On September 13, 2022, Mahsa (Jina) Amini, a young Kurdish woman from the western city of Saqqez, in Iranian Kurdistan, was visiting Tehran with her family when she was stopped by the Gasht-e Ershad (Guidance Patrol), a special unit that enforces Iran’s obligatory Islamic dress codes (hijab) and sex segregation. Iranian women have been creatively defying compulsory veiling for some time by pushing their headscarves back and wearing colorful clothing, but last year, current president Ebrahim Raisi called for stricter enforcement measures. Mahsa Amini was detained and taken in for questioning. Shortly thereafter, she was hospitalized after losing consciousness and died at Kasra Hospital several days later. The authorities attributed her death to underlying health conditions, but her family denied that she had any.1

The day after her death was announced, protests broke out in cities across the country, and are now ongoing. The nationwide uprising has been called a women-led revolution, unprecedented not only in Iran but across the world. It has been joined by countless men of all ages, social classes, and ethnicities in a bold show of shared anger over police brutality, the unjust targeting of the young Kurdish woman, and the Islamic regime’s authoritarian rule. These grievances are inscribed in the slogan heard across the country: “Woman, Life, Liberty” (Zan, Zendegi, Azadi).

The forms of collective action across the country have been dramatic: young women burning their headscarves and some cutting their hair in a display of mourning for Mahsa; others defacing images of clerical leaders; yet others defiantly walking about without hijab. From the start, young men joined the protests, and eventually began to throw stones at police and more recently attack police stations and vehicles. To date, the protests have been “horizontal,” that is, leaderless, often spontaneous, and without a defined program. The scale and persistence of the protests, however, raises the question: Is this the end of the road for the Islamic Republic?

These grievances are inscribed in the slogan heard across the country: “Woman, Life, Liberty” (Zan, Zendegi, Azadi)

Some historical context is important. Though the ongoing protests are distinctive and unprecedented in many ways, they are part of a longstanding cycle of dissent and collective action—much of which has been organized by women—that has been directed at the Islamic Republic since its founding. Women, for instance, organized the very first protest following the Islamic Revolution, gathering in Tehran on March 8, 1979, a day after Ayatollah Khomeini called on women to observe hijab. The 1980s were characterized by intense ideological pressures, the war with Iraq, and multiple executions at the end of the decade, just before Khomeini’s death.2 The 1990s saw some relaxation of restrictions on women’s dress and participation in society, the introduction of access to satellite TV and then the Internet, growing female university enrollments, and increased international travel. The reformist era and emergence of an incipient civil society helped revive the student movement in the summer of 1999. However, the large student protests over the closure of a reformist newspaper were harshly repressed, as were the feminist campaigns in the early 2000s demanding legal and policy changes, such as the ratification of the UN’s Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women.3 Young and middle-class women were also a large presence in the 2009 Green Protests, which targeted what was seen as a rigged presidential election. Economic difficulties, generated by tough U.S. sanctions, the onset of austerities, and government mismanagement, were at the center of the protest wave of late 2017 through early 2018 and again in November 2019, which were dominated by working-class and lower-income men across the country.

The Role of Europe and the United States

That the Iranian state has been oppressive toward so many of its citizens, and that women face codified discrimination, is beyond dispute. In the wake of the recent protests, some in the diaspora have called for Western intervention to help enact regime change. This would be a mistake, and not only because of the wreckage left behind by Western interventions in Afghanistan in 2001, Iraq in 2003, and Libya in 2011. Over the decades and up to the present, the U.S. has not been an innocent bystander in Iran’s affairs and European countries have been less than helpful to the Iranian people. The 1953 U.K./U.S. coup d’état against Premier Mossadegh’s liberal nationalist government looms large in the national historical memory. In this century, the Bush Administration designated Iran part of the “axis of evil,” despite widespread Iranian expressions of sympathy after the 9/11 attacks and the reformist government of President Khatami’s offer to help track down al-Qaeda jihadis.4 The reformists lost to hardliners in the next presidential and parliamentary elections. As a result, many Iranians are skeptical of Western meddling and posturing. And then there are the economic sanctions and the fate of the 2015 Iran nuclear agreement (the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, or JCPOA).

Over the decades and up to the present, the U.S. has not been an innocent bystander in Iran’s affairs and European countries have been less than helpful to the Iranian people.

