation among countries, there is no way within the UNFCCC to translate the concept of CBDR-RC to any specific formula of burden-sharing. Since the task of exposing leaders and laggards requires some progress on the normative step of identifying which countries are meeting or failing to meet their fair share, an effective review of NDCs faces the equity task—it must adequately operationalize the vague UNFCCC equity principles. (In practical terms, this means that existing reviews express fairness not as one specific target, but as a range of emissions for each country.) But even if the UNFCCC equity principles were clear and uncontroversial, a review would still be needed in comparing countries’ NDCs with one another, since the content of NDCs are not easy to compare in their raw form, nor are they likely to be in the future.

Form of NDCs

The climate march in London on Sep. 21, 2014. Photo credit: Garry Knight

The climate march in London on Sep. 21, 2014. Photo credit: Garry Knight

Countries at Paris could only agree upon the roughest of guidelines for NDCs. The only mandatory element is some kind of mitigation component, and even that is flexible in form. The Paris Decision only states that NDCs may include “as appropriate, inter alia… a base year... scope… planning… assumptions….”[6. Paris Decision (1/CP.21): para. 27.] Countries have capitalized on the flexibility they have been granted in the form of their pledges by portraying their substantive effort in the best light possible. So far, states have expressed five different types of targets in their NDCs, from descriptions of actions to be taken (e.g. Antigua and Barbados), peaking years (e.g. Pakistan), carbon intensity of GDP (e.g. Singapore), reductions from business as usual (e.g. Oman), or reductions from a particular base year (e.g. USA).[7. UNFCCC, “INDCs as Communicated by Parties,” http://www4.unfccc.int/submissions/indc/Submission%20Pages/submissions.aspx. See also the collations of INDCs: Climate Policy Observer, “INDCs,” http://climateobserver.org/open-and-shut/indc/ and World Resources Institute, “CAIT INDC Detailed View,” http://cait.wri.org/indc/profile.]

Even when countries choose a similar type of target, each target still needs significant analysis to be converted into a comparable measure of ambition.[8. Joseph Aldy, William Pizer, and Keigo Akimoto, “Comparing Emissions Mitigation Efforts across Countries,” Climate Policy 2016, 1-15.] For example, the 32 countries that have expressed reductions from base years have chosen 14 different base years between them, spread between 1990 and 2025.[9. Ibid.] Those that set reductions from business as usual or of GDP intensity require calculation of the counterfactual “business as usual” baseline many years ahead. In sum, comparing the emissions cuts represented even in NDCs with similar templates is not easy, but it is necessary. Since the reputational incentives pushing a country to submit an ambitious NDC will depend on the possible comparison to other countries’ plans, NDCs that are hard to compare reduce the opportunity for effective pressure towards fair burden-sharing. Thus as well as the equity task, would-be reviewers of NDCs face the harmonization task—to provide modelling to compare the relative levels of ambition among heterogenous NDCs.

Simplicity, Global Credibility, and Granularity

With a sense of both the necessity and difficulty of conducting a review of individual ambition in clear view, we are in a position to consider what key qualities are needed in an effective review of individual ambition. I suggest three: global credibility, simplicity, and granularity. Credibility is the sine qua non for a review of ambition: for a review to be more than just another political statement about the relative climate ambition of different countries, its interpretation of the equity principles and its method of harmonization must be acceptable to a wide range of actors. Without global credibility, reputational effects from a review will remain weak. Simplicity, as it strips away uncertainty to tell a coherent narrative about a country’s endeavors, is also an important feature. A complex, hard to understand rating of a country’s ambition will be unlikely to be picked up by the media, or if it is, unlikely to be widely diffused. Finally, the granularity of the ratings is another element that may be especially important in a review of NDCs. Granularity refers to the level of precision the review gives to ratings or rankings of different countries’ ambition. It relates to simplicity, but does not directly oppose it. A rank ordering, for instance, could be both granular and simple.

That said, reviews may try to increase simplicity and credibility by reducing granularity. Giving a very coarse-grained rating of country’s individual ambition (for example by placing each country in one of three tiers) might eliminate the need for highly exact quantification of states’ contributions. Moreover, because the methodology of precise calculations can be controversial, opting for simplicity may also enhance credibility. On the other hand, coarse-grained reviews have some pitfalls. Because raising individual ambition is difficult, countries falling in the middle or bottom part of a tier may have little hope of ever reaching through into a higher tier, so any reputational incentives that a review creates may be redundant. Conversely, knowledge of the reviewer’s boundary between tiers may cause borderline countries to “game” the system, making their NDC just ambitious enough to reach a higher tier. Also, a very coarse-grained review could just as easily reduce credibility if the method of boundary-placement is not transparent and understandable to viewers. An ideal review would retain granularity while producing a final output that would be simple, yet uncontroversial enough to be globally credible.

