In October 2017, global diplomacy took a turn toward the contemplative. A man the Guardian newspaper calls the “godfather of modern mindfulness,” Jon Kabat-Zinn, sat down with international politicians in a secular meditation session. The meditating dignitaries from countries including Israel, Sri Lanka, and Sweden gathered in the UK House of Commons and were led in meditations designed to enhance their awareness and tap into their compassion. Also present at this meeting was U.S. Congressman Tim Ryan, who wrote a book on mindfulness and is a possible 2020 presidential candidate.

This meeting marks the early forays of the global mindfulness trend into the realm of international diplomacy. With proven benefits to mental health and wellbeing, mindfulness has caught on like fire in the West. It has been adapted to a variety of cultures and settings, permeating social and economic systems from healthcare to education to business. A practice that originated thousands of years ago from the early teachings of Buddha has become a modern phenomenon.

The term “mindfulness” refers to a process in which one is attendant to the present moment—to one’s thoughts, feelings, bodily sensations, and surroundings, regarding them with a sense of curiosity and kindness. Kabat-Zinn describes mindfulness as “paying attention, on purpose, in the present moment, and non-judgmentally.” Mindfulness can be cultivated in meditation, often by focusing on the breath as an anchor for attention (a dedicated practice); or in everyday activities, by noticing when the mind is wandering and coming back to the present moment (an integrated practice). Mindfulness, and all forms of meditation, trains the mind to hold attention to a desired end. The alternative—the default way the mind works—is sometimes called the “monkey mind” because of the human tendency to ruminate about the past or project into the future. Such a wandering mind can result in focusing on situations in unconstructive ways, often leading to depression, anxiety, or strained relationships.

The benefits of mindfulness have become so widely reported that in any given week media headlines feature reports of this or that group meditating, from prisoners to school children to CEOs of multinational corporations. Likewise, new studies are published at breakneck speed that make a variety of claims about mindfulness and its impact on attention span, immunity, aging, and stress management, among many others. Researchers Daniel Goleman and Richard Davidson note in their 2017 book Altered Traits that when they began studying mindfulness in the 1970s, there were merely a few studies dedicated to meditation. Today, they report, there are close to 7,000 studies and counting. While Goleman writes in the Harvard Business Review that many of the studies are not as rigorous as they would like, some benefits stand up to intense scrutiny, particularly in the areas of focus, stress, memory, and good citizenship.

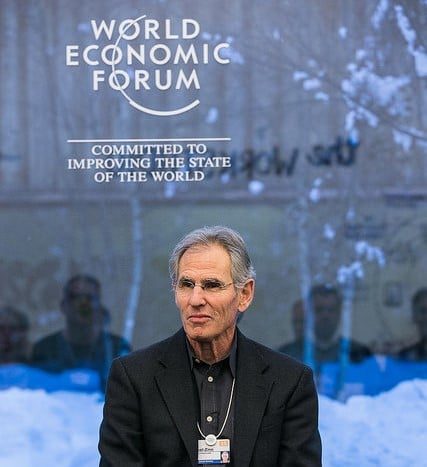

Jon Kabat-Zinn at the Annual Meeting 2015 of the World Economic Forum in Davos, January 23, 2015.

Jon Kabat-Zinn at the Annual Meeting 2015 of the World Economic Forum in Davos, January 23, 2015.

The meteoric rise of mindfulness is often credited to Kabat-Zinn and his eight-week course, Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction (MBSR), first taught at the University of Massachusetts in 1979. Today, MBSR is taught at clinics and hospitals around the world, and more than 24,000 people have taken the course just at the University of Massachusetts. Furthermore, it is one of the most frequently studied forms of meditation. A quick search on Google Scholar yields more than 83,000 references and more than 8,400 in 2017. Studies on MBSR have shown a range of benefits for participants, including lowered stress response, improved focus, decreased social anxiety, and even attenuated feelings of loneliness. Thanks to MBSR and other meditation practices, people everywhere have accepted the notion that the mind holds the key to changing their lives. For those concerned about matters of global policy—or the fate of our planet—the next question becomes: does the mind also hold the key to changing the world?