After Iran’s uranium enrichment program raised alarms in Western capitals, steps were taken to ensure that a nuclear weapon was not in the making. The JCPOA was an international agreement concluded by the governments of Iran and the United States, the Security Council’s P5, and the European Union. It raised hopes among many Iranians that the lifting of sanctions and normalization of relations with Europe and North America would relieve the high youth unemployment and low female labor force participation through trade, tourism, and investments.5 But just three years later, the Trump administration withdrew from the agreement and then instigated even more punitive economic and financial sanctions, blocking the central bank’s access to SWIFT. Initially, the Europeans offered a mechanism, the INSTEX, that would enable Iran to carry on trade and finance with European partners. Gradually the Europeans became unwilling to incur the wrath of the Trump administration, leaving Iran to seek new trade partners. Sanctions and commodity price volatility exacerbated inflation and the economy’s stagnation, triggering the aforementioned protests in late 2017/early 2018 and again in late 2019. COVID-19 hit Iran hard, but by that time, many Iranian citizens had come to blame the regime for mismanaging the pandemic and the economy. The government’s 2020 request for a $5 billion loan from the IMF to fight the pandemic and ease its economic burden, Iran’s first loan request in over sixty years, was refused due to U.S. pressure.6

One might be forgiven for wondering how economic sanctions, the abrogation of an international treaty, and loan denial could benefit ordinary Iranian citizens, much less the causes of diplomacy, regional security, and world peace.

Whither the Islamic Republic?