Actors

Central to the question of credibility is who performs the review. Several candidates for reviewers are unsuitable from the outset. Since a review requires a concerted analytical effort of many hands, a single individual could not produce it. Moreover, it is not likely that a single individual could attract substantial attention to his or her review. National governments acting unilaterally cannot be globally credible judges, and at the COP-20 negotiations, they rejected the prospect of playing that role together in concert.[10. See Harro Van Asselt, Håkon Sælen, and Pieter Pauw, Assessment and Review under a 2015 Climate Change Agreement, (Nordic Council of Ministers) (2015) and Donald Brown, “Missed Opportunity in Lima: Creating a Process for Examining Equity Considerations in the Formulation of INDCs,” Ethics, Policy & Environment 18 no. 2, (2015).] In light of all this, I suggest an effective review could be best produced by a third-party, research-focused non-governmental organization or group of organizations that represent a range of global perspectives in their outlook and origin.[11. Researchers and independent observers in the UNFCCC system are organised by the Secretariat into the RINGO (Research and Independent NGOs) constituency. A RINGO-led review might mobilize the requisite expertise and begin with considerable credibility, given the carefully neutral stance of most organisations within the constituency.]

Current Reviews of NDCs

Having outlined the need for, and several constraints upon, an effective review of individual ambition, it is important to evaluate the current reviews created by NGOs during the lead-up to the Paris summit last year. So far there are only two reviews—the Civil Society Review and Climate Action Tracker—that assess the fairness of countries’ NDCs in particular.[12. The reviews can be found at www.civilsocietyreview.org and http://climateactiontracker.org/countries.html. At that stage, NDCs were known as Intended NDCs, or INDCs. A country’s current INDC becomes an NDC after it ratifies the Paris Agreement.] The standard approach in making such reviews is to determine three things:

an overall goal for global emissions by 2030, the range of emissions for each country that could represent a fair share of that global budget, and how well a country’s proposed emissions targets compare to that fair range. While such approaches make sense theoretically, the Civil Society Review and Climate Action Tracker’s reviews make unacceptable sacrifices of credibility, simplicity, and granularity. I briefly assess these reviews below.

Civil Society Review

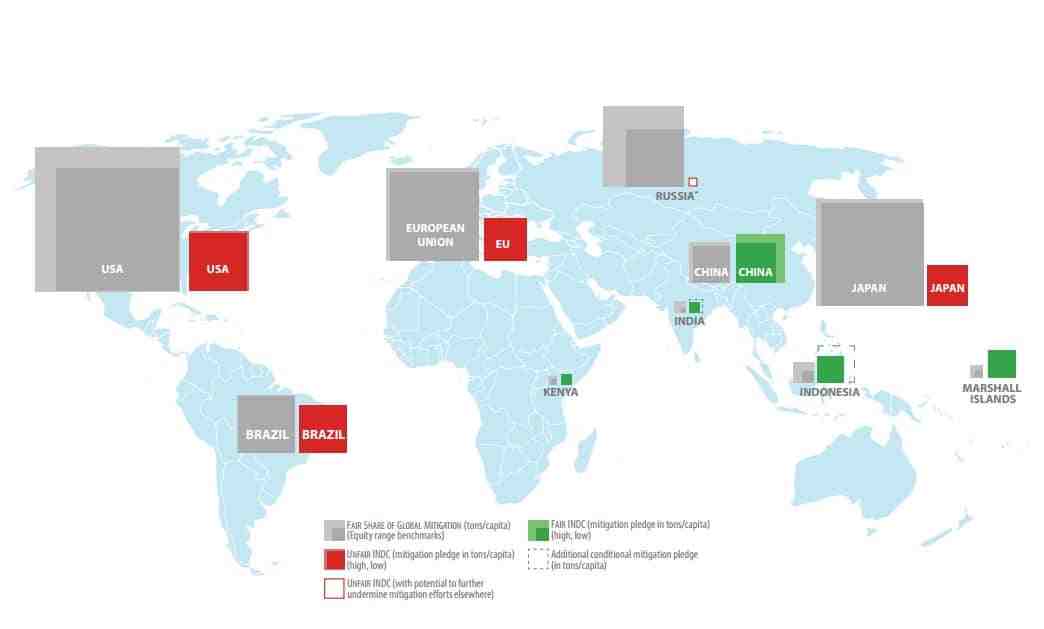

Civil Society Review's assessment of INDCs, from their November 2015 report.