Some people are already betting on that. Chade-Meng Tan, a former software engineer at Google, founded the company’s mindfulness program, Search Inside Yourself, in 2007. The course has been taken by thousands of so-called Googlers and is now taught in major companies worldwide through a separate organization, the Search Inside Yourself Leadership Institute. Tan also wrote the eponymous Search Inside Yourself book. He opens the book by discussing how the course has improved the lives of his fellow Google employees, but he ends it by revealing that his true motivation is world peace. “Like many others wiser than me, I believe world peace can and must be created from the inside out.” (In full disclosure, I am currently a teacher-in-training with the Search Inside Yourself Leadership Institute).

Yet while mindfulness has soared in popularity at companies like Google and has been successfully adapted in schools, hospitals, and even Parliaments, it has not yet been fully explored as an instrument to bring greater understanding among nations. This means that a sizable opportunity exists to apply mindfulness in diplomatic settings, especially given that some conflicts have endured for decades. How exactly can this be done? By borrowing and adapting what has worked elsewhere. Below are some examples of how to incorporate mindfulness into a diplomatic setting:

- Opening meetings with a pause. Because each of us brings a range of thoughts, feelings, and distractions into any new situation, opening with a pause allows meeting participants to fully arrive in the room and to let go of whatever else is calling for our attention. A collective pause puts everyone on the same page.

- Setting an intention for the meeting. While this can be personal, perhaps formulated in the opening pause, it can also be a collective opportunity to focus on the shared objective of the meeting, a reminder that ultimately the goal is a solution that works for everyone.

- Practicing mindful listening. Too often we do not genuinely hear what a counterpart is saying, because we are preparing our own response, judging the contents of what we hear, or simply thinking about something else. Mindful listening means focusing fully on what the speaker is saying, noticing when the mind has wandered, and gently returning attention back to the speaker. In addition to ensuring each speaker feels heard, mindful listening can create extra space for a thoughtful response.

- Becoming aware of how “stories” can impede progress. One of the key deterrents of progress in international diplomacy is the inability to move past perceived wrongs. Through mindfulness, we become aware of how the mind tends to cling to repeated narratives, even unhelpful ones. These stories then become so entrenched in our identities as individuals and nations that it becomes hard to transcend them. With mindfulness, we can learn to focus on the issues right in front of us, as opposed to past grievances that may be thwarting the greater good.

- Focusing on compassion. While a mindfulness practice is primarily meant to sharpen focus, some meditations specifically enhance compassion, and thus decrease the sense of “otherness” that so often hampers diplomacy goals. Goleman and Davidson report that with compassion training, “reductions in usually intractable unconscious bias can emerge after just sixteen hours.”

- Employing mediators who are trained in mindfulness practices and can guide participants in all the above. Neutral parties are often key to reaching any kind of peace agreement, and using nonjudgmental mediators who are skilled in mindfulness can increase the likelihood of success.

As with any new technique, there will be resistance to using mindfulness in a diplomatic setting, and it should not be expected to have uniform success. Some may be skeptical of efforts to introduce mindfulness to international diplomacy. Others may have overly high expectations about what mindfulness can achieve and how fast. Further, international adversaries suffer from a notorious deficit of trust and psychological safety, and for some, the appearance of vulnerability could be too much to bear.

However, none of the above means that we should not pursue mindfulness as a diplomatic tool. One option is to introduce the practice in less contentious situations where it is more likely to yield benefits. Supporters who already have an active practice or are open to trying one can float the idea among counterparts or can advocate for its inclusion. Furthermore, mindfulness can be introduced slowly, perhaps starting just with an opening pause or an exercise in mindful listening, before moving on to other techniques.

The concept of mindful diplomacy might be new to many, but the visionary United Nations Secretary General Dag Hammarskjold was already thinking about it back in the 1950s. In 1957, Hammarskjold oversaw the creation of a meditation room at UN Headquarters “dedicated to silence in the outward sense and stillness in the inner sense.” While the actual room now largely serves as a tourist attraction, the concept behind it is finally catching up with Hammarskjold’s vision as people increasingly turn inward for answers—and increasingly find scientific evidence validating that choice. Studies have shown that compassion and composure, the very traits that can lead to diplomatic success, are learnable skills. But the willingness to explore them and the humility to try something new are paramount. Mindful diplomacy may be the pathway to the progress we seek, and even to peace itself.

Abigail Somma is a former UN speechwriter. She currently offers trainings in both speechwriting and mindfulness meditation, and manages The Mindful Goods, a resource for mindfulness news and information.