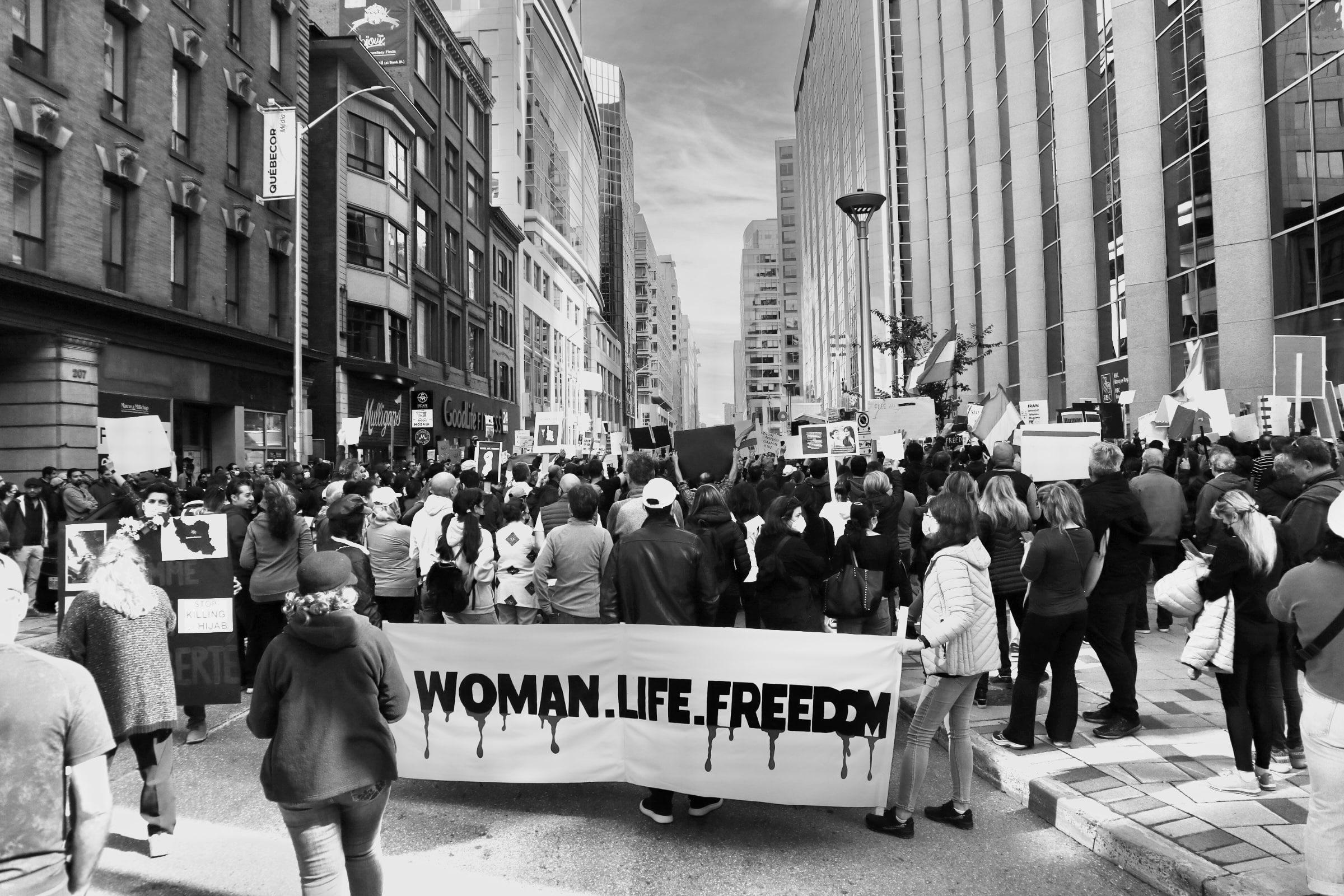

In early 2011, when the Tunisian protests broke out and President Zine al Abidine Ben Ali was forced out, a witty Iranian refrain was, “Tunis tunest, ma natoonesteem.” It is a play on words that means “Tunisia did it, and we couldn’t.” That sentiment has changed. Iran’s protest wave has engulfed all major cities, including the holy cities of Qom and Mashhad, along with the marginalized and securitized region of Sistan and Baluchistan, the southern province of Khuzestan, and Mahsa’s home province of Kurdistan.7 University and high school students are the major social force behind the protests. Most even have the blessing of parents and grandparents, especially those who took part in the protests of previous decades or who quietly opposed the regime’s restrictions but dared not act. The youth also enjoy much global solidarity and support, through rallies, petitions, and open letters, denouncing the Iranian government’s violent crackdown. Tunisian singer Emel Mathlouthi, famous for her songs during the 2011 uprising, dedicated a concert to Mahsa and the youth of Iran, and poignantly sang the well-known Iranian song about love and sympathy, “Soltan-e Ghalbha.” Huge rallies have taken place in Toronto and Berlin, with smaller ones across other cities in Europe and the United States.

Solidarity demonstration in Canada. Photo credit: Taymaz Valley via Flickr

Solidarity demonstration in Canada. Photo credit: Taymaz Valley via Flickr

The protests continue, but sadly so do deaths, injuries, and arrests by the security forces. In late October and into November 2022, the U.S. and European Union imposed new sanctions, this time targeting Iranian officials over the continued crackdown on protesters. The hardliners in power appear unwilling to retreat, admit their faults, or agree to a popular referendum, as such steps could result in the unravelling of the Islamic Republic’s edifice. This is because the protests are no longer exclusively about hijab, as important as that is to the Islamic Republic’s identity.

Though the ongoing protests are distinctive and unprecedented in many ways, they are part of a longstanding cycle of dissent and collective action that has been directed at the Islamic Republic since its founding.

The demands of Iranians inside and outside Iran are now for the collapse of many of the institutions that constitute the nizam-e eslami, or theocratic system, and the velayat-e faqih, or rule of a supreme religious leader; the Guardian Council, which vets candidates for office; the Revolutionary Guard Corps (Sepah) and its civilian militia the Basij; the gasht-e ershad, known in the West as the morality police; the Islamic-based penal code; the family law provisions of the Civil Code; and—perhaps most fundamentally—the Constitution. That so much of the Iranian citizenry now consider the Islamic state illegitimate and beyond reform is a profound political crisis of the regime’s own making.

Despite some criticisms from within the political elite of the regime’s handling of the protests,8 it seems unlikely that Iran’s ruling circles will agree to substantive reforms. If no concessions are forthcoming, how much more force and coercion can be applied? The repressive apparatus under the clerical establishment, notably Sepah and Basij, appear unwavering in their loyalty, but what about the regular armed forces? Could a hypothetical military coup resemble those that took place in Chile and Argentina? Or, more recently, Egypt? One might hope for something closer to the anti-dictatorship uprising in 1974 by Portuguese military officers. How likely is it that Iran’s military would step in to restore stability, secure the borders, and enact at least some of the institutional reforms demanded by protesters? It is difficult to predict the outcome of the women-led protests, which have lacked leadership and strategy and face a still-resilient Islamic state, one that would surely counter any foreign-led military intervention. But what is also certain is that the Iranian people, especially its large youth population, are no longer willing to accept the laws and norms of the Islamic Republic. Thus, even if the current protest cycle retreats under conditions of severe repression, it will surely re-emerge. Educational attainment, digital technologies, the global diffusion of the UN’s women’s rights agenda, and other transnational effects have given rise to new expectations and aspirations, as well as grievances. Meanwhile, the world is watching, waiting to see what unfolds, and hoping for a new dawn.