Civil Society Review's assessment of INDCs, from their November 2015 report.

A group of prominent development and environmental NGOs released the Civil Society Review of NDCs just before the Paris Conference last year. The members of the group negotiated between themselves which inputs should represent responsibility and capability in the (independent) Climate Equity Reference Calculator. The Calculator then generated an “equity range” of fair shares of emissions for major developing and developed countries, which was then compared the emissions projections in the countries’ NDCs. The Civil Society Review thus provides a fine-grained output in terms of relatively precise targets for each country, yet the end result also turns out to be simple enough—it is almost solely the developed Western countries that need to close the ambition gap. However, its provenance in a group of NGOs that historically have often been highly critical of developed countries’ positions in international affairs will reduce the review’s global credibility, particularly among the decision-making elite in those very countries that it calls to action.

The Civil Society Review’s methodology further reduces its global credibility. The review calculates what would make a fair contribution by counting only estimated personal incomes above a $7,500 threshold towards the “capability” element of CBDR-RC, and only emissions associated with income above that level towards the “responsibility” element. This means that the methodology shifts more of the burden onto developed countries, where a much higher proportion of the population has an income above the threshold. In a milieu that typically designates two dollars per day as the benchmark for global poverty, increasing the threshold for responsibility and capability by an order of magnitude risks making the Civil Society Review seem partisan in the eyes of those very countries it calls out as laggards.[13. At the official launch of the Civil Society Review during the APA 2-11 at Bonn, Germany, October 19, 2015, representatives of developed countries were largely absent. Developed countries ignored the review in their press conferences and did not discuss them at any length in the plenary.]

Climate Action Tracker

The weakness of the other major NGO review of NDCs lies not so much in its credibility, but in its coarse-grained output. The Climate Action Tracker (CAT) collates the results of around fifty peer-reviewed models of burden sharing along different criteria, removing extreme outliers for each country. This methodology improves the review’s credibility, but because of the wide variety of approaches among the peer-reviewed models, only a very broad “fair emissions range” can be given for each country. The review then splits this fair range into two sub-ranges, giving four possible final positions for each country: inadequate (for emissions above the highest bound of the fair emissions range), medium (for emissions in the upper two-thirds of the range), adequate (for emissions in the lower third of the range), and the currently empty role model position (for emissions below the lowest bound of the fair emissions range). Such a coarse grain may cloud the incentives of countries to raise their ambition. If relevant decision-makers doubt they can substantially improve on their last CAT rating, they have little incentive to significantly raise their ambition in subsequent submissions of NDCs.

![]() Climate Action Tracker's four ranking categories. Full ratings available here.

Climate Action Tracker's four ranking categories. Full ratings available here.

Furthermore, despite its cautious indeterminacy, CAT may also lack global credibility. First, it relies on peer-reviewed literature, mostly from the developed countries (and thus arguably biased against developing countries), to undertake the equity task. Second, although the method of selecting the thresholds between each range and subrange is publically available, it is nevertheless technical enough that it requires many viewers to put faith in the methodology of the reviewer.

Cluster Relative Rankings

Despite their weaknesses, the Civil Society Review and the Climate Action Tracker review are excellent tools for the comparison of NDCs by stakeholders and should be continued and refined. However, in order for NDC reviews to have a strong impact on countries’ ambition, more actors must implement new forms of reviews. Perhaps, instead of trying to measure the fairness of each country’s NDC as the above reviews do, some NGO reviews should try to fairly measure them.

In practice, one way to do this would be to create a broad-brush division of countries into appropriate clusters along CBDR-RC lines, and then ranking countries within their clusters according to the ambition in their NDCs. This is broadly the practice suggested in recent papers by Joseph Aldy and co-authors,[14. Joseph Aldy, “Evaluating Mitigation Effort: Tools and Institutions for Assessing Nationally Determined Contributions,” Harvard Projects on Climate Agreements Discussion Paper (2015), and Aldy et al. “Comparing Emissions Mitigation Efforts."] but as yet no organization has carried it to fruition. As mentioned above, such a cluster-based review would focus primarily on undertaking the harmonization task thoroughly. Prioritizing harmonization would allow the review to minimize the equity task, reducing the risk that its particular interpretation of CBDR-RC will cause it to lose global credibility.

How might this work? One way would be to group countries into clusters along several metrics of capability, including standard metrics of economic ability and human development, as well as natural resources available for renewable energy. Perhaps the number of clusters should not be chosen in advance, but determined using data analysis to find appropriate clusters of countries with similar levels of capability. Within clusters, NDCs could then be translated into the most appropriate or common metric in the cluster, such as the pledged change in emissions per capita, or per unit of projected GDP. Such a rating would be both determinate and simple: each country will have a given rank within a cluster. And focusing on rankings within each cluster lessens the impact of heterogeneity in the format of NDCs, and thus reduces the amount of potentially contentious analysis needed to harmonize different targets.

Of course, clustering countries according to capability engages only part of the equity task. Historical responsibility would also have to be respected to some degree to make the approach credible to those who stress the normative importance of historical emissions. One way might be to factor historical emissions into the calculation that clusters the countries. However, any method for determining the significance and measurement of historic responsibility could be called into question, conversely damaging the credibility of the review. To avoid controversial questions about the precise significance of historical responsibility, a review could split the highest-capability cluster (or clusters) into two sections—those containing Annex 1 “developed countries” that had, when the UNFCCC was signed “the largest share of historical… emissions of greenhouse gases”[15. These words are from the Preamble of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (1992).] and the rest—the non-Annex countries. Since countries would be given a rank within each cluster, the review is granular, and a country might jump several places above its peers by submitting a more ambitious NDC. At the same time, a rank ordering is simple and conveys information quickly and effectively.

Smoke Stack from Sugar Factory in Belle Glade Florida. Photo credit Kim Seng.

Smoke Stack from Sugar Factory in Belle Glade Florida. Photo credit Kim Seng.

Meeting objections

At this point one might worry that a cluster-relative review would revive and breathe life into what became one of the most contentious aspects of the UNFCCC—“firewalls” between groups of countries. However, that objection ignores the ability of the reviewing organization to create definitive, transparent criteria to allow countries to switch between clusters, something the UNFCCC sorely lacks.

A more serious objection is that, by focusing on incentivizing fair burden-sharing within clusters of similarly-placed countries, fairness between clusters of countries will suffer. It is true that such a review could not judge whether one cluster (the richest, for example) were shirking its responsibility compared to other clusters. Given the power asymmetries in world affairs, this may equate to rich countries leaving the burden of climate change to the middle-income countries, without suffering negative reputational effects.

It is true that the cluster-based approach is unable to serve as a direct assessment of the fairness between such clusters of countries. But three things must be said to ameliorate this apparent weakness. First, the lack of judgement about groups of countries may actually be helpful rather than harmful. Conflict between developed and developing countries and led the UNFCCC into an effective stalemate for two decades, and self-differentiation offers a way out of that dynamic. A review process that does not take sides on the old conflicts between typical classes of countries might avoid those tensions that led to deadlock in the negotiations. Second, we should note that a review of NDCs is not the only, or even the best forum in which to make the case for whole groups of countries to take on more responsibility for climate change. Civil society can perhaps best agitate for fairness between the clusters along traditional channels of lobbying and awareness-raising, outside of a review of NDCs with its particular constraints of the harmonization and equity tasks. Third, we may think that the greatest moral threat of climate change is that it sets up a “tyranny of the contemporary” in which the present generation unjustly dominates the most vulnerable of future generations.[16. Stephen Gardiner “A Perfect Moral Storm: Climate Change, Intergenerational Ethics and the Problem of Moral Corruption,” Environmental Values 15 no. 3 (2006).] If so, we may accept some potential unfairness between some groups as a regrettable consequence of prioritizing just behavior from the current generation as a whole towards future people.

A final worry could be that focusing attention on measuring the relative ambition of NDCs within clusters gives us no information about how well the world as a whole is doing to meet the global goal of keeping the temperature rise well below 2 degrees Celsius. But the task of assessing collective progress towards closing the ambition gap is politically less fraught than assessing individual ambition; countries showed great willingness at Paris to be guided by a collective assessment under the auspices of the UNFCCC. The Paris Agreement holds that every five years, the parties will perform a “global stocktake” to “assess the collective progress” towards achieving, among other things, the global temperature goal.[17. Paris Agreement, Article 14.1] A review of individual ambition thus need not duplicate this function.

The task of reviewing NDCs represents a vital opportunity for NGOs to engage meaningfully in combatting climate change by generating reputational effects and spurring countries to more ambitious action. Indeed, some organizations have already taken up the task. The two existing reviews achieve simplicity in their final outputs, but often at the cost of granularity and global credibility. One way for new NDC reviews to address this shortcoming is to invert the approach—to focus on the harmonization task first—and perform the bare minimum on the equity task to remain faithful to the most basic understandings of CBDR-RC. While all reviews will have their flaws, and a multitude of reviews will be necessary to comprehensively assess fair burden-sharing, a cluster-relative review may be one of best ways to push countries further towards closing the ambition gap.