Valentine M. Moghadam is Professor of Sociology and International Affairs, and former director of the International Affairs Program, at Northeastern University, Boston. Born in Tehran, Iran, Prof. Moghadam studied in Canada and the U.S. In addition to her academic career, Prof. Moghadam has twice been a UN staff member (UNU/WIDER, Helsinki, Finland, 1990-1995; and at UNESCO, Paris, 2004-2006). Her many publications include Modernizing Women: Gender and Social Change in the Middle East (1993; 2003; 2013), Globalization and Social Movements: The Populist Challenge and Democratic Alternatives (2020), and After the Arab Uprisings: Progress and Stagnation in the Middle East and North Africa (2021, with Shamiran Mako). In Fall 2021, Prof. Moghadam was the Kluge Chair, Countries and Cultures of the South, at the U.S. Library of Congress, working on a project entitled “Varieties of Feminism in the Middle East and North Africa.” A recent publication, co-authored with two Kurdistan-based Iranian sociologists, is "Women in Iranian Kurdistan: Patriarchy and the Quest for Empowerment”, Gender & Society, vol. 35, no. 4 (Aug. 2021): 616-642.

- 1 For details on the official report, see Hyder Abbasi, “Mahsa Amini Did Not Die from Blows to Body, Iranian Coroner Says amid Widespread Protests”, NBC News, October 7, 2022, https://www.nbcnews.com/news/world/mahsa-amini-death-iran-morality-police-protests-coroner-report-rcna51169. ↩

- 2 Estimates are that over 3,000 political prisoners were executed between late July and early October 1988, following a border assault by the Iraq-based Iranian Mojahedin organization. Most of those executed were Mojahedin members or supporters, including very young people, but also leftists who had had no role in the armed attack. See Abdorrahman Borumand Foundation Report, “Massacre of Political Prisoners in Iran, 1988” (2010), www.iranrights.org/library/doc118.pdf; and “Iran’s 1988 Mass Executions Evidence & Legal Analysis of “Crimes Against Humanity,” Human Rights Watch, June 8, 2020, https://www.hrw.org/news/2022/06/08/irans-1988-mass-executions. ↩

- 3 V. M. Moghadam, Modernizing Women: Gender and Social Change in the Middle East (Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner Publishers, 2013 [third edition]), esp. pp. 201-207. See also V. M. Moghadam and Fatemeh Haghighatjoo, “Women and Political Leadership in an Authoritarian Context: A Case Study of the Sixth Parliament in the Islamic Republic of Iran,” Politics and Gender, vol. 12 (2016): 168-197. ↩

- 4 See President Khatami’s 2001 CNN interview on the 9/11 attacks, “Iranian President Condemns September 11 Attacks,” CNN, November 12, 2001, https://edition.cnn.com/2001/WORLD/meast/11/12/khatami.interview.cnna/; see also a later analysis, “Iran Gave U.S. Help On Al Qaeda After 9/11,” CBS News, October 7, 2008, https://www.cbsnews.com/news/iran-gave-us-help-on-al-qaeda-after-9-11/. ↩

- 5 An example of a study hopeful that the JCPOA would help strengthen Iran’s tourism sector is Massood Khodadadi, “A New Dawn? The Iran Nuclear Deal and the Future of the Iranian Tourism Industry,” Tourism Management Perspectives, vol. 18 (2016), pp. 6-9. ↩

- 6 See Ian Talley and Benoit Faucon, “U.S. to Block Iran’s Request to IMF for $5 Billion Loan to Fight Coronavirus,” The Wall Street Journal, April 7, 2020, https://www.wsj.com/articles/u-s-to-block-irans-request-to-imf-for-5-billion-loan-to-fight-coronavirus-11586301732 (last accessed November 2022). ↩

- 7 For information on the status and grievances of Kurdish women, see Sahar Shakiba, Omid Ghaderzadeh, and Valentine M. Moghadam, “Women in Iranian Kurdistan: Patriarchy and the Quest for Empowerment,” Gender & Society, vol. 35, no. 4 (Aug. 2021), pp. 616-642. ↩

- 8 A former conservative speaker of Iran’s parliament, Ali Larijani, criticized compulsory veiling and its enforcement; see https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/oct/12/iran-hijab-law-protest-ali-larijani?ICID=ref_fark. ↩